A glass fishing float drops into the waves in Japan; someone daydreams of feeding their family. In the night, a storm predicted to be smaller than its reality hits. A rope breaks, a dream is lost. The glass float travels across the pacific, it drifts past whales and bounces off rock; it weathers storms in unimaginable places. Eventually it rides the crest of a wave that gently lofts it onto a sandy remote beach leaving it stranded. On this remote shoreline across the Pacific it is found by someone that considers its beauty and keeps it as treasure.

Nothing is a finer treasure to find along our shores than the elusive glass ball. Dedicated beachcombers will drag home all kinds of flotsam but the coveted prize has always been these fragile glass orbs.

There isn’t anything particularly special about them when you think about it. They’re just fishing gear and at the time they were in their peak they were cheap fishing gear. What makes them special to us is the journey they’ve been through and the fact that against all odds they’ve made it across an entire ocean intact.

Many countries around the world have developed their own unique form of glass floats but the majority of floats found on the British Columbia coast originate from Japan and make their way to us riding the Kuroshio current.

Glass balls were used heavily for fishing in Japan during the mid 1900s. In 1948, four of the factories in Japan produced a total of 300,000 floats each month. During this period there were more people fishing for a living in Japan per capita than any other country in the world. Due to the technology of the time and the nature of glass, fishermen were suffering a 50 percent loss of their gear per trip. The balls were in high demand.

With the balls being lost at such a high rate the odds for them reaching us were pretty high. In the 1960s to the 1980s glass balls were still arriving in B.C. in high numbers. That was 30 years ago. Now plastic floats have flooded the market as a better choice for fishers and glass floats are no longer in production for the industry.

For beachcombers this means the odds of finding a glass ball are becoming increasingly rare. However, three years after the 2011 Japanese tsunami, a resurgence of glass balls started to show up on beaches along our coast. These were surmised to have been landlocked and then washed out to sea. Where they landed and for how long this will continue is anyone’s guess. The Kuroshio current or Black Tide does not always carry things in a direct path to us. Items can be slowed down by barnacles, caught in ocean gyres or circulate several times around the Pacific without reaching landfall. When we find glass balls now they are not only unique because of the odds they’ve beaten but because they are getting old; some of them traceable to over 100 years.

Markings

Many glass balls come with trademark stamps imprinted by their manufacturers and are traceable to their place of origin. This along with size, colour and texture gives collectors a way to gauge the value (most of it personal) of their beach-combed find.

