25 years ago, Winston Bushnell (skipper), George Hone (first mate) and I (artist/writer) sailed the Northwest Passage aboard Dove III. Winston was a well-seasoned mariner, having sailed around the world during the ‘70s with his family aboard the small sailboat, Dove, which was rolled over off South Africa by a 60-foot wave. George was an experienced sailor. Although I was living on a 42-foot ketch Dreamer II, I was still a novice. Winston built Dove III (Brent Swain design) specifically for sailing the Northwest Passage. Only 27 feet long, she was made of steel and had a shallow draft, which would enable her to battle the remorseless ice while tightly hugging the shore.

Winston’s first plan to sail the Northwest Passage was to take only one crewmember. I’m not sure why he decided to take on more crew, especially someone like me, but maybe it’s like he said, “At least you won’t mutiny.” I think that sums it up best.

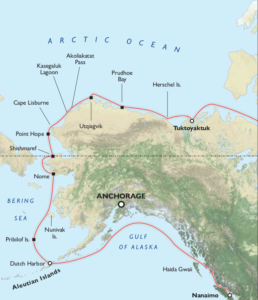

On May 8, 1995, Dove III left Nanaimo, BC in her wake. I remember wondering if we would ever return. As we sailed up the inside passage to Prince Rupert, except for an occasional squall, the going was very pleasant and relaxing.

After leaving Prince Rupert, we were soon sailing past Tow Hill on Haida Gwaii, which brought back fond memories of camping at its base. Once land had completely disappeared and only sea and sky remained, the wind reached gale force velocity and the ocean went berserk! Although the boat pitched about like a drunken sailor for a few days, she handled the storm well, which gave me added confidence as we headed farther and farther north.

The Aleutian Islands seemed dark and foreboding until we reached the first of several designated destinations, Dutch Harbor. After being at sea for almost three weeks, it felt great to get in touch with our loved ones back home. We stayed longer than we wanted due to a violent gale blowing across the Bering Sea. Anxious to be on our way, we set sail with high hopes that the wind would die down, but it did just the opposite—it blew harder. We were forced to heave-to in two to six-metre seas. The fierceness of the storm blew us off course and we drifted toward the Pribilof Islands. I hadn’t really been worried about our safety until a concerned looking Winston exclaimed before my turn at the wheel, “Keep your eyes peeled Lenny! One of those waves could roll us over!”

A few thoughts crossed my mind: how long would the ferocious weather last, how long before a rogue wave the size of a semi knocked us over and how long would we survive if we lost the boat? Two days later, after the wind and the sea had calmed down considerably, we were back on course and finally dropped the hook in a quiet little bay off Nunivak Island. Now, halfway across the Bering Sea, we were grateful for moments of tranquility after that tremendous storm.

I was really looking forward to our next destination, Nome, Alaska. Entering the little port was a little tricky (only 1.5 metres at the entrance) but Winston, with a little advice from the US Coast Guard vessel, Storis, soon had us safely inside the protected moorage and tied to a small dock.

While waiting for the ice to break, I enjoyed strolling around Nome, photographing and videoing the sights, which looked much like an old “wild-west” town. Nome was established during a gold rush around 1901. After a few days on land, we headed toward the ice pack and two days later, after crossing the Arctic Circle, we were in the thick of it! Cutting our way through the ice was a little unnerving and we were soon forced to retreat to the village of Shishmaref, located on tiny, banana-shaped Sarichef Island.

When we managed to reach Point Hope the next day, the first of many curious Inuit hunters arrived. They told us the sea was free of ice all the way to Cape Lisburne. Upon arrival at the US DEW Line aircraft base, established during the Second World War, we were greeted by the overseer. The overseer treated us, like many of the people we met, to a great meal and much needed showers. Our short stay was a little unsettling because only a tiny stream kept the approaching ice away from the hull. When a sudden squall roared in over the mountains and blew the ice away, we left in a hurry. Hoping to escape its fury, we tucked into the Thetis Creek, which almost ended our voyage. The river was very shallow, and we were almost swept onto a sandbar.

Manoeuvring through tight leads (long narrow gaps in the ice) can be very tricky because they could abruptly end or suddenly snap shut. We took turns up in the ratlines, pointing out the way. And, as luck would have it, we came to a dead end and were forced to tie to a large chunk of ice. When the lead reopened, we almost made it to Kasegaluk Lagoon, before being stopped once again. It seemed like I’d just crawled into my sleeping bag when Winston hollered, “Time to go boys! A little gust of wind just blew the ice out! Let’s try to get into the lagoon before it closes in again!”

It was a good call on Winston’s part because the ice blew in with a vengeance and stacked up on the shore about three to four metres high. If we had stayed, little Dove III, would have been knocked over and possibly crushed—a tragic end to our voyage. Over the next few days, we played cat and mouse with the ice, ducking in and out of Kasegaluk Lagoon.

July 8, two months after leaving Nanaimo, we reached Akoliakatat Pass, another cut leading into the seemingly endless lagoon. Surrounded by swirling ice at the entrance, George at the bow with a pike pole, I yelled down from the ratlines to Winston at the helm, “Give’er!”

