“She is not only the oldest sailboat, but is the most beautiful boat on this coast,” wrote G. W. Burnett, about the little racing sloop he had owned in the 1950s. “Take care of her, please,” he implored in a letter to David Baker.

The year was 1985. Baker, a Victoria-based physician, had bought Dorothy a year before and was preparing the 90-year-old wooden gaff-rigged cutter for Expo ’86. In acquiring Dorothy, Baker had stepped into a distinguished lineage of boat lovers wooed by her sensuous design—“the most glorious lines possible”—and exquisite handling on the water. And like those before him, he became nearly obsessed with restoring Dorothy to the point where she once again shone as she did 100 years earlier.

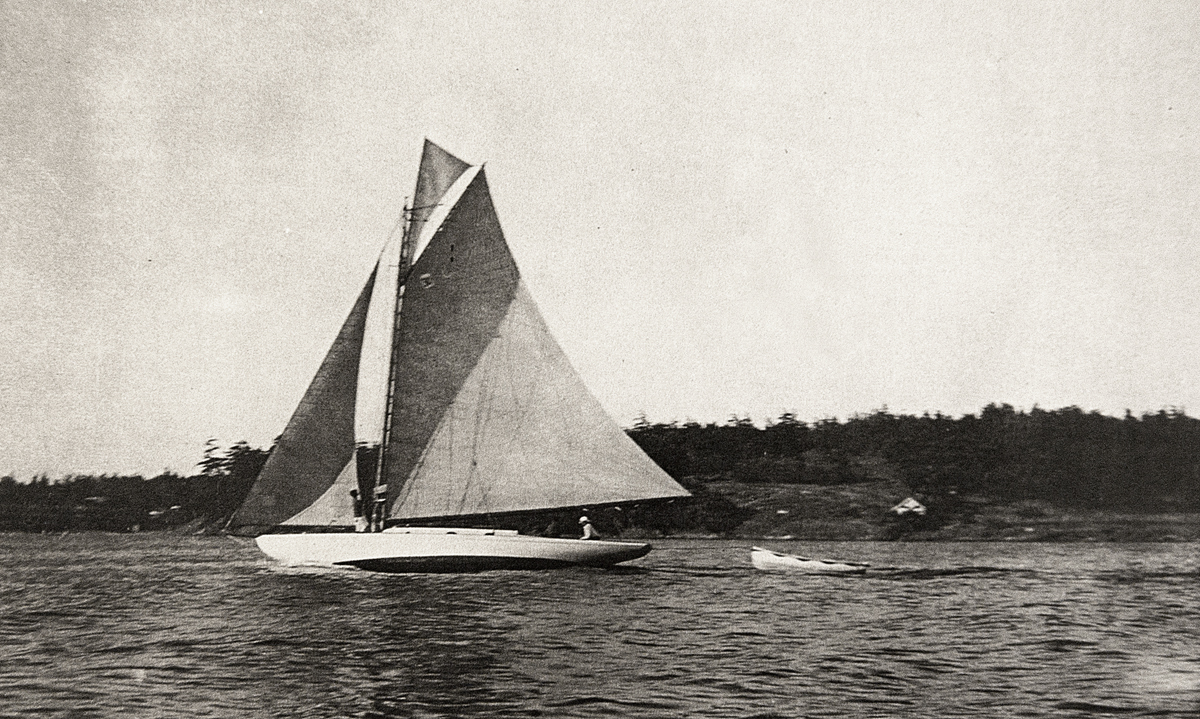

In over a century of sailing the West Coast, the wooden sloop with the distinctive fantail built along European lines excited attention wherever she went. Experiencing dramatic swings of care and neglect over the years, Dorothy was repeatedly resurrected from the brink of decay, likely because of her beauty.

“She is pretty, which is key to boat survival,” says John West, a trustee for the B.C. Maritime Museum, which owns Dorothy as part of their small fleet. “She was built well in the first place and looks oddly light, but she really is massively built. There’s lots more material in her than it appears, and she’s made from probably the best choice of boatbuilding wood in the world, first growth cedar.”

