The sheer mountainsides along Johnstone Strait give this body of water its attraction and, at times, its terror. Like a wind tunnel, westerlies can blow for dozens of miles along this strait before accelerating at its narrowing near Kelsey Bay.

So for westbound boaters, the public wharf at Port Neville, eight miles past Kelsey Bay, is a welcome sight. It opens to a sheltered inlet and an escape from howling winds. In fair weather or foul, we always look forward to this storied harbour heaving into view.

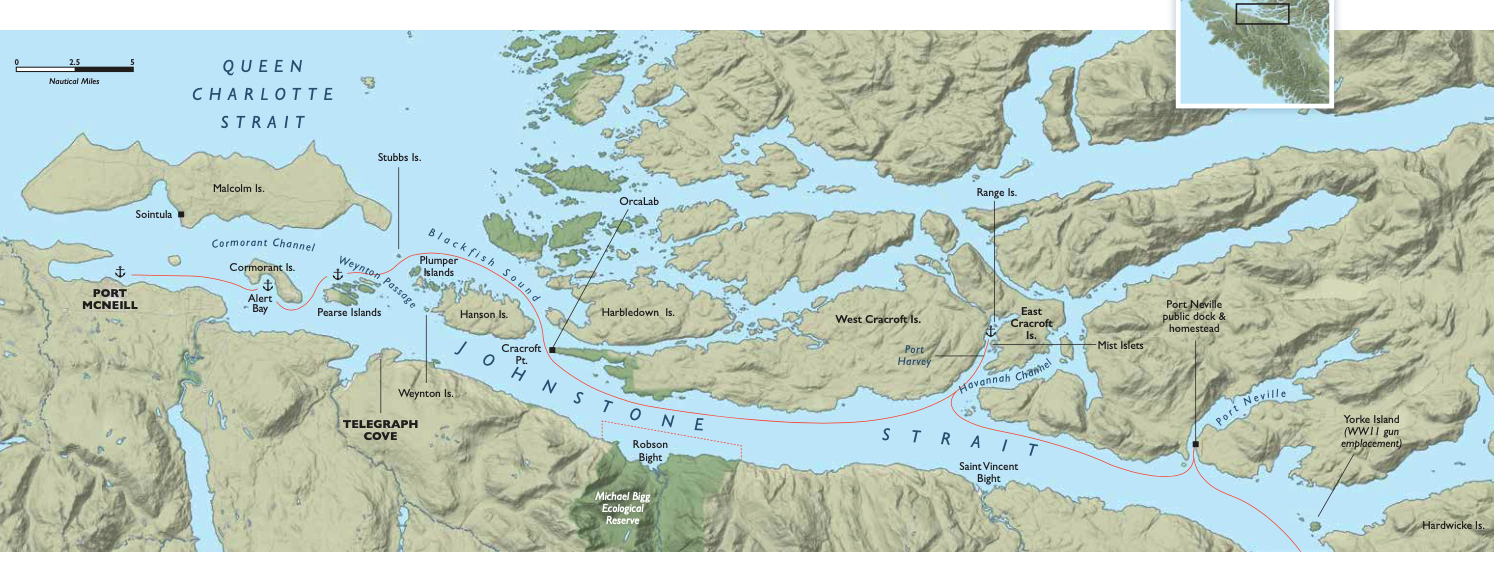

Port Neville marks the end of the major pilotage challenges for northbound boaters—namely the series of passes that start at Seymour Narrows or Yuculta Rapids and end at Race Passage or Whirlpool Rapids. The beautiful cruising grounds north of Port Neville, from Broughton Archipelago to Glacier Bay in Alaska, now lie ahead.

We have arrived here many times looking to tie up at the public dock, and in the process have met friendly boaters making their way up or down the coast. If the float is crowded, we anchor along the inlet’s opposite shore. Although kelp and current can be a hindrance, the holding ground is good once the hook has been firmly set. Getting used to the constant flow of current is part of cruising in these waters and in Port Neville up to three knots of current flows in and out of the inlet. This is a place to practise safe distancing—from other anchored boats.

