Esquimalt Harbour is only three miles from Victoria with its museums, restaurants and shops, but boaters rarely see this larger harbour as a destination in its own right. Yet with Fisgard Lighthouse and its accompanying Fort Rodd Hill, and Cole Island tucked into the northern segment of the harbour, Canada’s Pacific Coast’s oldest military buildings and grounds beckon boaters.

Leaving Victoria, or on your way west in Juan de Fuca Strait, you turn to starboard just past Duntze Head, and enter the harbour the British Royal Navy made its North Pacific headquarters from 1842 to 1905. It was large enough for sailing ships to enter, wear and drop anchor, yet its surrounding hills offered protection from Juan de Fuca’s strong winds. With a bit of imagination, we can conjure up the ghost of HMS Pandora, the sailing ship that surveyed the harbour in 1842.

According to Barry Gough’s Britannia’s Navy, “ [in 1858] . . . the first of Her Majesty’s ships to anchor [in Esquimalt Harbour] was the fine frigate Constance, mounting 50 guns, and one of the many men-of-war built in Pembroke Yard, Wales.” Gough emphasizes the importance of Esquimalt Harbour in Britain’s quest for “global power and profit.” He writes, “Britain had found its anchor of empire in the North Pacific and from this Canada was to acquire the watchtower on its western shore with tentacles in the high Arctic. . . .”

Today, the first structure we see on our way into Esquimalt Harbour is Fisgard Lighthouse, a National Historic Site. It was constructed on a cluster of islets to guide the naval ships—and us—into the harbour and was the first lighthouse on Canada’s Pacific coast. Its lantern, brought from England by its first keeper, George Davies, was lit daily beginning on November 16, 1860 (Race Rocks’ light began operating on December 26, 1860, six weeks after Fisgard’s). Before the light was automated in 1929, its last keeper, Josiah Gosse, would row to the island several times a day to see if all was well. The frigate HMS Fisgard, herself named after a Welsh town, bestowed her name on the light (her name also lives on in Fisgard Street in the heart of Victoria’s Chinatown).

The 14.6-metre brick tower, painted a stark white for visibility against a darker background, is topped by a red lantern room and unlike most BC lighthouses, is directly connected to the keeper’s residence. Simple brick brackets, called “corbels,” surround the lantern room that both embellish and support the tower’s top. The tidy, brick keeper’s house is painted a vivid scarlet, with white wooden shutters protecting its windows. After anchoring in the harbour, you can easily access the site by dinghy, kayak or paddleboard from the ample beach at the bottom of the complex.

The inside of the keeper’s house gives us a good idea of what his life was like in the 19th century: cold, isolated and spare. We enter by the kitchen with its potbellied stove for cooking, followed by a living room. Wood fireplaces were supposed to heat the home, but their warmth didn’t reach far. One keeper painted the floors in black-and-white squares—poor man’s marble—to mimic the tile floors in Victoria’s mansions. Apparently, he’d asked for rugs, but was told “no carpet can be allowed.”

Keepers had to be married to work on a light. When he left or was unable to operate the light, his wife was expected to serve—but without compensation. Wifely work is also reflected in the wild parsley, likely sowed 100 years ago, that still grows around the dwelling.

From one bedroom upstairs, a green steel circular stair leads to the lantern room; it’s closed to the public as the light continues to serve as a navigational aid.

Fisgard Lighthouse is now connected to the land with a causeway leading to Fort Rodd Hill, which, like the lighthouse, is a National Historic Site managed by Parks Canada (Rodd Hill was named after John Rashleigh Rodd, 1st Lieutenant on HMS Fisgard). The fort, one of a group of defensive positions on Vancouver Island, stands on a rocky bluff overlooking the western side of Esquimalt Harbour and served as a coastal artillery fort from about 1897 to 1956. British troops first staffed the fort; Canadians took over in the early 1900s. The fort includes three gun batteries, underground magazines, guardhouses, barracks and searchlight emplacements.

I walked up the bluff surrounded by bunches of kids. The six-inch “disappearing” guns and their placement fascinated us all—it was the war technology of the day. The guns were sited behind a heavy rock face reinforced by 10 feet of concrete. Lowered behind their parapets by a hydro-pneumatic system, the guns were loaded, then the five-ton barrel was raised above the emplacement ready to shoot. Gunners calculated targets after receiving info from the Depression Range Finder. After a salvo, the artillery sank again into the hollow, lowering their profile. The guns’ emplacements became obsolete by the end of the First World War.

