With over 11,000 miles of mainland and island coastline there is much to explore in the diverse southeastern Alaskan panhandle. The snow-packed peaks soar with spectacular grace along the mainland shore, their gleaming granite faces plunging steeply into the ocean. The glistening tidewater glaciers in their inlets are a particular lure for cruisers coming this far north. In contrast, the rainforests and offshore islands are densely green, with trees becoming stunted farther north and severely sculptured by the winter winds on the rocky west coast.

The innumerable channels and tranquil anchorages are not only stunning but also teeming with birds, whales, dolphins and fish, with bears a common sight ashore. The region has a rich native presence and a well-documented and intriguing history. Seventy-five percent of this region’s population lives in just five towns, and they all have unique personalities. As do the smaller, off-the-beaten-path communities.

Planning a Trip As the Alaskan panhandle lies in a migratory low-pressure system, the whole region lacks a settled sunny summer season and has an annual rainfall of 160 inches. The average June-August highs run from 15 to 20°C. With the usual onset of fog during July, most cruisers plan to enter Alaskan waters by early June and generally leave during August to achieve good-weather passages north and south.

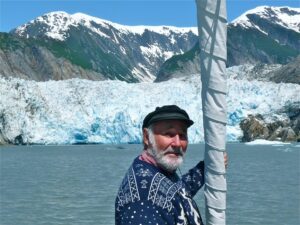

On our recent trip my husband, Andy, and I left Vancouver in our 40-foot Beneteau, Bagheera, on May 15 and returned August 15, covering 3,000 miles. We motored and motor-sailed much of the time but had some good sailing too, although never for an entire leg. Fortunately, the long summer daylight hours and typically calm seas allow many miles a day, and the contrasting scenery and abundant wildlife assure they fly by fast.

Wherever you go in the Alaskan panhandle, your time frame and the large mileages involved, the unsettled weather, the speed of your boat, your Glacier Bay permit and the hours your crew is willing to spend underway will all influence the extent of your visit.

Many cruisers will get only as far as Juneau, with Tracey Arm as their tidewater glacier experience. Others have Glacier Bay in their sights and aim to deadhead there in hopes of a free slot if they haven’t been able to obtain a permit in advance. In our opinion, Sitka is a jewel that should not be missed but it hugely increases your mileage. Mileage too is deceptive. Although it is 750 miles as the crow flies from Vancouver to Skagway we logged four times distance that only going as far north as Juneau but including Sitka and the west coast, as we had been to Skagway and Glacier Bay before.

Entering Alaska Exposed to the Pacific Ocean and frequented by fronts, the 20 miles of unprotected water at Dixon Entrance north of Dundas Island, that divides Canada and the U.S., can be a turbulent body of water, particularly when the swift outflowing currents from Portland and adjacent inlets conflict with an opposing wind.

Friendly Cow Bay in Prince Rupert is a comfortable, convenient place both to provision (for goods allowed into the U.S.) and to watch the weather. Environment Canada and NOAA give frequent forecasts and actuals from reporting stations such as the significant Central Dixon Entrance Buoy.

The distance from Prince Rupert to Ketchikan, for U.S clearance, is about 80 miles when taking the shallow, winding Venn Passage. U.S. Customs understand a stop en route may be required but request a phone call (907 225-2254) ahead of time. Foggy Bay, Alaska, 50-miles north of Prince Rupert is a popular overnight stop but there are many anchorages to chose from, including waiting at Dundas Island before arriving in Ketchikan. We anchored between Ham and Annette Islands in peaceful bliss until a parade of cruise ships passed in Revillagigedo Channel outside, bringing us back to reality.

Next morning we set the clocks back an hour to Alaska Daylight Time, ADT (all of Alaska except the nearby community of Metlakatla are in this time zone), realizing that we had come nine degrees west in longitude and six degrees north in latitude since leaving Vancouver. We had chosen to dock in Thomas Basin, the old fishing port by the cruise ship dock in Ketchikan and one of five public boat harbours on the east bank of the Tongass Narrows.

