Start of a Mystery

This story began a very long time ago. Just how long ago, we are still unsure, but certainly 1,000 years, possibly a great deal more. Yet there is a paradox to understanding this story, and it began in 1995, when a geologist named John Harper was mapping coastal habitat for B.C.’s Ministry of Sustainable Development. Dr Harper was CEO of a small Vancouver Island company called Coast & Ocean Research Inc. (CORI) that had developed techniques to record and interpret shorelines.

Documenting the coast in detail is important for many reasons—oil spill response, urban encroachment, habitat changes, erosion and accretion, to name just a few. John’s group flew aerial surveys in helicopters, charting sections of the B.C. coast and its many offshore islands. As an earth scientist, he analyzed the geology and geomorphology of what he saw. His wife Mary Morris was a prominent marine biologist at Archipelago Marine Research, who identified and quantified the marine life that grew both onshore and off.

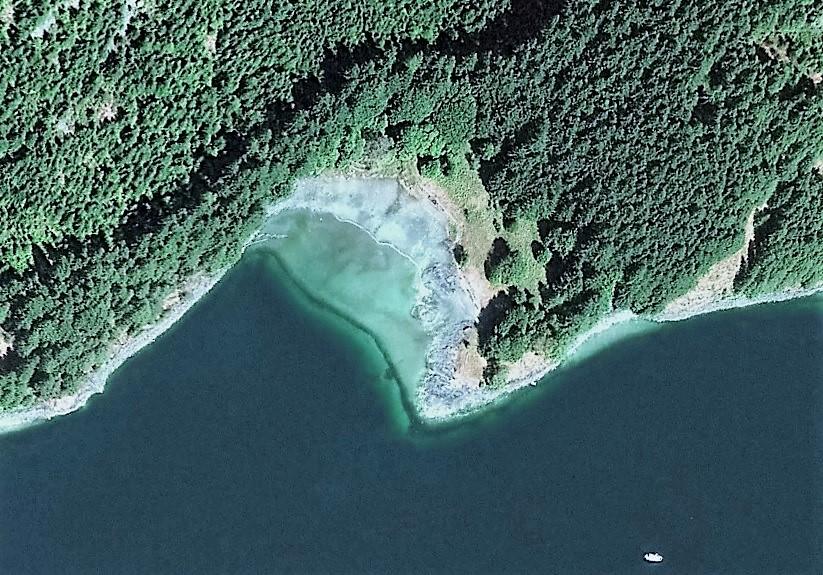

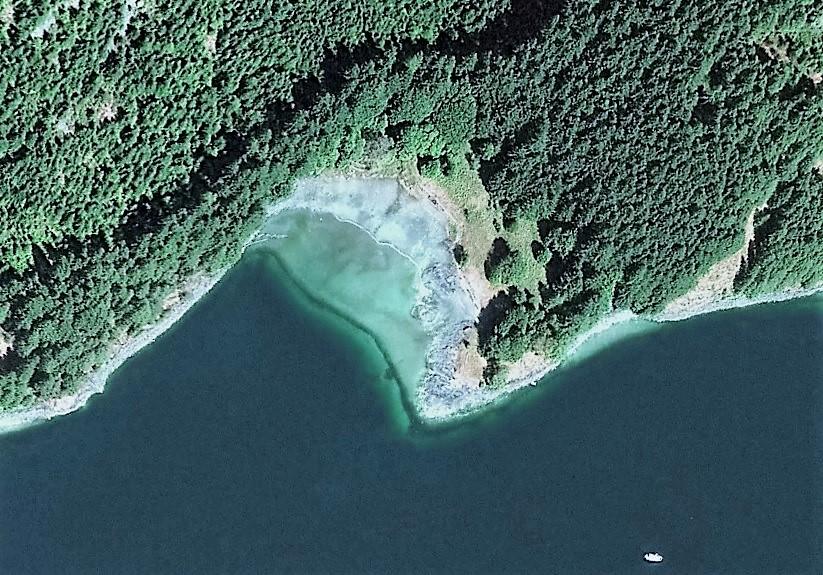

If you’re going to study shorelines, it makes sense to document them when they’re the most visible. That means at spring low tides when maximum beach is exposed. And this is where our story starts, because it was on one of those flights on a June morning in 1995 that Harper saw something that he didn’t recognize. Exposed by a very low tide was a line of stones running across the mouth of a small bay. John wondered what had caused it.

Talking to oceanographers later, they suggested wave action. By this time, John had found over 350 in the Broughton Archipelago. The oceanographers’ explanations didn’t really jibe. While it was true that some of the low tide walls (they looked like walls) faced open reaches where sufficient fetch existed to push up a line of rocks, others, like the first one he’d identified at Tracey Island, faced away from any wave action. No, it couldn’t be wave energy building them. Besides, except at low, low water, they would be covered, and therefore little affected by wave action.

Checking on the Ground

When John and Mary took their 32-foot trawler to the Broughton Archipelago that summer to make a ground inspection, they discovered the walls were made up of angular rocks, which further contradicted the wave action theory. You can’t roll cobbles up and down a beach to form a line, without making them round. Yet those walls were comprised of randomly shaped rocks. They hadn’t been rolled. Most looked like they’d been dropped. And most were basketball size or smaller.

