“From the frying pan to the fire, they say. From gales to calms. As wonderful as it is, as welcome as it is, we cannot linger. It is a trap and if caught napping and [staying] below the ridge building over the next few days, we may yet be barred from the refuge of the Southeast trades.”

Thus writes Bert terHart in his blog on May 25, 2020, seven months into his circumnavigation. In this blog, with daily entries and a photo, readers around the world followed his lonely journey, learning about his constant weather vigilance, doldrums, contrary winds pushing his sailboat off course, endless gales, taking sights with his sextant, setting and lowering sails, navigating, sunrises, sunsets, intermittent sleep—the daily events aboard a small sailboat controlled by a single person.

We learn about the inevitable breakdowns—when, for example, off the coast of Oregon, Bert believed his fuel tank’s loud banging indicated it was breaking loose. “The noise was unreal,” he told me. “A sledgehammer effect. I could feel the cabin sole coming up.”

Knowing he could never cross the Pacific and Southern oceans with an unchained tank, he diverted into San Francisco, and learned the tank only suffered from being overfilled with diesel (for charging batteries). Or when a sudden lurch resulted from the Monitor windvane’s control lines having chafed through. Or when a few of the mainsail’s plastic sliders came apart in the Southern Ocean. (With his usual ingenuity, Bert repaired them by drilling holes in the plastic bits and tying in Spectra line secured by Super Glue.)

He sums up the difficulties of anticipating equipment failures on May 9, 2020, “Given the complexity of the boat, the extreme environment, and the duration of the voyage, the list of things that could go wrong is daunting… It is impossible to carry enough bits and pieces to cover all eventualities so you must decide what’s ‘mission critical’ and what is not… My biggest fear was that some $2 piece of plastic would sink the whole caper.”