The anchorage’s view out to the strait is one of tugs, fishing boats and other commercial vessels passing below Newcastle Ridge on Vancouver Island. One time we watched a sea lion catch a salmon off our stern and struggle to hold onto its catch as the fish thrashed about on the surface of the water. Then, our son John, who was 14 at the time, volunteered to row our terrier ashore. Excited as always to go for a dinghy ride, Amy suddenly lost interest once they reached shore and had barely hopped out of the dinghy before she hopped back in. There she sat, staring at John, who could now hear twigs snapping in the forest. He had just pushed the dinghy back into the water when, in his words, “a black bear jumped out of the woods!” John was pretty pumped when he got back to the boat.

On our most recent visit to Port Neville a westerly was blowing and there was room at the dock, so we tied up behind a sailboat—the only other boat there. The two young fellows on board left at dinnertime, for an “evening sail” one of them said, even though it was blowing 30 knots in the strait, and we had the place to ourselves. Gusts blasted through the inlet every few minutes but with a half dozen docking lines and lots of fenders we were secure. Current flowed by the docks keenly.

The next morning, we awoke to blue skies and northwesterly winds, with Chatham Point reporting 25 knots and gusting. In summer, when an afternoon sea breeze develops in Queen Charlotte Strait, the wind will funnel down Johnstone Strait, moving like a wave, and can reach 30 to 35 knots by evening at Chatham Point. Northbound boaters pay close attention to the forecast in Johnstone Strait. When there’s a lull in the predominant westerly winds, everyone is on the move and most boats are under way early in the morning. But when the strait is offering no respite, people tend to stay put, which is what we did.

At midday a northbound sailboat pulled into the inlet and anchored, but no one joined us at our “private” pier. It was just us and the purple martins flying in and out of their wooden houses perched atop the dock pilings. These large swallows naturally nest in woodpecker cavities in old wooden pilings but became homeless when these were gradually replaced with creosote-treated pilings. In 1985, volunteers with the BC Purple Martin Stewardship & Recovery Program came to their rescue, eventually installing nest boxes on marine pilings throughout the Strait of Georgia and Johnstone Strait.

During our day of solitude at Port Neville we enjoyed watching these acrobatic birds catch flying insects in the blustery winds. We also enjoyed several walks ashore, climbing up the steep ramp and along the long pier to the historic homestead at its head. A cedar gazebo containing a welcome plaque greets visitors with information about the pioneering Hansen family. Nearby, the ghost of a garden fronts the sea.

Several hand loggers were living in and around the inlet when 32-year-old Hans Hansen arrived in his small sloop in 1891. Promptly deciding this was where he would stay, the industrious Norwegian acquired 120 acres, planted an orchard and opened a post office. The two-storey home he built for his wife and brood of children also served as a store and, with construction of a government wharf, Port Neville became a regular port of call for the Union Steamships.

Hans passed away in 1939 but his son Olaf remained at Port Neville, settling with his bride Lilly into the log house he had built and where they raised four children. The store closed in 1960 but the post office remained open until 2010, when Olaf and Lilly’s youngest daughter moved away. Visitors are asked to respect the private property here and clean up after their pets; the long pebble beach stretching along the foreshore is a good place to take a cruising dog for a walk or let the children roam.

After a full-day stay at Port Neville, waiting for the wind to abate in Johnstone Strait, we awoke the next morning to overcast skies and calm conditions. Pulling away from the float at 07:00 hours, we joined the other boats heading west in Johnstone Strait. Recreational boaters often turn off at Havannah Channel and make their way to the Broughtons, but if the weather is fair, we usually proceed along Johnstone Strait. This is the direct route to Blackfish Sound and the harbours at Alert Bay and Port McNeill. It’s also an opportunity to do some whale watching.

Killer whales are regularly sighted in Johnstone Strait in the vicinity of Robson Bight, which is an ecological reserve established to protect the orcas that come here to rub against smooth pebbles in the bight’s rocky shallows. Renamed the Robson Bight /Michael Bigg Ecological Reserve in 1991 to honour the late Dr. Bigg’s pioneering research on killer whales, the bight is off limits to the public but, as noted in the Sailing Directions, killer whales are readily observed from the water anywhere in northern Johnstone Strait. They feed on salmon in the swift-flowing waters and often travel between Johnstone Strait and Blackfish Sound via Blackney Passage. A small research station called OrcaLab is located on Hanson Island overlooking Blackney Passage and volunteers monitor the whales’ movements with a network of hydrophones and a small video station at Cracroft Point.