The barracks give a good impression of how the mostly reservist soldiers lived in past times. A sample room is organized and tidy, shows how bedding was carefully folded, and displays uniforms suspended on the wall with their peaked caps on shelves above. Gear to spit-shine shoes is laid out. Eight “casemates” usually shared a room, but when needed, extra troops could swing their hammocks from hooks inserted into the ceiling.

The fortress plotting room is furnished with between-the wars communications equipment supplemented with a tracking board to pinpoint enemy aircraft and ships. In a corridor, the well-protected magazine reveals scores of shells.

Flanked by old artillery guns, the ample grounds where troops trained and paraded, are now an enticing playground for families. You can even camp here in the summer in one of the five oTENTik tents, where up to six persons can sleep.

We all know the old phrase, “keep your powder dry.” Black powder won’t fire if wet, so keeping it dry allowed a gunner to fire a projectile when required. Leaky sailing ships frequently had wet powder aboard, making it unstable and dangerous. Powder, gun cotton, cartridges, shells, mines, rockets and small arms ammunition were all stored on Cole Island from 1859 to 1938. The 0.6-hectare island’s location in the north end of Esquimalt Harbour protected the nearby dockyards from potentially devastating explosions. The island was named after Edmund Picoti Cole, master of HMS Fisgard.

Sixteen buildings once occupied the island, with Royal Marine guards living and working there, maintaining the buildings and growing gardens. But just before the Second World War, Cole Island lost its importance as an ammunition depot and its buildings were abandoned. Jurisdiction over the island shifted several times. The historic structures deteriorated and vandals arrived, spraying graffiti and helping themselves to timbers and bricks. Our rainforest climate caused the vegetation to overgrow much of the island. Building that had once been crucially important like the 1882 Guncotton Store and the 1891 Fuse Tube and Rocket Store disappeared. Now, only four ammunition magazines and one guardhouse remain. They’ve been saved in part because a group of people who live near Esquimalt Harbour formed the Friends of Cole Island and, with local municipalities, began a campaign to stop the destruction of this maritime heritage site. Their advocacy led the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada to list Cole as a National Historic Site in 2006. The Island is now under the protection of the BC Heritage Branch.

Richard Linzey, BC Heritage Branch’s director, has been a decade-long supporter of Cole Island conservation. “It’s a particular gem,” he told me. “I’d worked on military heritage buildings in Britain and was able to offer expertise on the conservation of Cole Island’s brick structures. They resemble the military masonry buildings on the Thames.”

Funding from BC and Parks Canada has rescued the extant buildings. Conservator specialists Gord MacDonald and Ben Gourley, of Heritage Works, design and specify repairs at sites, including the yellow cedar walkways that are constructed exactly like the late 1800s boardwalks. “The Island is evocative and the former ammunition magazines provide excellent opportunities for heritage education,” MacDonald said. “Working with UVic and Royal Roads University, we hold weeklong sessions on Cole. We teach students how to use traditional materials like lime mortar, masonry techniques and big timber repairs. We even brought in a specialist mason from England. The public is welcome when we hold classes. Construction work is ongoing. Our next task is to extend the boardwalks to the guardhouse.”

When you dinghy or paddle up to the island, you’ll come upon two tall brick structures—the ammunition storage buildings—with their feet in the salt chuck. Two Roman arches pierce each façade and sturdy wooden balconies are fixed below the higher arch. Two hefty 60-foot beams, which run the length of each building, stick out above the balconies and can hoist heavy loads into the premises. Below them, you can walk on the rocks at low tide.

On the other side of the islet, a small dock allows for dinghy/canoe/kayak tie-ups. From there, the gangway leads to a brand-new cedar boardwalk. Because of past vandalism, the doors and windows have been fitted with steel barriers and the buildings are no longer open to the public, but do have sight holes to give a glimpse of the hefty timbers inside. Some of the metal doors carry plaques with explanations and photos, with one showing British women stacking shells and ammunition boxes during the Second World War.

Linda Carswell, an ardent Cole Island supporter, was kind enough to show me the buildings’ interior. In your mind’s eye, you could visualize stacks of powder barrels, bales of cotton and shells on the long, knotless floorboards. A few of the artifacts collected include rusted hand-made nails and bricks fired by brickmaker Martin in Leemoor, Devon. I wondered whether these bricks were ordered or brought over as ballast in the Royal Navy ships all the way around Cape Horn.

Volunteers have removed the overgrown and invasive vegetation so that the many curvaceous arbutus trees stand out. Like Fort Rodd Hill, it’s a great place for a peaceful picnic, while also gazing at some of Canada’s finest historic military buildings.