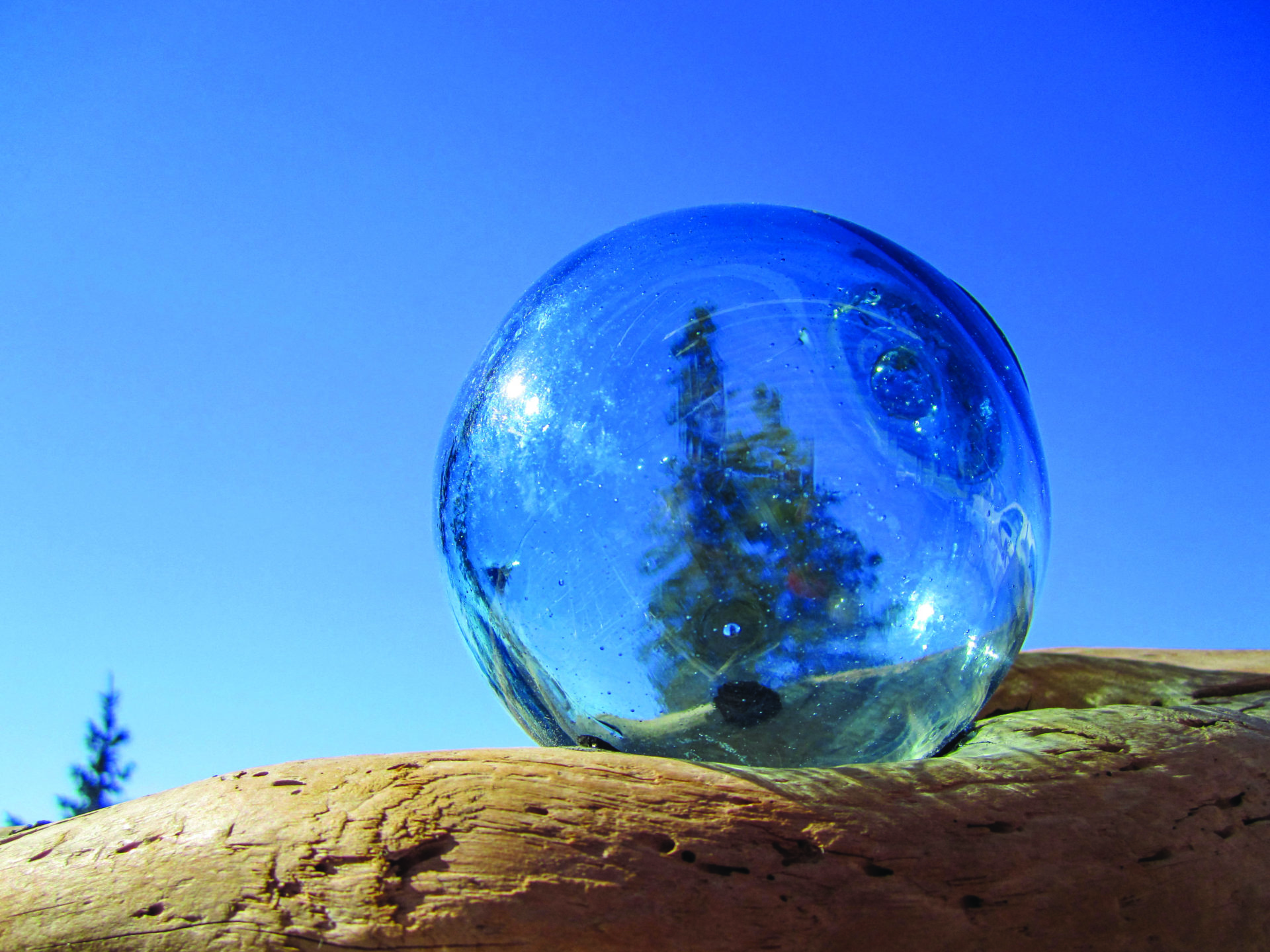

Typically glass floats coming from Japan are pale blue or green but the depth of colour varies. Some balls will have beautiful dark blue swirls embedded in the glass, some greens are pale and some are as dark as beer bottles. The rarest coloured balls to find are the pink/purple balls that were used exclusively by the emperor’s fishing fleet; but they are out there.

Balls with flaws also draw a lot of attention from collectors. Sometimes, while blowing a ball, there can be a spindle of glass left inside looking like a tornado forever locked in place or an extra bubble of glass will form on the inside of the button (the button is the closure that seals the ball) giving the appearance that there is a ball within a ball. Other eye-catching flaws for collectors are balls that show the effects of touring the ocean for years in the way they have been weather-worn in sand blasting storms. Or how they’ve been made into a travelling home by intrepid barnacles or taken in some water from being plunged into the deep.

How to Find them

Winter is the best time to search for glass balls. High winds backed by storm surges sweep around the ocean carrying debris from far away and throwing it onto the beaches during cold rainy gales. Conditions rearrange the shorelines and leave everything utterly exposed giving us a chance to actually see what’s out there before it all gets covered up by the shifting sands of summer.

Keep your eye on the weather further out in the ocean. It is almost the same science surfers use to predict big swell rolling in. If there is a big storm happening in the centre of the pacific being followed by a wind blowing on shore, chances are good that these conditions will be carrying marine debris.

There are always indicators on the tide line for good days to find glass balls. If you’re walking the beach and you start to find other glass objects, florescent light tubes and light bulbs or glass bottles, particularly saki bottles, glass balls are often around too. Velella, or blue sailor jellyfish are also a typical omen.

The balls can be anywhere. I’ve found balls glistening in the sunshine on a fresh tide line or tangled in a mass of floating kelp in a calm bay. I’ve found a large ball lying in a puddle among a minefield of barnacle-covered boulders and I’ve dug a ball barely visible right out of a sand dune. However, the most likely place to find them is walking in the highest tide lines through the driftwood. Any debris lighter than wood is naturally trapped behind the logs when the water retreats. No two balls are alike and no two balls are ever in the exact same place.

I’m not going to give away my “secret spots,” but I will say that I’ve found all my glass treasures on the remote beaches of Haida Gwaii. The archipelago is completely exposed to the Kuroshio Current and prevailing westerly swells that carry debris across the ocean. The beaches in this area are remote and very difficult to reach especially in the winter months. The winds are strong, and pulsing swells are ever present on the west side. We’ve found that cautiously and with a lot of local knowledge we can put ourselves in the right place at the right time. From talking with other glass ball enthusiasts while cruising the north coast I can say that the chances of finding balls along the beaches on the west side of Vancouver Island and the east side of Hecate Strait are also fairly high.

In the end, looking for glass balls is all about chance. I could divulge to you every single intimate detail I know about finding glass balls and try to put you in the exact right moment and still you might not find one. They are tossed by the whims of the ocean and she is random with her organizational skills.

Finding a glass ball has never lost its excitement for me. From the very first ball I found to my 100th my heart still skips a beat, and to this day I’ll still find myself on a beach without another human being in sight for miles but when I see a glass ball I’ll run for it full speed, tripping over logs and slipping on kelp to grab hold of its magic before anyone else can.

The offseason can be a difficult time for cruising. It’s wet and fiercely cold, the darkness limits our days drastically, the winds become stronger and everything just becomes super challenging. Looking for glass balls is an excellent way to hone your winter cruising skills and maybe, just maybe you’ll find a special reward for your effort.

Types of Balls