Although convenient for Customs and sightseeing we later found it had no shower or internet. We contacted Customs on Channel 16 and were courteously cleared without having to leave the boat and with the usual $19 for a U.S. Customs Border Protection user fee. We were also reminded we needed a license for fishing, clamming and prawning. When walking to the convenient public bus for the harbourmaster’s office at the Bar Harbor Marina to pay our moorage fee we were deluged by rain. It lasted two days and we were happy to spend the two nights at the dock plugged into shore-power and we bought an extra heater to dry out and warm up onboard.

“Rain is quite usual here, as we are in the heart of the 17 million acre Tongass National rainforest that covers most of the region,” we were told in the local coffee shop. “I am a true Alaskan,” she added proudly, informing us that the town’s population of 8,000 swelled in summer with transients to work the souvenir shops and run the water and inland tours. It is the same at all the cruise ship ports on the tourist trail and one of pleasures of cruising to these remote regions is meeting the true locals.

Ketchikan Named “Alaska’s first City,” as it was the first stop for mail, Ketchikan has a colourful history. Originally the site of a Tlingit fishing camp, it was visited by George Vancouver in 1793 and became rich during the 1880s as a fishing and logging centre.

The nearby Tongass Historical Museum has excellent visual and written displays about the region’s development as well as rich Tlingit artifacts. The photos of fishermen hauling in nets bulging with fish (1936 was the Alaskan record catch off 126.4 million fish) are particularly thought provoking in view of the current stocks.

Touring the various parks that house the world’s largest collection of totem poles is also impressive, along the Totem Heritage Center that preserves and promotes the traditional arts and crafts of the Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian through classes that teach carving, tool making and basketry. The attractive old houses on historic Creek Street, formerly the red light district, are built on piles and connected by boardwalks, and now have shops selling local arts and crafts. Some claim to still have their original furnishings.

Sadly we had to give the spectacular Misty Fjords Monument region to the east of Ketchikan a miss but with a brilliant rainbow overhead and the black clouds lifting we sailed north in Clarence Strait averaging seven knots, boosted by the wind and current—and a little motoring. We stopped en route to watch a black bear fishing along the beach and visually followed a few hump-backed whales along the 60-mile route to Frosty Bay on Cliveland Peninsula in Ernest Sound. A scarlet sunset was a perfect sundowner. The next morning the bands of fog cleared early, and the sun came out for a no-jacket day as we weaved through the well-marked channel in beautiful Zimovia Strait.

Wrangell We arrived at Reliance Float in Wrangell and instantly bonded with this happy town. The nearby officials were informal, and our new dockmates greeted us warmly as they stocked their boats for the upcoming fishing season, recounting stories of previous salmon successes. One neighbour came for a drink bearing a pail full of prawns, and with his tales of living in Ketchikan as a cruise ship lawyer we began to feel we were truly cruising Alaska.

Although Wrangell is visited by a few cruise ships, it is a working town and has one of the best climates of the region. It has a diverse international background, as well. For centuries it was an important trading post for the Tlingit Indians, its impressive petroglyphs are estimated to date back 8,000 years. The Russians built a fort here in 1834 to guard against the Hudson Bay trappers, later the British leased the area and it even had a mini gold rush during the late 1800s.

This well-stocked town is full of character with murals along the main street together with carvings, some even on the roofs. Accessed by a short walkway, Shakes Island makes an interesting visit. Chief Shakes Tribal house stands in the middle, unfortunately closed on our visit, but the huge large totem poles are treasures.

It is also good for bird watching with eagles, murres, murrelets and herons in particular abundance. Offering many hiking trails, the Anan Bear and Wildlife Observatory (best in July and August when the salmon are running) and delightful nearby anchorages, this is definitely an area one could linger in for a while.

Continuing Northward The clarity of the snowy mainland mountains was surreal as we left for Petersburg in a tranquil calm and made our way to the southern entrance of the winding Wrangell Channel, timing our arrival with the favoured flood tide and aiming to arrive at Green Point at high tide to then benefit from the northerly ebb.

Twenty miles long with 63 navigational aids, the channel needs some concentration. We were passed by an Alaskan Ferry, whose crew courteously radioed ahead and suggested we pull to the side while they pass. The ferry carries cargo and passengers to numerous communities in Alaska and is apparently a great way to travel with its hop-on /hop-off policy.