An alternative explanation, that the wall had been formed by recent (Holocene) ice push, didn’t ring true for similar reasons. Glaciers push in one direction, over large areas. They don’t do back eddies. John wondered if they could be man-made, but when he discussed his findings with archaeologists, they either didn’t recognize the structures, or suggested they were ancient fish traps. John had numerous aerial photos of fish traps, and these were definitely not traps—wrong elevation, wrong structure.

Nearly a decade passed. The puzzle about what the walls were ebbed and flowed as other projects came into focus. But CORI continued to fly over more coastline—from Puget Sound in the south to the Aleutian Islands in Alaska—and the problem wouldn’t go away. Every now and then the team came across another batch of walled bays, always at the same tide datum. Ground inspections showed that the areas behind the walls tended to be more level than natural beach slopes and the concentration of shellfish was higher. John Harper dubbed them “clam terraces.”

The scientific literature provided no clue. Dr Don Mitchell, a prominent archeologist who had been active on the West Coast since 1968 was intrigued, but could offer no explanation as to why, if the walls were man-made, they had been constructed at all.

The Mystery Resolves Itself

Finally, in 2002, the puzzle began to unravel. John Harper had just finished reading “Heart of the Raincoast” by well-known marine biologist Alexandra Morton and West Coast icon Billy Proctor (Touchwood Editions, 1998). The book recounted the story of Proctor’s seven decades growing up and living in the Broughton Archipelago. John wrote to Billy, then 68, asking if he knew what the clam terraces were. He included some pictures.

Proctor’s reply surprised John. In his letter Billy wrote: “…to the Natives of this area these are known as clam gardens and were formed over thousands of years.” Then came the clincher. “PS. This is what I was told by the Elders over 50 years ago.”

The following year, John and Mary returned to the Broughtons and met Billy Proctor. They explained that his letter had opened a new area of research, but one thing puzzled them. Why were these clam gardens only found in and around the Broughton Archipelago? Knowledge was widely shared up and down the coast by First Nations. Why would gardens be found only in one specific region?

Again, the answer surprised them. The Broughtons were where some of the densest populations had existed before first contact. In 10,000 years the locals had moved a lot of rocks and built a lot of clam gardens. Billy had himself made one near his home in Echo Bay, to enhance clam yield. Every local island had huge middens, many filled with clams, mussels and barnacles. One had whale bones piled over 40 feet thick.

First Nations Oral Tradition

So they were man-made. But how could the knowledge have been hidden or lost for so long? To understand this, you have to understand the culture of the West Coast First Nations. Knowledge isn’t treated in the same way it is in Western culture. Knowledge may be held by many, but in a culture where there is no writing, it may only be spoken of by a few, and those few may choose not to share it. A famous example of this was the spirit (Kermode) bear on Princess Royal Island. For over a century the bear’s existence was kept hidden from outsiders.

So John turned from established science to traditional ecological knowledge. He met Kim Racalma-Clutsi, VP of the Kwagiulth Museum & Cultural Centre on Quadra Island, Dr Daisy Sewid-Smith, who was the Mamaliliqala Clan linguist and historian, and Chief Adam Dick, who was Kwaxsistalla (Clan Chief and last traditionally trained potlatch speaker of the Kwakwaka’wakw Nation).

Adam Dick had been chosen at the age of four to become a keeper of his peoples’ history. Now in his late 70s, he is the last of his kind. [As an interesting aside, when Margaret Craven wrote her classic I Heard the Owl Call My Name (Clarke Irwin, 1967, which later went on to be #1 on the New York Times bestseller list), she based her character Jim on Adam Dick from Kingcome village.]

It seemed that academe had not been asking the right questions, or had asked the right questions of the wrong people. Now at last the pieces of the puzzle were coming together. Over a long evening in August 2003, Adam Dick and John Harper shared their findings. Chief Dick remembered an old song about the clam gardens. It was a four-verse song, Harper later recalled. Gilford Island songs are all four-verse songs. It was about kids helping their mother, and one of the verses was about going out to help build the clam garden.

The following day they returned to Tracey Island, where it had all begun for John in 1995. There in Monday Anchorage, a shell beach showed evidence of an ancient midden, and across the bay on a small unnamed island, a rock wall revealed itself at low water.

The two of them tramped about as Chief Adam Dick remembered nearly-forgotten stories from his childhood; how when he and his siblings were bored while the adults were digging clams, they were told to carry rocks from the back area to the outer wall. How over centuries the back area had been gradually cleared of rocks, enhancing the clam yield. There were tales of tradition, and ownership, of the handing down of prized gardens through the generations, of their importance in the economy of the West Coast. Adam Dick explained that the gardens needed regular harvesting to be productive. Like land agriculture, clam gardens that were abandoned (as many in the Broughtons were) were nowhere near peak yield.

