During our 25 years of sailing in waters far away from the BC coast we always wondered how Haida Gwaii—and the Gwaii Haanas area in particular—might be changing. If we returned would we feel the same “magic” we so much enjoyed in years past? This past summer we had the opportunity to find out.

We first sailed among “The Misty Isles” in 1980. Then they were still named the Queen Charlotte Islands, affectionately referred to as “the Galapagos of the Pacific Northwest.” This was a wild, remote and challenging environment where boaters had to arrive prepared, both mentally and physically. One had to be self-sufficient, ready to cope with often harsh, rapidly changing conditions, and equipped to make repairs without assistance. It helped to have a positive attitude, to quickly adapt to the vagaries of weather, to consider inconveniences as adventures, to anticipate adversity and to embrace serendipity.

We—among others—pioneered sailboat-based eco-adventures in the area. While each summer season started and ended with an exploration of the mainland coast, the four or five months in between were spent in Haida Gwaii. During a dozen full seasons we gained an intimate understanding of the place. Our trips were eight to 10-day adventures either along the east coast between Sandspit and Cape St James, or through Skidegate Narrows and down the west coast. A few times we circumnavigated Graham Island. We engaged enthusiastic people to share their knowledge of nature or culture. In turn, these specialists attracted guests who were keen to learn and hungry for experiences in the wilderness.

In the early years we explored dozens of sites with huge midden mounds but scant cedar remains—as well as the more obvious villages like Skedans, Tanuu, and Ninstints—which showed the greatness that once was. Ninstints on SGgang Gwaay was then a restricted Class A Provincial Park (not yet a UN World Heritage site), and was a silent, haunting village with more poles and house remains than any of the others.

In the 1980s there were few visitors. At most we would see some commercial fishermen (both Haida and otherwise), and several residents at the abandoned whaling station of Rose Harbour. Among the Haida some individuals stood out for us. Wanagan was actively pushing for preservation and spent summers camped on SGgang Gwaay, Bill Reid was as passionate about stopping the destruction of the land as he was about art, and his young friend and student Guujaaw, was a carver, hunter, drummer and singer, who became an active voice for the Haida. Guujaaw was later elected President of the Haida Nation, and recently named Gidansda, hereditary chief of Skedans.

THE HAIDA HAVE always attributed their cultural uniqueness and strength to natural abundance in the seas and on the land, but large clear-cuts were rapidly transforming the unique old growth forests. Telunkwan Island, which had been devastated by logging, became the focus for an international campaign to protect the wilderness. John Broadhead of the Island’s Protection Society, Thom Henley, who ran the Rediscovery Program on Graham Island, Paul George of the Western Canada Wilderness Committee, and Guujaaw—along with an increasing number of Haida people—began to stand up to the big logging companies, and to a very complicit provincial government. CBC’s “The Nature of Things” did a feature called “Which Way Windy Bay” which helped to elevate South Moresby from a provincial concern to a national issue. Walking in old growth forests fuelled in visitors an overwhelming sense of urgency to stand with the environmentalists and the Haida in support of preservation. After seeing the extent of the clear-cuts many of our guests became actively involved in the politics of preservation. Later, the Haida organized blockades and protests, which included the arrests of several elders. This in turn brought federal government pressure on the province to end the logging. In 1988 Parks Canada entered into a partnership with the Haida to create the Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site.

The visitor today reaps the benefit of the efforts of many to preserve a special part of nature. That fight is well documented in: Ian Gill’s: All That We Say Is Ours, or Elizabeth May’s: Paradise Won, the Struggle for South Moresby.

By 1991 we were confident in the conservation of Gwaii Haanas, soon to be the first co-managed national park in Canada, and we set sail for distant shore. We continued to guide adventures using the same format in coastal environments around the world and many of our past guests joined us along the way. Haida Gwaii was inevitably part of our conversations.

The next 10 years went in a flash. We eventually sold our Ocean 71 Darwin Sound and bought a Dufour 45, which we also named Darwin Sound. Another 15 years flashed by and it was not until last year—after crossing the Atlantic once again—that we sold our Dufour and returned home, boat-less.

AFTER 26 YEARS—and thanks to friends who kindly loaned us their boat—we sailed back to Haida Gwaii last summer. Any time you re-visit a place there is some trepidation. We wondered if the islands would still be the magical place we loved and remembered. Would our experience be hampered by park restrictions, by too many other visitors, or perhaps by development? Sailing into Skidegate Inlet we were excited to see new poles had been raised in front of Skidegate village, and yet more on the beach in front of the museum, which had also changed to include multiple buildings plus a carving shed humming with activity. Skidegate now clearly illustrates the success of the Haida resurgence.

After provisioning, catching up with friends, and visiting the much-expanded museum (and art galleries too) we set sail from Sandspit to Skedans, south toward the wilderness we so fondly remembered. It wasn’t high season yet we saw no other boats during our sail that first day, and very few in the days to come. Even with growing popularity, a limited daily quota for park visitors serves to ensure the area will not feel crowded. We met more kayakers than sailors and saw only a couple of charter vessels.

