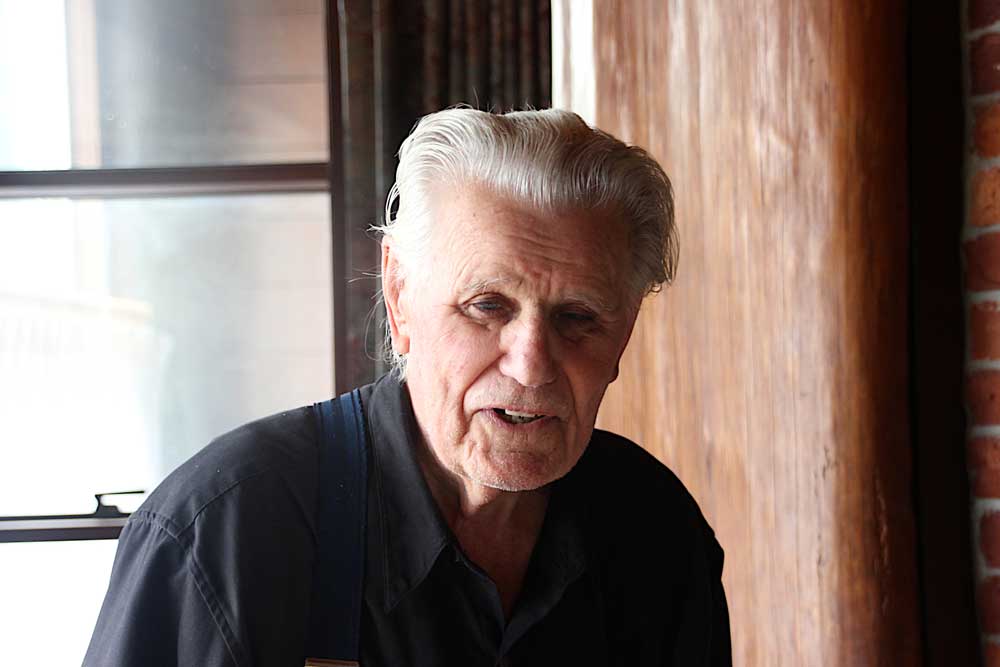

From the large, fir-framed windows in his Blind Channel home, Edgar Richter gazes out across the briskly flowing Mayne Passage toward East Thurlow Island. Trees in various stages of regrowth wrap the distant mountains; a sapphire haze covers a far peak with blotches of snow providing a blunt contrast. Near the house, other homes, cottages and a restaurant occupy a flat area, one of the rare level pieces of land in the Discovery Islands. West Thurlow’s Blind Channel Marina and Resort is the handiwork of this 90-year-old pioneer and his family. For the past 47 years, it’s been a work in progress.

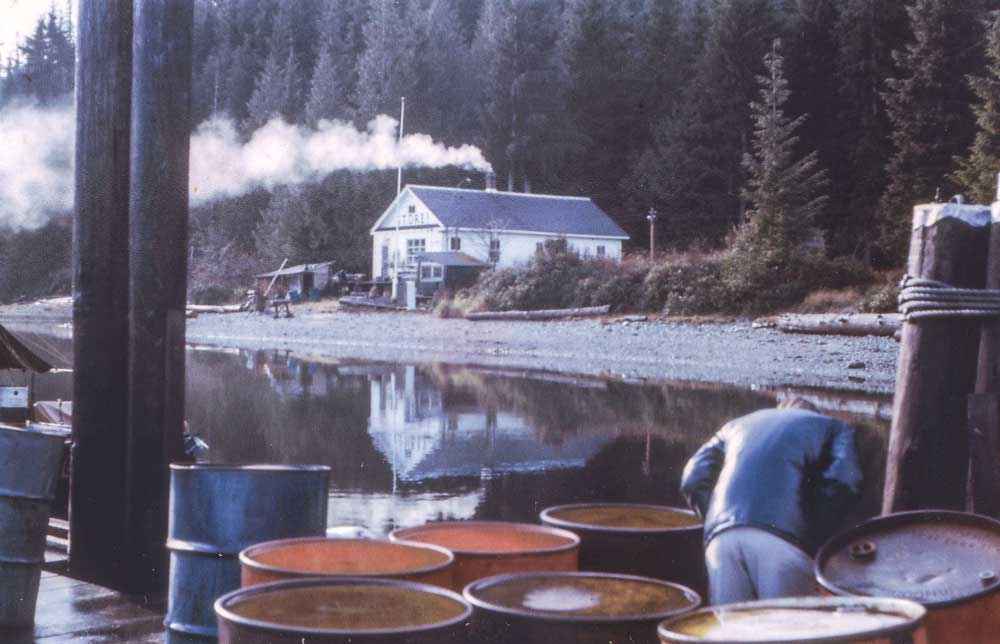

IT WAS 1969 when Edgar saw the for-sale sign at Blind Channel when he, his wife Annemarie and children Philip, Trudy, Alfred and Robert cruised north in his hand-built, 30-foot wooden boat, Pamar. Edgar was instantly smitten: it was the property he’d daydreamed about for two decades. Annemarie was less enthralled. She noted the debris left behind by a cannery, a saltery and a shingle factory. She saw the rickety docks with their barrels of fuel that needed a hand-pump to dispense their contents. She was less than enthusiastic about the decrepit store and the shacks strewn around the place.“ It took me more than a year to persuade Annemarie that building a marina here was a great opportunity,” says Edgar. “You see, I’d rebuilt our Vancouver home so that it was really special and she didn’t want to leave it. ”To sway her, Edgar hired a float-plane to fly over the site. “It was a glorious sunny day and the view from the air helped convince her just a bit.”