Sometime in the past, archaeologists documented a sudden change in the diet of the Pacific Northwest First Nations, from surface gathering (mussels, cockles and barnacles) to dug shellfish (butter clams, horse clams, striated cockles, littleneck clams). Was the evolution of the clam garden the cause of this shift in diet, or a result? Certainly, this form of aquaculture was widely embraced by the Kwakwaka’wakw Nation, with over 350 sites identified in the Broughton area alone.

Checking the Written History

Anything this important to the local economy must have had other historical references. John Harper went back to the written record, but this time with a different perspective. Randy Bouchard is an ethnographer who has studied First Nations culture up and down the West Coast since the late 1960s. In an unpublished dictionary he made reference to loqiwey (low-key-way), a word meaning “rolling rocks together.” But the word also meant “low tide mark.” Clearly, the rolling of rocks and the low water line were somehow connected. Then in an ethnographic record by anthropologist Franz Boas from 1906, John found an account of Mink and Wolf where loqiwey was mentioned again. It was important enough to be part of a legend. Then Randy Bouchard dug up a 1934 record, which was likely the first Western written account of clam gardens.

At a place called Klelung, or Orcas Island, there is a clam bed cultivated by its owners. They took the largest rocks that were in the clam bed and moved them out to extreme low water marks, setting them in rows like a fence along the edge of the water. This made clam digging very easy compared to what it had previously been because there are only small pebbles and sand to dig in. It is exceptional to cultivate clam beds in this manner and while other clam beds are used by everyone in the tribe, here only the owners who cultivated the bed gathered.

Bernard Stern, 1934.

Dr Harper published his findings, and the result was almost immediate. Clam gardens started to be found everywhere along the coast from Puget Sound to Alaska, with concentrations in previously heavily occupied areas like the Gulf Islands, around Quadra Island, and in the Broughton Archipelago. Estimates vary as to how many people lived in the Pacific Northwest pre-contact, but the low end is now thought to be 100,000, and possibly several times that number, before smallpox arrived.

The legal ramifications of the clam garden discovery are interesting, as First Nations continue to press their land claims. Until recently, treaty title was only being considered to the High Tide mark. Everything below that was federal and non-negotiable. But under English Common Law, a wall is a powerful demarcation of property, and there is a long established precedent to ownership of land enclosed by a man-made wall. Negotiations continue.

Clam Gardens and You

Once you know what you’re looking for (walls fronting sandy bays at spring low tide), it isn’t necessary to find them from the air. They can be discovered from a headland, even by walking along the shore. The top of the wall is nearly always about 1 meter (3 feet) above low low water datum. An interesting refinement has also been noted. Many gardens have a three to five-metre wide gap in the wall somewhere, to allow a canoe to be pulled up at low tide.

Researchers at Simon Fraser University have dated the walls and found them to be more than 1,000 years old. They also discovered walls that had been built on bedrock. In other words, those structures weren’t used just to enhance aquaculture; they had been constructed to start it in new areas. By 2010 marine ecologists and archaeologists (notably at Simon Fraser University, University of Victoria, Northwest Indian College, and University of Washington) were studying clam gardens from various aspects. Research showed that the addition of a wall increased clam habitat and pushed the yield of butter clams up by four times and littleneck clams by two times.

Modern Clam Harvesting

Captured Vs Cultured

Cultured clam harvests in B.C. are more than double the province’s wild clam harvests. In 2010, of the 2,200 tons of clams commercially harvested, 1,500 tons were harvested from aquaculture operations as opposed to 700 tons from wild capture. In fact, cultured clam harvests are growing at about 15 percent per year, while wild clam harvests have decreased by about 12 percent. Additionally, the total wholesale value of cultured clams was approximately four times greater than commercially captured wild clams in 2010. This is due to the fact that cultured clams are high value, non-native Manila clams while wild native clams have much less value in the market.

Customers

Almost all of the shellfish produced in B.C. is exported, with the U.S. being the number one market. Pentlatch Seafoods in Courtney, for example, exports 95 percent of its clams to the East Coast of the United States and California. After the U.S., Asia is the largest importer of B.C. seafood, with Japan, China, and Hong Kong leading the Asian continent. Consumers prefer to purchase clams live or frozen in the shell.

Competition

The intertidal shellfish industry is highly fragmented with many individual growers. In B.C., there are currently 40 commercial intertidal clam growers registered with the B.C. Shellfish Growers Association (BCSGA). Much of the production takes place in Baynes Sound, with processing undertaken by five companies on Vancouver Island and two in the Vancouver area. According to the BCSGA, the majority of clam seed is imported from Hawaii and Washington State.

Species Selection

The British Columbia coast is home to a number of native clam species. These include littleneck clams (Protothaca staminea), butter clams (Saxidomus gigantean), razor clams (Siliqua patula), sand clams (Macoma secta), soft-shell clams (Mya arenaria), and nuttall cockles (Clinocardium nuttallii).

In addition to native species, there are two common invasive species. The Manila clam (Venerupis hilippinarum) was brought over from Asia in the 1930s, and the varnish clam (Nuttallia obscurata) was introduced to British Columbia in the 1980s. Native species are found in both the northern and southern waters of B.C.’s coast. However, Manila clams are generally not found north of Campbell River, which is likely due to the colder water temperatures of central and northern B.C.