The last time I was in Heiltsuk territory visiting Bella Bella I encountered two coastal Guardian Watchmen. From them I learned a little about the country-wide program, which includes environmental monitoring and cultural interpretation and I made a plan to go back this summer and discover more.

My idea was to spend some time with the Guardian Watchmen—learning about what they are doing and what their goals are, and then share that story with Pacific Yachting readers. Instead, Covid-19 happened. Since then a unique coalition of Central and North Coast First Nations including the Haida, Heiltsuk, Metlakatla, Gitxaala, Gitga’at, Nuxalk, Wuikinuxv, Lax Kw’alaams and Kitasoo / Xai’xais Nations have implemented restrictions against non-essential travel to their regions.

This meant the Guardian Watchmen story I envisioned would have to wait.

For many of us, being asked to stick close to our own home waters and keep away from Indigenous communities and territories is a straightforward request. While it’s disappointing not to be out exploring the gorgeous coastal regions this year, the idea of Covid-19 entering any of the remote First Nation’s populations is too horrific to risk. For others, the request to stay away might seem extreme, especially as the province itself is opening back up and marinas and marine parks are welcoming boaters.

So rather than completely abandoning the story I planned to write about Guardian Watchmen—I decided to take it in a different direction. Using my fledgling coastal contacts, I phoned leaders in Bella Bella and Klemtu and asked Chief councilors Marilyn Slett and Roxanne Robinson to tell Pacific Yachting how their communities came to the decision to restrict visitors. Despite being busy, both women generously offered context around why they are asking for our support and respect.

The simple explanation is that Indigenous communities have limited health care facilities and the population has experienced high levels of trauma, poverty, household crowding, and illness, which make the people especially vulnerable to Covid-19. As we talked though, I learned there are deeper cultural reasons.

“Our laws and traditions are oral,” Marilyn Slett told me. “They’re passed down by our Knowledge Keepers,” a group of Elders who have learned the Nation’s customs, traditions and protocols. And protecting these Elders is essential.

During my visit to Bella Bella I was fortunate enough to spend time with some of the community’s Knowledge Keepers. Over a meal of herring row on kelp, salmon, eulachon grease and specially made (for me) gluten free bannock, we were taken back through a history that many Canadians are just beginning to contend with.

For 14,000 years the Heiltsuk have lived in balance within a territory that spans about 15,540 km2 and extends through The Great Bear Rainforest. Heiltsuk historians estimate that at their cultural peak as many as 20,000 people lived in 50 summer and winter villages set in ancient forests of huge Sitka spruce, red cedar, western hemlock and Douglas fir.

European contact, dating from the 1780s, brought intentional devastation: small pox, measles, and government policies like the residential schools, which were intent on extinguishing the language and culture. The onslaught took its toll. In the 1880s, the last remnants of the severely depleted Heiltsuk communities gathered into one village near Bella Bella: the Heiltsuk population had been diminished to around 200 people. Many cultural practices were illegal. Those practices that were maintained, were often done so in secret.

This quiet resistance is what sustained the community through years of poverty and systemic racism. Slowly the community has been able revitalize their culture (a process that reached a milestone with the November 2019 opening of the community’s first Big House to be built in 200 years). Their work isn’t done though, and with only 30 fluent Hailhzaqvla (the language of the Heiltsuk) speaking Elders left—the community decided to take control of their own destiny.

So the Heiltsuk Nation, like many Indigenous communities in coastal BC, and around the world enacted a strict lockdown; opting to go well beyond provincial guidelines by banning all non-essential travel into or out of their territory.

Located 55km north of Bella Bella, the Kitasoo / Xai’xais village of Klemtu is also on lockdown. Chief Councillor Roxanne Robinson says the decision to close the community to outsiders was an obvious one, “protecting the health and safety of people is the work of a leader.”

The rugged landscape and wildlife, which includes whales, coastal wolves, black bears, grizzly bears and the spirit bear, attracts visitors and boaters from all over the world. And tourism makes up a vital part of the local economy. Robinson says it was a difficult decision to close their community. But when reports from Bella Bella started coming in about yachts making their way north, and Guardian Watchmen were doing their best to turn them back, they acted quickly.

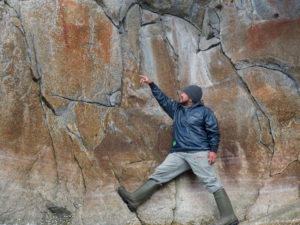

I encountered these same Guardian Watchmen during my visit months before. I was on a half-day cultural boat tour, and while I’ve spent lots of time boating in the area, this was the first time I’d seen it through the eyes of its Heiltsuk custodians. As we were taken to see pictographs (which some researchers think provided information about territorial boundaries and food sources), ancient fish traps and a sacred village, the Guardian Watchmen checked in.

In normal times the Guardians act as friendly ambassadors and cultural interpreters, ensuring people knew to stay away from sacred sites and to follow wildlife regulations. They’re also there to exert rights over their territories. “They are an extension of nationhood,” says Claire Hutton, the Indigenous Stewardship Director at Nature United.

Modern Guardian Watchmen programs came into being in the 1980s with programs in Haida Gwaii and in the Innu territories in Labrador. Today over 50 different programs across Canada fulfill a wide variety of different roles—depending on what a community may need.

Hutton, who coordinates a team that provides technical support to Indigenous Guardians across Canada, says the programs are as distinct as the Nation’s themselves; but there are common themes and issues. Many are focused on stewardship and ensuring the protection of traditional food sources and other important values. Some have a strong science focus and Indigenous Guardians are critical for data collection and monitoring biodiversity, important wildlife or species at risk. Some are focused on tourism and the Guardians act as interpreters.

Right now Guardians are finding themselves manning checkpoints and patrolling their waters. Logging the details of every boat that enters their waters and passing along the information to neighbouring Nations. This new responsibility has brought up an unexpected set of needs. “Offering conflict training and Tactical Communications webinars is new,” Hutton says.

As the Guardian Watchmen have moved to the frontlines and communities have closed down, they’ve encountered pushback from boaters and travelers who question their authority. While British Columbia’s Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation agree that First Nations do have the authority to restrict travel into their communities, at the same time the province, like many places, has begun reopening, forcing Indigenous communities to protect themselves.

So Slett and Robinson explain that this is where Pacific Yachting readers come in. They want tourists; they want visitors, but later. When things are different— boaters are encouraged to visit the communities, learn about the culture, see the magnificent big houses and maybe even take a cultural tour.

But for now Slett says they need to get everyone through the pandemic safely and to do this they as we stay away, “one of our staff members posted this on Facebook: “We are self-isolating at this time so that when we gather again, nobody is left behind.””

Click here stay current on travel restrictions in the coastal communities.