The Vancouver house was sold and the proceeds spent on the out-of-way hectares. “We moved into the tiny quarters behind the store,” says Edgar. “It was extremely primitive. The kids slept in the sheds or on the boat. We began cleaning the place up with a wheelbarrow, a pick and a shovel. There were container loads of old bottles. Metal junk. Old rotten stuff on the beach. We dug a hole and buried a lot of it where the patio is now. Hard, back- breaking work. People don’t know what it takes to build something like this place—some think we bought it readymade. The old-timers who lived in shacks around here had a bet we wouldn’t last a year. They’re all gone now, many of them died fairly young. Too much boozing, you know. I’ve outlived them all.”

It’s clear that fact leaves him truly gratified.

He recalls one mishap during that initial winter. “It was bitterly cold and the water pipes that came from the creek and ran under our living room had frozen and broken. The water kept seeping out and the ice pushed up a foot-high bump in the floor. We had walk around it.”

EDGAR WAS BORN near Munich in 1926. While a teenager, like all German youths, he was drafted into Hitler’s military machine.

He joined the Luftwaffe as an aircraft engine mechanic, saw no direct combat yet became a prisoner of war at the end of World War II.“I was in Salzburg and was luckily able to avoid the Russians. The Americans caught me. From Ulm, they transported prisoners to France’s labour camps. But I positioned myself at the back of the last truck in the convoy. I knew the area and in one especially curvy bend in the road, I jumped off and hid in the woods.” He found his way to his parents’ home, but without official papers, couldn’t seek employment. Eventually he turned himself in at an American prison camp, was detained and helped build fences for a camp that incarcerated SS officers. “It wasn’t bad. I knew how to fix their banged-up jeeps. We had food and cigarettes, much more than during the war. I got my papers after three months.”

In 1946, Edgar married Annemarie and became father to Trudy and Philip. But he yearned to leave Germany and had chosen Canada as his destination. “Germany had too much red tape. No freedom. I saw Canada as a big open country with few people. Annemarie thought South America was more romantic, but I wanted something bigger and held fast for Canada.” In 1952, he arrived in Montreal alone and made straight for Vancouver. “It was tough,” Edgar recalls. “I knew only ‘yes’ and ‘no,’ didn’t know anyone. I tried working in the aircraft industry but needed more English. ‘Come back in a year,’ they said. Of course, I couldn’t wait a year. So I relied on my other skill— woodworking.”

Annemarie and the children joined him six months later, while Edgar worked as a carpenter. Later, he became a supervisor at B.C. Airlines overhauling aircraft engines. He flew out to isolated camps to repair the engines on a Grumman Mallard or a de-Havilland Beaver and seeing B.C.’s vast archipelagos from the sky whetted his taste for closer-up exploration.

That’s when he began building boats, ending with a Frank Carius-designed pilothouse cruiser—the boat that brought the Richter family, now including four offspring, to Blind Channel. “I always wanted to leave the city,” says Edgar. “I’d built some houses in Vancouver. But I wanted to build here.”

SLOWLY THE FAMILY transformed the site. Edgar built a workshop and other structures. Fuel tanks and a generator were installed. To supplement the family diet, he fished and hunted. Annemarie, to ward off winter isolation, began creating her now famous mosaics incorporating broken glass bottles, shattered pottery and other found objects, selling them to yachties who came in ever increasing numbers. “It was slow, without a lot of revenue, but I was never discouraged,” Edgar says.

They built 36-metre docks—figuring they were the right size for two boats to line up (with yacht-size creep sometimes only one will fit). A gorgeous new house for the family was erected. I admired the beams buttressed by highly polished tree trunks, complete with sinuous burls and bumps. A big fir slab pivots to reveal a bar. Edgar hand-built the sturdy, European-style furniture. He proudly points out the fine-grained old-growth fir in the coffee table. The walls are lined with Annemarie’s paintings and mosaics— and a huge mosaic Edgar made himself.

“We started a restaurant in this house,” says Edgar. “Annemarie cooked traditional German dishes. We could seat 35 and it was a great success. People liked the homey atmosphere and they’d linger while other diners would sit on the staircase and lawn waiting to get in. The kids and I were the waiters. That led to our building the restaurant.”

TODAY, SON PHILIP and grandson Elliott manage Blind Channel’s enterprises, with the excellent restaurant, rental cottages, fuel dock, small grocery, marina and delivery services. A fourth generation has sprouted. Although she died in 2003, Annemarie’s artistry still adorns the premises. Edgar may be a nonagenarian, but he repeatedly tells me he’s not finished his life’s work. He’s retired from the daily business, but his head spins with ideas. A plan for an improved sewage system lies on his drafting table. He says he supervised the building of the cabins in 2016.“I have three buildings and three more cabins in my head. As soon as something’s finished, I must start again. Let me be clear. I’m waiting for the future, not the past.”