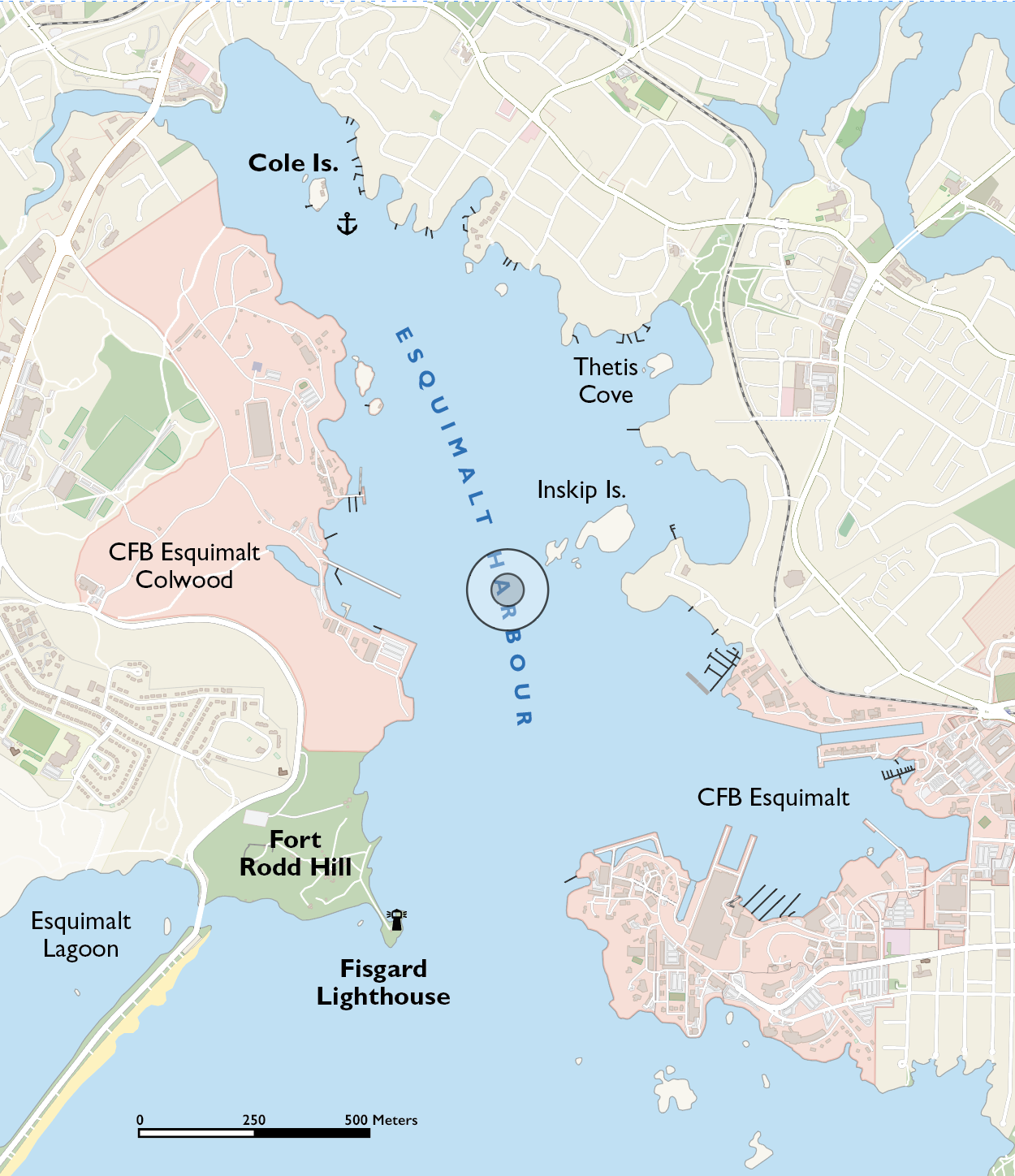

Parts of Esquimalt Harbour are no-anchor zones. The best place for you to drop anchor is south and east of Cole Island (the Island’s west and north side are shallow). Watch the tides. All pleasure craft operators wishing to enter Esquimalt Harbour are asked to report by calling 250-363-2160 or VHF 10. The duty officer will ask for identification of your boat.

Please note civilian vessels must stay out of the 100-metre security zone around all DND ships and facilities.

You can access the beach by Fisgard Lighthouse and Fort Rodd Hill by dinghy, but you must pay your entry fee after walking the causeway to the Fort Rodd Hill Welcome Centre. Fees are waived for youths up to and including age 17.

Some things to keep in mind when visiting the Lighthouse and Fort Rodd: No pets (except registered service animals); no smoking of any kind; no drones without Parks Canada permission. Camping and campfires are prohibited on Cole Island.

If you go

The detailed chart for Esquimalt Harbour is CHS 3419.