There’s a whimsical question that boaters ask each other in spring while working on the list of vessel chores: “Where are you going this summer?”

“North,” we would always say. This might mean to Kanish Bay or Cameleon Harbour or, better still, past Chatham Point to view the dark blue waters of Johnstone Strait stretching westward for over 50 miles. It’s a sight we’ve been drawn to for decades. When traversing this major route of the Inside Passage, we’ve seen vessels of all sizes—from cruise ships to kayaks—and the strait’s salmon-rich waters attract an abundance of marine mammals, including killer whales and sea lions.

Timing is everything when planning a voyage along this strait. Northwesterly winds often funnel down its 54-mile length in summer and “gale warning in effect” is a common refrain on the marine weather broadcasts. To avoid the predominant afternoon westerlies, most northbound boaters transit the strait in the morning, before the wind kicks up. If you’re underway by 06:00 hours, you can usually make good time.

Currents are another factor in Johnstone Strait, its deep waters in continual motion and always cold, causing frequent fog in summer when warm air comes in contact with its frigid surface. Flood currents flow east and ebb currents flow west in Johnstone Strait, but their speed and times of turn can vary considerably from one side of the channel to the other, with surface waters temporarily flowing in opposite directions depending on the state of the tide.

Flood currents are strongest on the Vancouver Island side of the strait, and ebb currents are strongest along the mainland side where estuarine currents, fed by freshwater runoff, contribute to the strait’s dominant ebb currents. Slow-moving boats should keep well to starboard when travelling in either direction, taking advantage of this ebb current when heading west and staying out of its path when heading east.

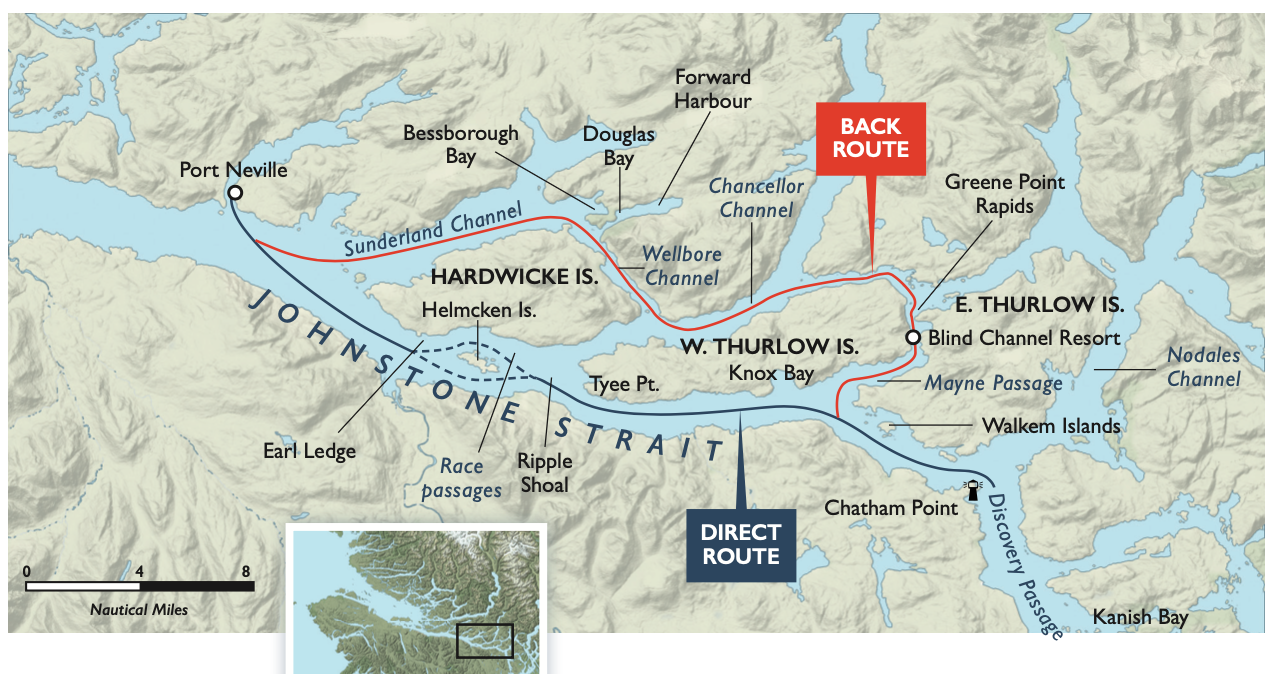

Understandably wary of Johnstone Strait’s challenges, many northbound boaters will avoid it for as long as possible, taking the “back route” of channels and passes skirting the mainland before rejoining the strait via Sunderland Channel. But if wind and tide are with you, Johnstone Strait is not only the most direct route north, it is scenic on a grand scale. A series of mountain ranges and ridges line the Vancouver Island coastline, their forested lower slopes rising to rugged peaks where patches of snow cling to granite crowns.