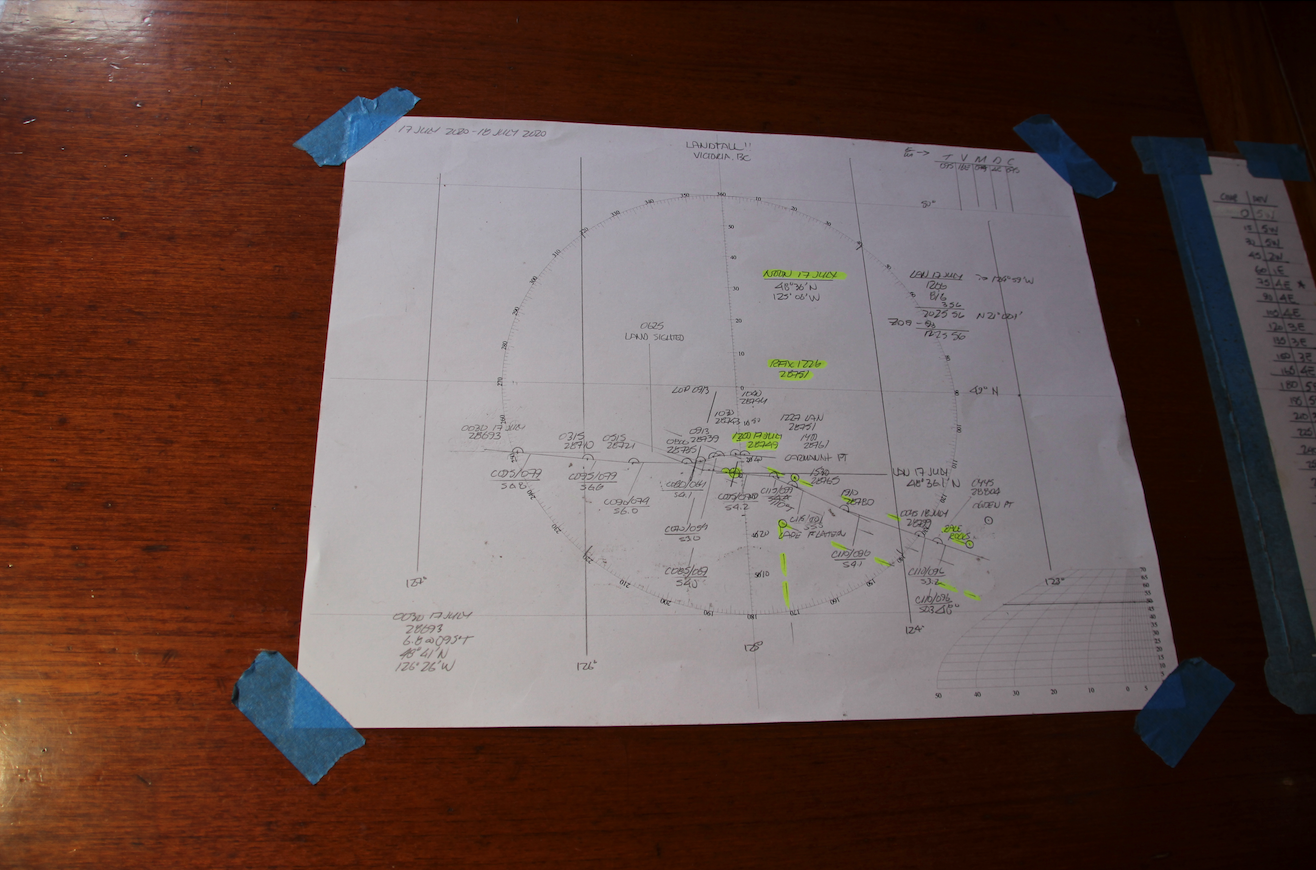

Bert terHart left Victoria, BC, on October 27, 2019, with the goal of emulating solo navigators who travelled half a century or more ago—without electronic charts, or GPS. Thus, he passed the five great southern capes going east using only a sextant, paper charts, pencil and log tables—a feat previously accomplished by eight single-handing sailors in the past, but none of them starting from North America.

Following in the tracks of such solo voyagers as Sir Robin Knox Johnston (1968–69), Chay Blyth (1971) and Bernard Moitessier (1960s) who circumnavigated before the widespread use of electronic navigation equipment, Bert has joined several other circumnavigators with a special place in the record books—Laura Dekker, the youngest ever circumnavigator; Victoria-based Tony Gooch, the first solo non-stop sailor starting from the North American West Coast; and British-born Jeanne Socrates, both the oldest woman and then the oldest person to have completed a solo circumnavigation.