Blackney Passsage leads from Johnstone Strait to the islands bordering Blackfish Sound and is used not only by orcas but commercial and recreational traffic. It’s a straightforward pass—wide and without major obstructions—but the currents are strong. Beware of heavy races off Cracroft Point on both the flood and ebb.

Tidal streams are also strong in Weynton Passage, on the west side of Hanson Island. Bill Mackay, a pioneer of the local whale-watching industry who runs Mackay Whale Watching out of Port McNeill, has seen killer whales work against a large flood (which sets southeast in Weynton Passage) by swimming close to Weynton Island and threading through the Plumper Islands. These islands are used by sea lions for hauling out, and the nutrient-rich waters in this area attract humpback whales.

Weynton Passage runs through the middle of Cormorant Channel Marine Park, which encompasses most of the Plumper Islands and Pearse Islands as well as Stubbs Island. Currents are ever-present among these islands and overnight anchoring options are limited to the Pearse Islands, where we have anchored about midway along the narrows running past the north side of the largest island. The anchorage is fairly sheltered from wind and swell but bull kelp carried along with current may catch on your rode during the night and you’ll get to listen to the sound of kelp bulbs thumping against the hull. Current may also start spinning your prop; to avoid it fouling on kelp, leave the engine in gear. Apart from these drawbacks, this anchorage is a good base for exploring these beautiful islands by dinghy.

The Pearse Islands lie at the east end of Broughton Strait, which is a continuation of Johnstone Strait and leads to the coastal town of Port McNeill on Vancouver Island and the village of Alert Bay on Cormorant Island. They each have excellent small-boat harbours and we enjoy visiting both communities. Port McNeill is a good place to buy groceries and boat supplies, while Alert Bay offers the opportunity to experience local Indigenous culture at the waterfront U’mista Cultural Centre with its famous potlatch collection. However, there could be restrictions on travel to Alert Bay this summer due to concerns about COVID-19, so be sure to check ahead before planning a visit.

Eastbound in Johnstone Strait

Our return trip to southern waters often begins after a day of provisioning and dinner ashore in Port McNeill. An early-morning departure is sometimes delayed due to fog, which becomes more frequent in August and September. However, the fog usually burns off by mid-morning and we can head back home along Johnstone Strait.

Our first overnight stop is often Port Harvey, about 20 miles from the western entrance to Johnstone Strait. This inlet lies between East and West Cracroft Islands and offers good anchorage, although its western shoreline has become busy with industrial development. The most sheltered spot is at the head, north of Range Island, but in settled conditions we like to anchor just north of the Mist Islets. The popular marina resort at the head of the inlet was sold in the spring of 2020.

Upon departing Port Harvey, we try to be east of Kelsey Bay before noon so we can clear the rapids before the wind picks up. We are wary of entering Race Passage if a strong westerly is blowing against an ebb current. In such conditions we usually exit Johnstone Strait at Sunderland Channel and take the back route [See PY July 2020]. Yorke Island lies at this junction and was the site of a Second World War military outpost designed to detect and destroy enemy ships approaching Vancouver from the north.

Twice we have stopped at Yorke Island to hike to the old ammunition bunker and gun emplacement situated on a cliff overlooking Johnstone Strait at the island’s western edge. Morning is generally the best time to pull into the kelp-strewn bight at the island’s southeast end, before the prevailing northwesterly in Johnstone Strait has time to intensify and make departure a difficult exercise.

If we’re proceeding eastbound in Johnstone Strait and approaching Race Passage, we normally favour the Hardwicke Island side of the channel until we are about a mile from Earl Ledge, then cross over into Race Passage, staying in the middle of the pass until east of Helmcken Island, after which we favour the Vancouver Island side until well past Camp Point. If battling an ebb, there is little relief until well beyond Vansittart Point.

At this point, we plan our next move based on the weather forecast. If a northwesterly is forecast, we know from experience to choose that night’s anchorage carefully because the wind will intensify in the vicinity of Chatham Point and funnel down Discovery Passage. But if the conditions are calm, we like to visit beautiful Handfield Bay or round Chatham Point and proceed southward down Discovery Passage to stop at places along the west side of Quadra Island.

As the east entrance to Johnstone Strait fades into the distance, we bid farewell to this formidable strait—until our next trip north.

William Kelly and Anne Vipond are the authors of Best Anchorages of the Inside Passage, a bestselling guidebook to the southern and central coast waters of BC.