The biggest hurdle is getting from Chatham Point to Port Neville—a distance of 28 miles. Chatham Point marks the east entrance to Johnstone Strait and upon rounding this point you will soon find out what the strait is dishing out that day. The area around Chatham Point—which overlooks the junction of Johnstone Strait, Discovery Passage and Nodales Channel—can be deceptively calm, while a mile or two west a strong westerly could be blowing.

When the wind is calm and the sea rippled, the sight of Chatham Point light station makes a pleasing picture of red roofed white buildings backed by the Halifax Range of mountains. But if the prevailing west wind is blowing against an ebb, you’ll be focusing instead on the sea conditions in Johnstone Strait, where a very nasty chop will be awaiting off the Walkem Islands.

Tidal currents can intensify in this area and if conditions in the strait are worse than anticipated, we usually make for Mayne Passage and take the back route to Forward Harbour. There are two ways to approach this passage from Johnstone Strait. You can take it on the chin and stay in the middle of the strait, avoiding the worst of the current near the beacon south of Walkem Islands, and once abeam of Edith Point make the turn toward Mayne Passage.

The other option, not for the faint-hearted during strong winds and large tides, is to take cover from the wind in the lee of the Walkem Islands. Pass north of the largest island (marked ’98’ on chart 3543) and thread your way past the smaller islands to Edith Point, giving Ivanhoe Rock a wide berth. Upon entering Mayne Passage, westerly winds calm down east of Mayne Point and the seas lessen considerably. The flood sets north in this channel and can reach five knots.

If conditions are favourable in Johnstone Strait, we always press on. Once you’re past Edith Point, the currents aren’t too noticeable until the vicinity of Vansittart Point and there are numerous bights and bays on both sides of the strait offering temporary anchorage to wait for slack at Current Passage. One is Knox Bay on West Thurlow Island; another is the bight opposite Vansittart Point at the foot of the Prince of Wales Range. We once anchored here in 30 feet off a gravel beach, then hiked up the hillside for a picnic lunch overlooking the strait. Afterwards we realized this was where Captain Vancouver’s two ships had anchored in July 1792 after “making little progress against a fresh westerly gale.”

It took Captain Vancouver four days to transit the entire length of Johnstone Strait. His two ships—HMS Discovery and HMS Chatham—rounded Chatham Point “with the assistance of a fresh northwest wind and the stream of ebb” and began tacking their way along the strait, taking soundings near shore. When the current turned against them, they anchored in various bights to await a change in the tide. Upon reaching the western entrance to Johnstone Strait, he noted they had “beat to windward every foot of the channel.”

Fortunately, we had no headwind to contend with when we raised anchor later that afternoon. Timing your arrival at Current Passage can be a challenge on days when a strong wind is affecting surface current and delaying the predicted time of slack water. If strong westerlies are forecast, you should try to get through the passages as early in the day as possible.

As you approach Current and Race passages, the current gets stronger and turbulence will be encountered west of Tyee Point. Expect patches of whirlpools and upwelling between Ripple Shoal and Speaker Rock, and heavy tide-rips if wind is against tide. Sector lights on both Hardwicke and Helmcken islands mark the preferred route when westbound, passing east and then north of Ripple Shoal.

Helmcken Island forms a natural obstacle for commercial traffic separation: westbound vessels use Current Passage; eastbound vessels use Race Passage. Although current speeds in the two channels rarely exceed six knots, conditions can be turbulent. In deteriorating conditions, anchorage can be gained in one of the two bays on the north side of Helmcken Island, with Billygoat Bay being the most protected. When exiting Current Passage at the west end of Helmcken Island, be sure to give Earl Ledge a wide berth. There is a pronounced set onto this ledge during an ebb, so favour the south side of the channel.

West of Helmcken Island is where mariners often encounter Johnstone Strait’s worst sea conditions if a strong westerly is blowing. We once got caught in a wind-against-tide situation off Hardwicke Point. The seas had grown steadily steeper as we proceeded through Current Passage and our Spencer 35 was making little headway with the mainsail raised and engine running, so we raised the jib and soon found ourselves beating into four-foot seas. Anxious to get out of these conditions, we tacked toward a bight just west of Blenkinsop Bay, furled the jib in the lee of Jesse Island and anchored under sail in about 90 feet of water. After catching our breath, we fired up the engine and motored the short distance to Port Neville, hugging the shoreline to stay out of the whitecaps marching down the strait.