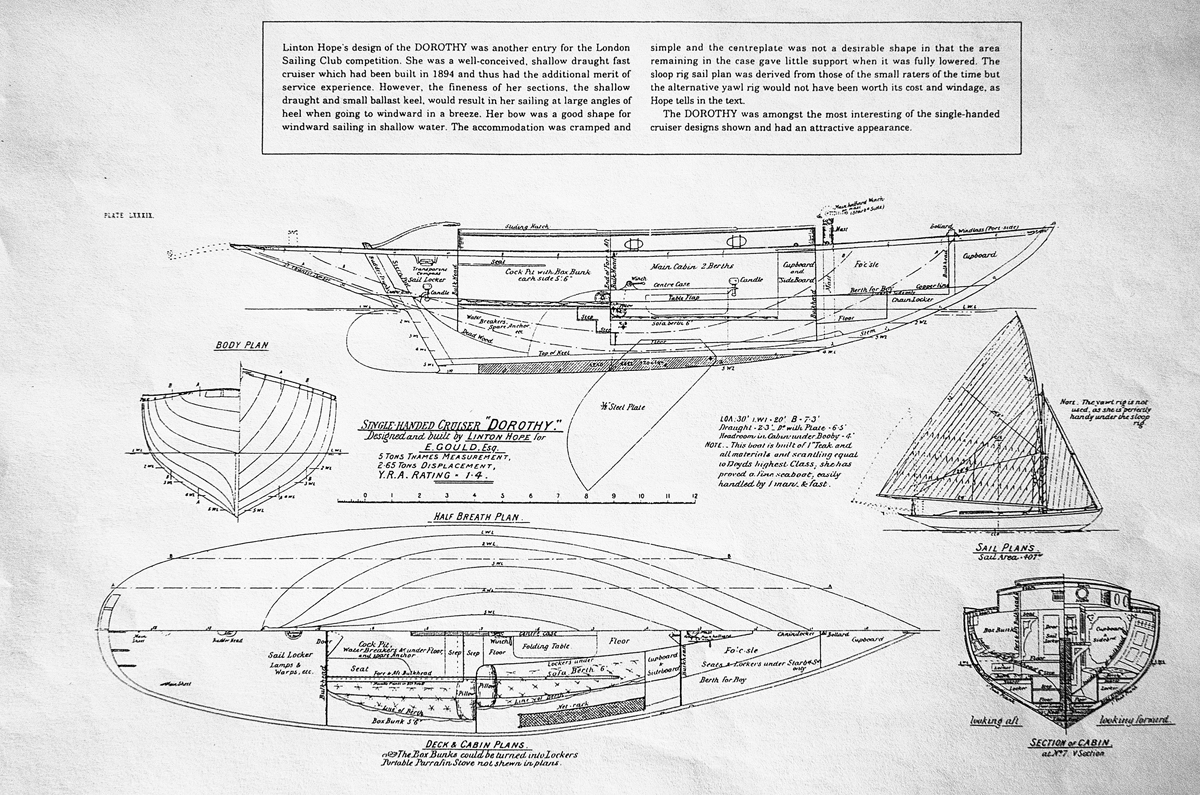

A Victorian Past Dorothy was conceived and commissioned by W.H. Langley, a Victoria barrister and Clerk of the B.C. Legislature, who wanted a fast boat to race his contemporaries at the newly formed Victoria Yacht Club. He wrote England’s pre-eminent yacht designer Linton Hope for plans, and over a year of friendly correspondence, acquired the design for a single-masted sloop cutter. John J. Robinson built Dorothy I in his James Bay Boatyard on Montreal Street for around $1,700.

Chuck Charlesworth, an architect from Victoria who owned Dorothy from 1964 to 1973, describes Langley as “an unusually exact and meticulous man” in his unpublished book Dorothy I—A Sailor’s Legacy. Langley “carefully documented all stages of construction… The remarkable records which Langley kept indicate that he had originally considered having Dorothy built in England.”

Langley was delighted with his “fast little ship” and raced her to many first place wins with the yacht club. With the onset of the First World War, Langley put a manager in charge of Dorothy and went to serve in the Navy. It was apparently one of the hardest things he ever did. “During the Great War, the Dorothy was not used by the owner,” Langley wrote in his log, following his habit of referring to himself in the third person. “In the winter of 1915-1916 he paid a visit to her at her moorings and did not see her again until his return in April 1918.” He was appalled at her condition. “The first man in whose care she was left apparently did not understand boats or hadn’t time to look after her. She was sadly neglected.” (from A Century of Sailing, by Terry Reksten)

Langley’s meticulously-kept logbooks, preserved by the MMBC, give an intimate account of races, regattas in Victoria, Cowichan Bay, Port Townsend and Vancouver, leisurely day sails and comical groundings aboard his beloved boat, often accompanied by detailed sketches of favourite anchorages and treacherous spots. He sailed her for almost 50 years before selling her to Robert Saver in 1944, when she was finally entered in New Westminister’s Ship’s Registrar.

Ups and Downs Over the next 20 years, as she was bought and sold four more times, Dorothy’s level of care apparently suffered. Vandals broke in and set fire to her under Burnett’s ownership: “The fireboat saved her but the cabin (top), cockpit and engine were gone,” wrote Burnett. When Chuck and Pam Charlesworth found her in 1964, Dorothy was “resting like a proud swan in a marina in North Vancouver,” moored alongside a partly submerged wharf attached to what appeared to be an abandoned warehouse. They bought her “more with our hearts than our heads.”

She was undoubtedly saved by their ignorance of her true condition. “We were so taken with Dorothy’s appearance and her lovely lines that we didn’t want to delve too deeply when on the lookout for trouble,” confessed Charlesworth. Once hauled out, they found a badly repaired and patched plank below the waterline. “If the damaged section had remained unattended for even a short while longer, the patch would have completely disintegrated and the boat would have sunk.” Dorothy had just escaped her second brush with certain destruction.

