Turning left from Queens Reach in Jervis Inlet and heading past the Young Life summer camp at Malibu Club, the water bubbled around us. We’d timed our run through Malibu Rapids for slack water, but the sea never grows completely still here and we kept a sharp eye out for logs and other debris washed loose by heavy summer rains.

Slowly motoring out of the rapids and into the deep fjord known as swíwelát by the shíshálh (Sechelt) Nation, has always felt a bit magical. But sailing into Princess Louisa Inlet felt more significant this time. As the granite cliffs closed around Honey Bee, our Barnet Sailing Co-op Catalina 27, and the mossy forests dampened the chatter of surrounding waterfalls, I felt something close to reverence.

As we motored deeper into the inlet, dusk began to take hold. In the distance I could see that the dock at the head of the inlet looked busy, but the four moorings off of MacDonald Island were empty. We tied off to one just as the final sunset glow left the sky. Then we settled in for a calm and silent night.

From time immemorial, swíwelát has been of unique importance to the shíshálh people. Recognized as a sacred place in the shíshálh Nation land use plan for “its overwhelming beauty, mystical nature and spiritual character,” the inlet is home to a former village, burial sites and pictographs. It’s also the location of tah-kay-wah’-lah-klash, a mythical water horse that can be seen in the rock on the cliff face above Chatterbox Falls.

As the region’s caretakers, the shíshálh managed the area for thousands of years; utilizing a productive crab site and travelling through the forests to hunt for deer, black bears, grizzly bears and mountain goats.

With colonization, much of the shíshálh territory was developed without their consent. swíwelát was gradually divided up between outside owners—with the head of the inlet, the old village site, going to a man named James MacDonald. MacDonald reportedly bought the property from the BC government in 1927 for $420 with a mining windfall. An aircraft entrepreneur named Tom Hamilton bought the remainder of the inlet, 3,796 hectares of the Sechelt Reserve, from the Canadian Government for $6,000.

Fortunately for those of us who came later, MacDonald loved the site. Once there, he was a gracious host who loved entertaining the boaters, loggers, trappers and fishermen who found their way to the inlet. Later, when his money ran short and he could no longer afford to maintain the docks and trails he’d built, he rejected a hotel company’s offer of $400,000 for his cabin and land, and instead gave the property to the people of the Pacific Northwest.

“It is Yosemite Valley, the fjords of Norway and many other places all wrought into the background of our conifer forests,” he wrote at the time. “It should never have belonged to one individual.”