The Back Route

The back route along the mainland shore is not only a prudent option for avoiding contrary conditions in Johnstone Strait, the scenery is sublime. Fjord-like channels intersect with inlets and other channels, and milky emerald water mirrors forested mountainsides rising steeply from the water’s edge.

When northbound in Johnstone Strait, the turn-off into Mayne Passage connects with the back route. It also leads right past the Blind Channel Resort on West Thurlow Island. Owned and operated by the Richter family since 1969, this full-service marina offers shelter from winds in Johnstone Strait but beware of current, which can make docking tricky. Once you’re tied up, there is much to enjoy on shore, including a well-stocked general store, licensed restaurant and hiking trails.

At the top of Mayne Passage, where it intersects with Cordero Channel along the back route, you will find a scenic anchorage ringed by the Cordero Islands. The anchorage overlooks Greene Point Rapids and does receive some current but the holding ground is good in a bottom of mud and sand. One spot to avoid when anchoring is in front of the gap between the islands marked “81” and “59” on chart 3312. When the tide turns to ebb, there’s a strong set into the gap as current rushes into the rapids.

Timing slack at Greene Point Rapids is important, for its maximum current can reach seven knots. The current stream is fairly straight and wide, and depths are well marked on the chart, the only danger being the reef extending east from Griffiths Islet. Once you’re through Greene Point Rapids, an ebb current will help your boat speed along Cordero Channel and into Chancellor Channel. However, if a westerly is funneling down Johnstone Strait, you’ll be bucking headwinds in Chancellor Channel. In calm conditions, the vistas are magnificent, such as the one looking north up Loughborough Inlet where its numerous steep points disappear into the mauve haze.

Chancellor Channel leads to Wellbore Channel, which is the preferred route when wind against current is causing heavy tide-rips in Current Passage. These back channels were explored in long boats by Lieutenant James Johnstone in the summer of 1792. He realized an opening to the ocean lay ahead after he and his men were swamped while camped on shore one night in Loughborough Inlet—soggy proof that the flood tide was no longer flowing from the south, but from the north. This revelation diverted Johnstone’s attention from tracing the continental shore to locating a seaward passage.

He followed Sunderland Channel into the strait that would bear his name and rowed all the way to Pine Island for an unobstructed view of the open waters of Queen Charlotte Sound. Johnstone and his men were exhausted and hungry by the time they returned to the ships waiting at anchor in Teakerne Arm, but they had found a navigable channel to the ocean.

Modern mariners can simply check the tide and current tables to figure out what’s going on in this area’s labyrinth of channels. Wellbore Channel is deep and free of obstructions, and although there can be impressive whirlpools in the narrowest part of the channel at Whirlpool Rapids, turbulence is not excessive at most stages of the tide. The shores of this pass can be thick with bull kelp, so if you’re working a back eddy, take care with your prop.

For northbound boaters there are few decent anchorages beyond the Cordero Islands until you get past Whirlpool Rapids and set the hook in Forward Harbour. This scenic and spacious harbour affords sheltered anchorage off a fine pebble beach in Douglas Bay and is especially peaceful when a westerly is howling just a few hundred metres away in Sunderland Channel. There is current throughout the anchorage, so it makes sense to give other vessels lots of room.

On a recent visit we anchored in the middle of the bay, well away from the three or four other boats at anchor. We then launched the dinghy and headed ashore to hike the forest trail to Bessborough Bay on the other side of Thynne Peninsula. A woman off one of the other boats was walking her Westie on the beach and warned us that someone had spotted bear scat on the trail. Black bears are often sighted in the area, so make noise.

We had planned to spend a full day in Forward Harbour but the next morning, after listening to the marine weather forecast for wind conditions in Johnstone Strait, we decided to make the run to Port Neville. As we motored into a chilly headwind along Sunderland Channel, an eastbound powerboat was enjoying a leisurely summer cruise with the wind behind it and the sun beating down.

Whitecaps greeted us in Johnstone Strait, but we powered through them to Port Neville. When the sight of the public dock comes into view, we know the most challenging leg of Johnstone Strait is behind us.

William Kelly and Anne Vipond are the authors of Best Anchorages of the Inside Passage, a bestselling guidebook to this area.