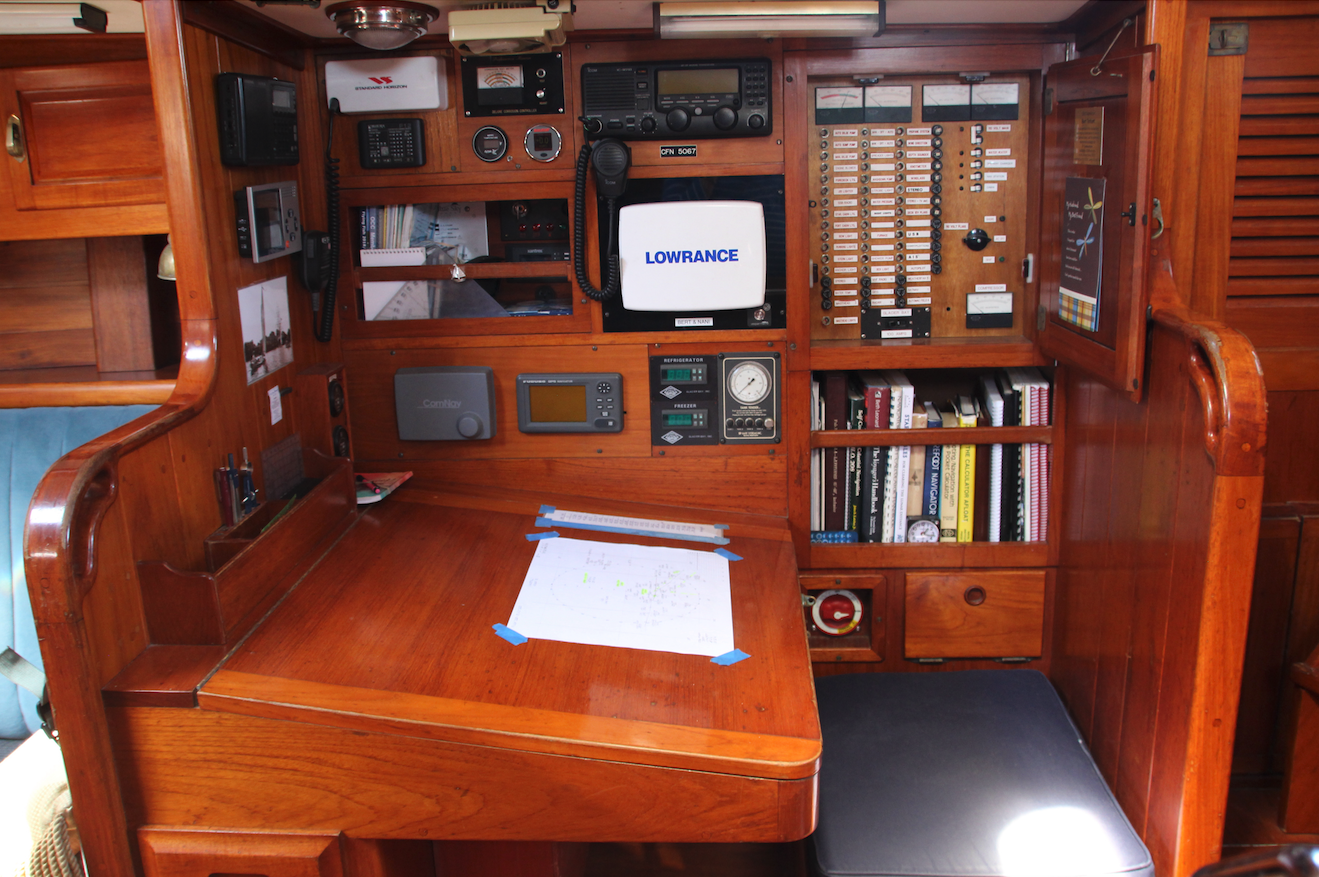

Bert returned to Victoria on July 18, 2020—265 days after departing—having sailed 28,820 miles. I met Bert a few days after his return to Victoria and visited his 45-foot Seaburban, an OCY sloop built in 1987 in Hamilton by Hank Hinkley and a Canadian partner, a sturdy vessel designed by Montreal-based Pierre Meunier. The nearly nine months in salt water, sun and storms had removed some varnish from the brightwork, but other than that the yacht was spic and span. When I went below, I was struck at its extreme orderliness—everything was tidy, in its place, clean and shiny.

Bert himself follows this pattern. He’s 61, lean and fit. “I started running out of food toward the end,” he said. “When weather delayed me, I was down to 800 calories a day and lost 20 pounds.” Clean shaven, he, like many of his Dutch heritage, is tall, blue eyed and sports a greying brush cut. The only physical damage from his lonely voyage is a swollen knee, due to an earlier rugby injury and now inflamed by the endless kneeling when adjusting sails and knocking into things balancing on a continuously moving boat. When I ask him about it, he dismisses the damage as minor and temporary.

Although not born anywhere near an ocean, Bert started sailing small boats on Carlyle Lake, near Estevan, Saskatchewan. “My dad, Jan terHart, took me sailing on what was really a reservoir that provided cooling water for a nearby power plant,” Bert says. “We had a cabin there and we put sails on everything that floated: canoes, even tractor tubes.” After high school, Bert enrolled at Royal Roads in Victoria, studying physical oceanography and wanting “desperately” to enter the Royal Canadian Navy as a maritime engineer. Alas, his colour blindness prevented him from reaching that goal. “I had a choice,” he says. “Quit or go into the army.”

He chose the army and served the required four years. “I was first stationed in Victoria with the Princess Patricia Canadian Light Infantry,” he explains. “Part of my job was to ensure that everything worked—from typewriters to tanks. It helped later while circling the globe.” He lived aboard a ferro-cement boat while stationed on the Island. “The boat had offshore experience,” he recalls. “I’ve always wanted to go to sea.”

He also qualified in parachute jumping and in 1983, joined the Canadian Special Operations Forces Command. “It’s an elite service,” Bert explains. “Somewhat like the Green Berets or the Navy Seals. Again, my job was to keep everything operational.”

After his military service, he enrolled at UBC’s doctoral physical oceanography program, studying the return migration of sockeye salmon, a huge multidisciplinary project. Along the way, he realized that these studies would likely lead to an academic career, one he knew wouldn’t suit him. He finished a master’s degree instead, and with a former Royal Roads professor worked on programming 3D analyses of vertical and horizontal water columns—a turbulent math problem. He took to the task enthusiastically. “We’d jump into a boat and take measurements at sea,” he says.

That programming led to the next step: working with a friend in Los Angeles to develop software for cardiologists designed to streamline patient data and make it more comprehensive. “I wanted to make a contribution, both in salmon tracking and clinic management that puts patients on the road to wellness,” he says.

Eventually, he returned to Canada, settled in Abbotsford, then, in 2007, moved to Gabriola Island, building his software company while working remotely well before the pandemic. He continued to refine the modal system software for health care professionals, with the goal of delivering more treatment options for physicians. To write code, he contracted with programmers in eastern Europe and Asia. That same year, he found the right boat, naming her Seaburban. “I always bought used, sometimes beat-up Suburbans over the years, so when I found the OYC, a double-headed foresail sloop, my daughter Kathryn told me to adapt the truck’s name,” he smiles.

Seaburban, with its Beta 43, four-cycle Kubota-block tractor engine, got a good workout over the years. “We sailed as far as the Aleutians and the Bering Sea, a tough voyage,” Bert says. “We also circumnavigated Vancouver Island five times, explored Haida Gwaii, and had a shakedown cruise to Alaska—all of which gave me experience for the circumnavigation—the voyage I’d long aspired to.”