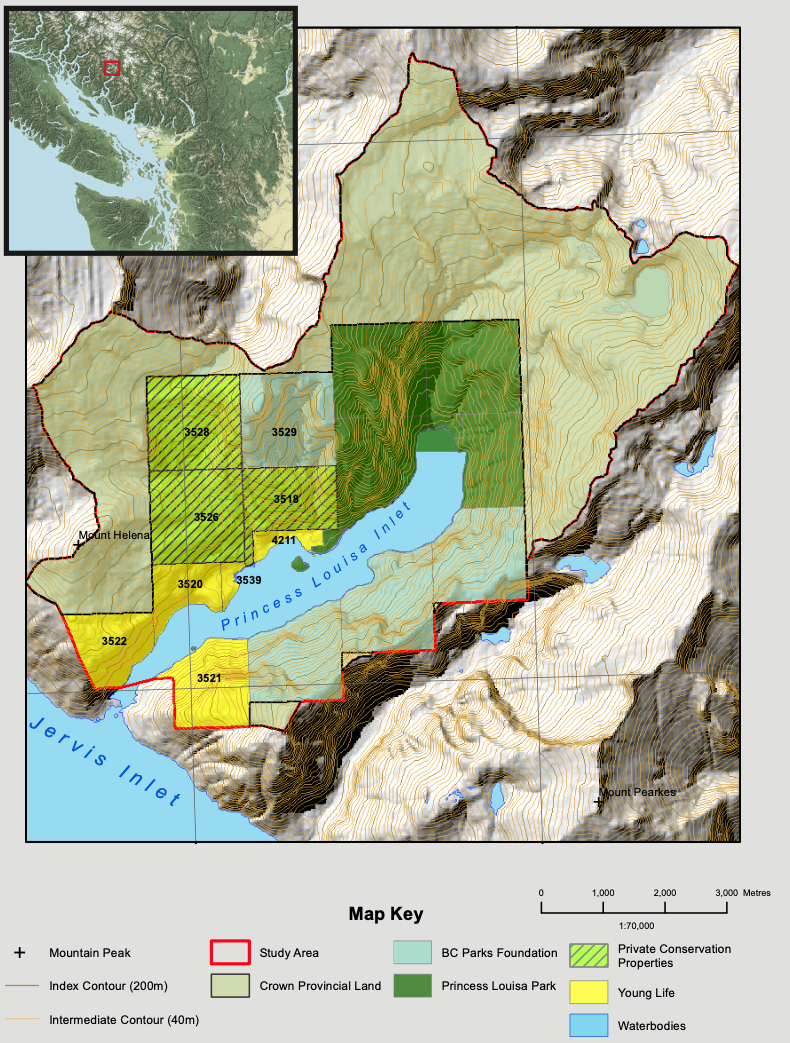

MacDonald’s gift of 18.2 hectares kicked off a conservation project that saw the inlet become a Marine Provincial Park in 1964. While Hamilton had sold off most of his land to MacMillan Bloedel as tree farm #19, a second acquisition added the islands that had belonged to Hamilton in 1972. A third acquisition added the 890 hectares upland of MacDonald’s original donation in 2003.

Princess Louisa Inlet’s pristine land and seascape is a must-visit for West Coast boaters. With multiple mooring buoys, a dinghy dock, the long main dock and a variety of hiking trails, campsites and picnicking areas—the whole inlet feels like a park. But what many visitors to the gorgeous inlet don’t realize is that despite the inlet’s limited development, only a portion of the fjord has ever been protected.

This was something Mel Turner, a volunteer on the Elders Council for Parks in BC, thought a lot about after his retirement from BC Parks. He’d spent a good portion of his 30 years with Parks working on ways to permanently conserve Princess Louisa, but was never completely successful. In early 2019 he noticed an ad in the Vancouver Sun. Three pieces of land totaling some 722 hectares, or almost the entire southern shoreline up to the mountain peaks, were up for sale.

While the heavily timbered slopes garnered interest from at least one forestry company, the Elders Council for Parks in BC, the Princess Louisa International Society, the newly formed BC Parks Foundation and the shíshálh Nation saw the sale as the stroke of luck they’d been hoping for: A chance to acquire and preserve a fourth section of the inlet.

In March 2019, the Foundation started discussions with a representative for the landowners, and by May they came to a purchase agreement. So in June, the foundation turned to the public with a bold goal: to raise the $3 million purchase price by the end of August, 2019. They wanted to buy the land and put it into joint management between the province and the shíshálh Nation.

It was the first week in September when we made our trip into the inlet. On the first morning I woke to vigorous sounding splashes. A couple of river otters were playing nearby, while a raven squawked from the woods. Across the inlet, mist was hanging in the trees and the sun was just beginning to touch the peaks. As I sipped my coffee, the inlet continued to come alive.

News had just come that the total funds for the land had been raised and the purchase was going through. “Look what $3 million bought you,” I said to the otters as they raced each other across the foreshore and disappeared out of sight.

After breakfast we rowed to the dinghy dock on shore across from MacDonald Island. Following a loop trail, we wandered through the forest until we reached a beach that looked across at the land that close to 2,000 individuals from places across Canada, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, China, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand and the United States joined local boaters in protecting.

Like many who donated, I felt pride in our combined accomplishment. Crowdsourcing has become a powerful tool in conservation—but the monetary amount, and short timeframe involved in buying the 722 hectares was unprecedented. Though it wasn’t surprising to Dr. Andrew Day, chief executive officer of the BC Parks Foundation who wrote PY, “Princess Louisa Inlet is an absolutely jaw-dropping jewel—anyone who visits there is touched by it. Plus, it’s in British Columbia, where parks are core to our identity. They are what make BC ‘supernatural’ and the reason why so many of us live here and visit.”

It was after we returned home from our trip to Princess Louisa, and were settling into the habits of winter, that I learned there are still three owners with unprotected foreshore and upland in the fjord. There’s the owner of the Young Life Camp; there’s the province, which currently controls the perimeter shíshálh ancestral territory as crown land; and there’s an unnamed private owner who holds three properties totaling about 800 hectares. What this means, Turner says, is that for boaters who love the fjord, our work isn’t quite done.

Crowd funding another $3 million likely isn’t in the cards right now. But seeing the project through to the point where swíwelát is protected for perpetuity means that the Elders Council for Parks in BC, the Princess Louisa International Society, the BC Parks Foundation and the shíshálh Nation are still actively working toward the future.

Turner explains that their wish list will take money. There’s the hope that the outstanding property might eventually be bought or the owner will add a conservation covenant. The land will also need a management agency—to regulate speed on the water and any future park development on shore. The greatest hope though is that a partnership between the province and the shíshálh Nation will result in a Watchmen program similar to the one on the North Coast and at Haida Gwaii.

Before European contact the land was already being protected, Turner was told at recent meetings with the shíshálh Nation. And, after being shut out of the conversations about their land for the past 150 years, it’s a stroke of beautiful luck the shíshálh will once again take their rightful place as the caretakers of a nearly unchanged swíwelát.