Over the next nine years, it appears Dorothy was out of the water more often than in. Charlesworths replaced three or four planks, fixed the damage to the cockpit and cabin, and uncovered a cloth stuffed in the bilge that had caused some rot. But when they did sail her, they were surprised to find what a fast little boat she was.

“One day while out under full sail, another boat somewhat larger than Dorothy sailed along and the boat’s skipper suggested we try a short race… To our surprise Dorothy not only kept up, but after a while pulled ahead of our opponent. Eventually we headed up wind and allowed the other boat to catch up.” Charlesworth was later to learn that not only had Dorothy won many races, but they had done exactly what her original owner Langley had done on many an afternoon, “challenge any skipper who wanted to take him on.”

This impulse to race also inspired Dorothy’s two subsequent owners, Angus Matthews (1973-1984) and David Baker (1984-1991). Baker confessed to sneaking up on a larger yacht and innocently racing without warning, then being thoroughly disgusted when the other skipper would drop sails and sheer off when Dorothy pulled ahead, “as if they didn’t know what was going on.” Matthews took such pride in how she sailed, he refused to use her engine: “Elegance and grace, she’s the perfect combination of that formal, classic style. And she was fast too. I raced everybody, whether they knew it or not.”

Continuing the legacy of care begun by the Charlesworths, Matthews and then Baker worked diligently to rebuild Dorothy. Baker learned traditional steel wire splicing, parcelling and serving in order to re-rig her authentically. He and his partner Su Russell replaced all of the running rigging, re-built the mast and boom, had a new forehatch built, added winches for safety and sailing efficiency, and had Bent Jesperson make a new rudder and tiller.

After years of family sailing—sometimes packing as many as six bodies into her tiny cabin for weekend sails—Baker sold Dorothy to Kim Pullen, owner of the Port Sidney Marina. Pullen commissioned a full refit from Hugh Campbell and then donated her to the B.C. Maritime Museum in 1995, just two year’s shy of her 100th anniversary.

A Mobile Exhibit Dorothy is the only “mobile exhibit” in the MMBC’s little fleet, which includes Trekka and Tillicum. The Museum proudly sailed her until 2003, but, lacking funds and direction they put Dorothy into storage in 2003, where she was largely forgotten and languished unseen by the public for nine years.

Hidden away in storage is where Tony Grove first saw her in 2011. The boatbuilder and artist was working on Trekka (of “Round-the-world” fame) for the MMBC at the SALTS workshop in Victoria when he was asked by someone affiliated with the Museum to give Dorothy a once over for an opinion on her condition.

“I was intrigued by her dated design and her beautiful fan tail. After climbing through her, my gut feeling was ‘she seems to be in pretty good shape’ especially considering her age. I was shocked to find out that a recent survey had condemned her, concluding she was not worth repairing. I have seen many a ship in far worse condition brought back from the brink, and in my opinion it would be almost a crime to let her go.”

As a shipwright and self-confessed “boat geek,” Grove has been building and restoring boats of all kinds since 1980. Post apprenticeship, he specialized in wooden boat restoration and interior boat building. He has taught boatbuilding and boat interior construction at a number of schools, including the Silva Bay Boat School (now-closed), and Great Lakes Boatbuilding School in Michigan, and he continues to develop boatbuilding curriculum. He lectures at Port Townsend Wooden Boat festival and is a regular judge at Victoria’s Classic Boat Festival. Grove now works for himself as a custom woodworker, boatbuilder and artist at his home shop tucked amongst the trees on Gabriola Island.

A New Lease on Life Dorothy made the trek to Grove’s shop in the summer of 2012, and in December of that year he began an exploration of her condition. Finding little to be deeply concerned about beyond the typical issues faced by an elderly wooden boat, Grove presented two options to the MMBC trustees for her refit. The first, and the cheapest, would be “to put Dorothy back together with some new wood where needed, floor timbers and some deliberate caulking below the waterline.” This would allow her to sail away safely but would necessitate redoing her again in a few years, or at least having to deal with ongoing maintenance.

The second option, the one the trustees ultimately decided on, was “to wood the hull, reef all the seams, repair any planking or damage, put in new floor timbers, refasten where possible and re-caulk her whole hull, addressing all the age-born ailments.” Grove would need to strongly support the stem and stern while doing the repairs to minimize and correct any hogging (the natural slouching of the wood that occurs over time). And that, hopefully, “will give her a new lease on life,” says Grove.

As a wooden boat, Dorothy still carries the energy from cedar logs felled from virgin West Coast rainforest. The mass of correspondence, logbooks and images that have been collected around Dorothy are a direct link to the earliest colonizers of British Columbia, with their fears about war, grief over loss, and joys in the simple act of sailing and exploring the coast. She is a living embodiment of the hopes, sacrifice, love and lives of everyone who poured time and energy into her over the past century, and even now, a troop of ordinary heroes gathers to restore her yet again—again, against the odds—to immortalize themselves in the greater story of Dorothy.

By Tobi Elliott and Tony Grove