Winston opened the throttle as two huge ice floes rapidly closed our narrow gap to safety. We didn’t quite make it! When the bow rose out of the water and the boat heeled over on its side, I wrapped both arms around the mast and held on for dear life! Fortunately, the boat slid across the ice and soon righted itself. Even though we were inside the lagoon, it took some time to escape the ice that was flowing in right behind us.

When we finally bashed through the ice to the bustling town of Barrow (now known as Utqiaġvik), we were greeted by a sign: BEWARE OF POLAR BEARS. After picking up some provisions, we set sail for our last American port, Prudhoe Bay. Upon arrival, we weren’t allowed to go ashore, but they did give us enough fuel to reach Herschel Island, Yukon.

It felt great to set foot in Canada again and explore the old abandoned whaling station, which had been turned into a tourist museum. As I tromped about the island, I discovered an old cemetery. Over many winters, the frost heaves had pushed up a casket and I could see the skull and some bones of a person simply named John—the name had been carved into an old weathered cross.

The sea was relatively ice free by the time we reached Tuktoyaktuk and while there, I met some fellow artists who were carving soapstone sculptures. It would have been nice to stay longer, but speed was a priority if we were to get through the Northwest Passage before winter arrived.

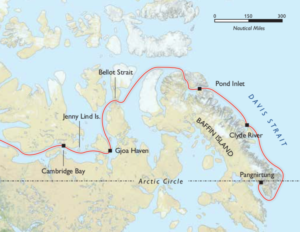

Upon arrival at Cambridge Bay, a friend of Winston’s, Chris Strube took us flying in his small plane to check out the ice conditions. The flight was quite exciting, especially when the plane suddenly swooped down over a herd of muskox. Because the ice had yet to break further east, we stayed for five days.

After motoring by Jenny Lind Island, another abandoned DEW Line station, we were forced to motor back. I had a lot of fun exploring the empty buildings and going inside the enormous parabolic aerial. Unfortunately, while climbing into the dinghy to row back to the boat, I had a misstep, which sent my video camera sliding across the back seat and into the sea! Like losing a lover, it almost broke my heart.

Heading towards Gjoa Haven, we were surprised by the lack of ice; it seemed to have mysteriously vanished! Once there, I met a renowned Inuit sculptor, Judas Ullulaq. Since he couldn’t speak English, his grandson translated our conversation and I was amazed that he was more interested in showing me his freezer full of frozen fish than talking about his art—such a humble man—a joy to meet.

Shortly after leaving Gjoa Haven we met up with the Croatian Tern, with Mladen Sutej at the helm. We rafted together and learned that they were planning to circumnavigate North and South America, which they eventually did. We were a little worried as we neared the infamous Bellot Strait located at the northern most tip of mainland North America. We motored through the narrow passage during slack tide and big bad Bellot Strait (which runs eight to nine knots and can change direction at any time) was on its best behaviour, so we didn’t have any problems.

On August 20, while Dove III sliced through a skim of ice, the realization that winter would soon be arriving began to sink in. And to top it off, we were introduced to a northwesterly full-blown gale reminiscent of the Bering Sea. When we finally reached Pond Inlet, the wind was blowing so hard, we had to bypass it in favour of Albert Harbour. When we were able to return to Pond Inlet, we anchored near a massive iceberg. When the berg began breaking up huge chunks of ice drifted toward our little boat—it was time to leave!

It was a long haul down Davis Strait to Labrador and when the wind picked up (combined with thick fog) the going became very dangerous, especially during the night. An iceberg could suddenly pop out of nowhere at any moment! Forced to tuck in at Clyde River, Baffin Island, we made friends with the local RCMP officer Jerry Smith and his wife Sandy who fixed us mouth-watering Belgian waffles. The boat was covered with a thin coating of ice when we left two days later. Winter pursued us like a hungry polar bear.

As we continued down Davis Strait, between the fog and stormy conditions, the situation became more perilous. Although 80 kilometres out of our way, Winston decided to head for Pangnirtung. Hoping for calmer weather when we returned to Davis Strait, we were instead greeted with the tail end of a hurricane, and with waves occasionally breaking over the entire boat, Winston decided to head back to Pangnirtung and leave Dove III there until spring.

While spending three days winterizing Dove III, we became good friends with Roy Bowket and his Inuit wife Annie. They were wonderful hosts who not only gave us an apartment to stay in, but also treated us to some great meals. I remember, after skidding Dove III ashore and securely tarping her, I looked back over my shoulder as we left and felt a touch of melancholy leaving behind my refuge from so many storms.

I recently saw a photo of Dove III, and after 25 years, she’s looking just about as beat up and old as me. Winston built another boat and at age 82 is still sailing around the BC Coast in the summers. George just remarried and is planning to get another boat. And me, never much of a sailor, I still have my dinghy from when I lived aboard Dreamer II. Maybe I’ll rig a sail on her and cruise around the nearby lake come summer. If I wait till the lake starts to freeze over, I can shut my eyes and imagine I’m once again aboard Dove III as she crunches through the ice of the Northwest Passage.