MOST VISITORS TO Gwaii Haanas restrict their journey to the east coast, where myriad inlets and bays allow for relatively calm sea conditions and protection can be found in any weather. However, during a high-pressure system with steady northwest winds sailors can enjoy excellent blue water sailing along the west coast (in depths of 1000 to 2000 metres) and many secure anchorages. There are still very few navigation aides in the islands, but in our experience the paper charts are accurate. The same water hole off Darwin Sound still offers a good source of clean drinking water, but with an improved dock. The cumbersome Fisheries and Oceans mooring buoys are gone, but some sites now offer visitor buoys for short stays. A couple of National Parks cabins have been built, and old squatters’ huts have been removed. In the south, Rose Harbour has not changed much, and is still a bit of a social centre, offering simple accommodation and meals for visitors. SGgang Gwaay was busy, but Watchmen ensured our visit would be tranquil by limiting the number of visitors on shore at the same time.

During many of our shore walks we relied on our memories and instincts to guide us. Our hike up into the San Cristobal Mountains was just as tough and rewarding as ever, and still without established trails. The underlying policy is to make it possible for a person to feel that they are among the few to have walked there.

The old village sites felt just as powerful to us as before. The carved poles and cedar planks have aged as they continue to serve as nurse wood for new growth, but a strong sense of place remains. Ninstints is still haunting, as well an outstanding exemplar of Haida wealth. Haida Gwaii Watchmen now preside over half a dozen of the main sites. They are the next generation, picking up Haida language, learning songs and dances, proud to be Haida and sharing their stories. We found them to be welcoming and friendly, engaging and well informed.

THE FORESTS THANKFULLY remain untouched. For many this brings an awareness that they have never seen an intact old growth rainforest. Most visit Windy Bay on Lyell Island, where David Suzuki filmed “Which Way Windy Bay” in 1984. A longhouse was built in Windy Bay during the fight to stop logging on Lyell Island, and a pole was raised in 2013 to commemorate the cooperation and co-management of Gwaii Haanas. Once onshore, visitors are greeted by resident Watchmen, then take the same quiet walk through the open forest floor which we so enjoyed during the 1980s. The giant Sitka spruce, so large that it takes a dozen people arm in arm to surround it, is still standing, and admired. Windy Bay is just one of many old growth forests in Gwaii Haanas. You could anchor in Poole Inlet on Burnaby Island or in Bag Harbour or Carpenter Bay, and feel the magic of equally magnificent old growth.

If you heard about the 2012 earthquake that disrupted the flow of hot water at Hot Springs Island don’t be dismayed. The hot pools are in better shape than ever. Watchmen look after this site too, offering hot showers to aid in keeping the various rock pools clean.

WE USED TO explore Burnaby Narrows at low tide, the rich inter-tidal area Bill Reid called the world’s longest sushi bar. Thanks to Gwaii Haanas management, visitors must now float over at high tide, and can no longer compromise the organisms by walking on them, or by collecting them. There are restrictions on transiting the narrows too. These positive changes and others can hopefully protect the rich abundance in this unique ecosystem.

This year we saw cetaceans, including humpbacks, greys, orcas and large pods of Dall’s porpoises and Pacific white-sided dolphins—frequently.

HAIDA GWAII WAS was and is known for its huge sea bird colonies: Ancient murrelets, storm petrels, auklets, puffins, and shearwaters, are among the many species that come to nest on these off-shore islands. Seabirds too are threatened by over-harvesting too far up the food chain, and since many are ground nesters, by rats, and raccoons. Avid birdwatchers are advised to visit from March to June, during the nesting season.

A trip around Cape St James will bring the hardy yachts-person by the largest sea lion colony on our coast, and just possibly to the group of resident orca whales that feed on seals and sea lions. The boisterous waters around the cape support puffins, murres and other sea birds, and is a place where one can often see black footed albatross. After the rather rough ride we recommend a stop at the long sandy beach at Woodruff Bay, a place we used to call Hawaii Beach.

WITHOUT A DOUBT our re-discovery of Haida Gwaii was positive in every way, and reassuring. We could still wander freely among ancient cedars, listen to Raven calling, sit quietly on a mossy hummock below a carved cedar, clamber ashore on a deserted beach, and anchor alone surrounded by nature.

Culture, song and dance honour the old ways, and encourage fresh creativity among younger Haida. There is a renewed sense of pride in their communities. Our first journey to Haida Gwaii in 1980 inspired us, but also ignited some concern about how something might be lost through increased impact and exploitation. Now, over 35 years later, it still is a wild, remote and challenging environment. We are confident that with continued vigilance the magic and sense of wonder will endure.

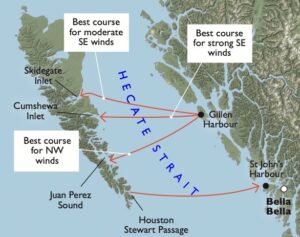

Hecate Strait is considered to be one of the most dangerous bodies of water in the world. The strait is relatively shallow, with reefs extending off much of the mainland coast, and Rose Spit is no place to have on your lee so wait for settled conditions before crossing. We prefer to sail across in moderate winds and we plan for a daylight passage. Although we have crossed between the northern tip of Vancouver Island and the southern tip of Haida Gwaii, we do not recommend this longer passage. We suggest the shorter distance between the mid-coast (north of Bella Bella) and the central part of Gwaii Haanas (Juan Perez Sound). Our favourite route is to cross from Gillen Harbour and return to St John’s Harbour. A return trip in strong northwest winds can be pure magic.

The Gwaii Haanas trip planner has a list of charter companies that can take you through the islands by sailboat, motor vessel or kayak.