The backcloth of mountains, particularly the renowned Devil’s Thumb, make an arrival at the busy fishing town of Petersburg memorable. The harbourmaster assigned us a berth when we called ahead on VHF Channel 16. We were close to town, but unfortunately it was hard to get around due to extensive road works. The tourist office is very informative and friendly and we learned that Petersburg—population 3,000—was founded by Norwegians in 1897.

Ice in Tracy Arm The first icebergs appeared north of Petersburg in Stephens Passage, and this was the start of an exciting time. Passing some enticing anchorages en-route, we completed a 12-hour, 74-mile passage to the entrance of Tracey and Endicott arms. Off Endicott Arm is Ford’s Terror, a dramatic narrow channel that offers a thrill for adventurous boaters with its eight-knot current and packed ice. We had been informed it was currently completely blocked with ice. Instead we followed the lead markers into Holkham Bay with a three-knot current against us, then anchored in a small unmarked bay two miles north on the west side.

That evening we enjoyed watching the Arctic terns, eagles, kittiwakes and pigeon guillemots, and reading about the Red Tree Coral, a gorgonian sea fan that grows to eight feet tall and is found in the dark, glacial waters.

The mile-wide fjord of Tracy Arm is a spectacular stop, certainly rivalling the much larger Glacier Bay. Winding 25 miles inland, generally little more than half a mile wide with mountains towering to 4,000 feet on either side, its vertical cliffs, forests, teeming waterfalls and tidewater glaciers make for wondrous sight-seeing, especially with a cloudless blue sky that was our luck.

We timed our arrival for the late morning hoping to avoid the cruise ships and local tourist boats and have the North Sawyer Glacier to ourselves. Every bend offered another stunning sight until we reached the confluence of North and South Sawyer Glaciers’ outflows solid with ice. Knowing that up to 90 percent of an iceberg lies underwater made for some uneasy navigation. I searched for a passage, knowing Andy would want to turn back, and finally found one by the south side of the channel. With Andy at the helm I directed from the bow and gradually we weaved our way through icebergs of amazing shapes and sizes, relieved to find that a break from the ice within a mile of the North Sawyer tidewater glacier.

To have our boat so close to the glistening cracking turquoise ice was surreal. We were all alone, it was so silent, until, with an echoing roar, a huge chunk of ice calved free and entered the aqua ocean with a resounding splash. Silence again, then a birdcall, and then an eerie echoing around the bay. Then silence. It was magic and we had it all to ourselves for 25 minutes.

Juneau Rather than returning by the same route many cruisers continue 45 miles north to Juneau. Originally a gold-mining town, the busy tourist-oriented Alaskan capital can only be reached by boat and plane.

Nestled between Mount Juneau and Mount Roberts, with the memorable ‘walk-in’ Mendenhall Glacier above, its 33,000 people make it the largest city in southeastern Alaska. There is a scenic approach along the eight-mile Gastineau Channel, but because of the 60-foot bridge and shallow channel north of Juneau that dries at 10 feet, many cruisers prefer not to backtrack and go straight to the northerly Auke Bay. Whether continuing to Skagway, Glacier Bay or heading south, Juneau has excellent facilities to stock up for the rest of the Alaskan marvels that are yet to come.

[SIDEBAR] If You Go

Weather forecasting on VHF radio is reasonable although reception may not available in remote regions and in steep-sided fjords. Those with an SSB radio can listen to the Great Northern Boaters’ Ham radio net. (3870 KHz commences April 15 at 06:30 Alaska time (07:30 PDT) with a roll call at 07:00 Alaska time (08:00 PDT). Cell phone coverage and internet are available only in the centres. This region is not only vast but can be extremely remote, with few communities or boat traffic, which, along with the weather and current considerations, make a well-maintained boat, reliable engine, radar, enclosed cockpit, good heating, warm, waterproof clothing and self-sufficiency, essentials to comfortable cruising. Up-to-date cruising guides include the Waggoner to Ketchikan 2014, Northwest Boat Travel 2014.