Preparation began in earnest about a year before departure. “I’d anticipated the journey to take about seven months or about 210 days, slower than Tony Gooch’s 2002-2003 solo circumnavigation [177 days] and not venturing as far south,” Bert says. “Tony sailed at 47 degrees south, while I stayed at about 42 to 43 degrees.”

Several events slowed his progress, including 55 days of being becalmed. In addition, when nearing the Falkland Islands, Bert decided to wait out a forecasted hurricane at anchor in the Falklands’ Stanley Harbour—a port of refuge. “I lost a week getting there and an additional 10 days hooked down in winds up to 85 knots,” he recalls. “I never left the boat and took off again after the hurricane.” He was also slowed by being forced to put away his 110 percent jib. “It was just too big in too many circumstances,” he says. Instead he used a 90 percent yankee on a steel halyard until it blew apart and he was left with a 70 percent solent headsail.

To stay safe, Bert equipped Seaburban with radar (which drowned in the Southern Ocean), AIS, VHF, EPIRB, a six-person liferaft, an abandon-ship bag and jacklines. He brought along a GPS and a chart plotter for security but never activated them. “I always wore a short tether on board,” he says. To stay in place while sleeping in the ever-rolling vessel, even with lee cloths, he used belts to tie himself down to the settee. He set an alarm to avoid sleeping for more than two hours. As his water tanks carry 480 litres, he forwent a watermaker. His twin fuel tanks hold 600 litres. The lead-crystal, fast charge, high-tech batteries kept his slow-use electrical needs going. To charge them, he used a 30-year-old tow generator. “I used a 100-foot line with a prop attached,” he says. “It charged the batteries continually, although I didn’t deploy it during storms.”

He brought along 600 feet of warps, a Fiorentino Shark steering drogue that helped keep the boat on track, and a Jordan Series drogue ready to deploy quickly. “To retrieve the Jordan, you have to have very calm weather,” he says. “The winds varied throughout the trip. I experienced gusts of 75 knots, and sometimes sustained blows of 50 knots. But as I received the weather forecasts from Gabriola-based John Bullas, I could avoid some of the big gales.”

That said, he suffered knockdowns in the southern Tasman Sea and the South Pacific. “The mast was under water during the first knockdown,” he says. “I worried about flooding although I’d taken off the dorades. The next time I was standing on the cockpit coaming when a 55-knot gust built waves that flattened the boat,” he says. “The spreaders were in the water. I wasn’t hurt. I was scared but not paralyzed. It’s important to know you can be scared s***less, but not witless.”

How much food should Seaburban carry? This is a huge question for a solo navigator and Bert underestimated the amount. “I figured 2,500 calories a day was enough to keep going,” he says. “But the constant motion and work, plus intermittent sleep demanded more. Fortunately, I’m not a fussy eater.”

Indeed, he is not. His daily rations were mostly repetitive: rice, quinoa, pasta, canned tuna and salmon (he didn’t fish), oats, granola, cans of chili and ravioli, dried fruit and nuts. In the beginning, he had some potatoes and onions. He also consumed vitamin C pills and magnesium and selenium supplements, while minimizing his salt intake. He’d decommissioned the fridge, so couldn’t draw on frozen fare, but saved amps. With the delays and his stores running seriously low, he’d rationed himself to 800 calories a day—a starvation menu. Despite his protestations, his sister, Leah terHart, arranged with Rarotonga islanders, Kyle and Bob Matheson, for food and diesel to be delivered to Bert’s boat when he passed by the island on May 26, 2020. They did this on short notice and despite COVID-19 restrictions. Bert will be eternally grateful.

Bert communicated by Iridium email and text. “My single-sideband radio died off Baja,” he says. “It was a big loss.” Nevertheless, he kept in touch with family and friends by emailing Leah who then posted on Facebook and the blog. He answered questions from school kids in various countries around the world. He was alone, he says, but never lonely, except that he found it tough having no one to share meals with.

“What does it take to accomplish a solo circumnavigation?” I asked. “The major characteristic,” he responded, “is persistence. Planning, preparation, prudence, yes, but in the end, persistence. I set out to do something, I was persistent, and I finished what I started.”

Although one might think this stick-to-it guy, capable and practical, always busy doing something during his near-nine months solo survival at sea, might have had little time for reflection. But he often blogged about the majesty of the sea, the sunsets, the power of wind and waves. During one poetic stretch, he blogged:

Alone and quiet, bathed in splendour, you can almost feel the pulse of the world. There is not much between you and the heartbeat of the universe. Between you and creation. It is truly a Thin Place.

Bert terHart’s blog can be found online at the5capes.com.