You see them everywhere—on the hard, in marinas and, more importantly, in all the bays and coves of our popular cruising grounds—the ubiquitous Taiwan trawler. Are they, or are they not worth owning?

They came out of Taiwan in the 1970s and 1980s by the score, flooding a market that was looking for budget-priced cruising boats that were fun to own and economical to operate. Despite many of them being popped from the same mold, they were sold under a bewildering number of names—Albin, CHB, Cheer Men, C & L, DeFever, Hershine, La Paz, Marine Trader, North Sea, Puget Trawler and Universal, just to name a few.

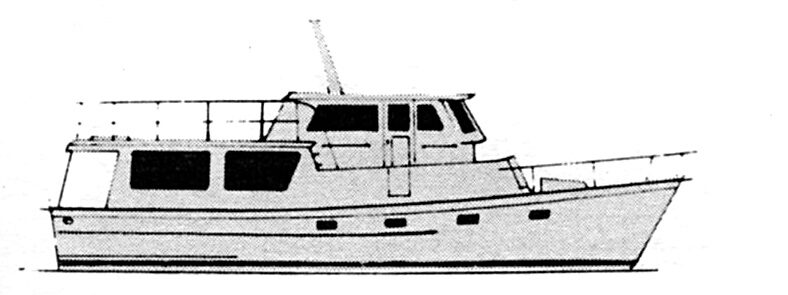

TRAWLER STYLER

The hulls were constructed using a new material called fibreglass, and many were heavily over-built. But quality control was a problem and as a result some North American yards dismissed them out of hand, calling them “Taiwan tupperware” or “eastern junk.” Others recognized them for what they were—a great way to get families into boating at a modest price.

The truth lies somewhere in the middle, and the proof of their longevity is that, 40 years on, many still cruise the Pacific Northwest every season, owned by people who would have no other vessel. Where a new 36-foot trawler will set you back $500,000 or more today, many of those classics of the last century can be had for $50,000 to $100,000. And they’ve long stopped depreciating $15,000 per year.

While some of the 1970s era trawlers had problems with poor construction, after about 1981 the industry made significant changes in quality control, and there were fewer surprises. Many of the hulls were built in a central boatyard and then farmed out to family businesses for finishing. As a result, construction and detail varied widely. One boat might have intricately carved dragons on every interior door but poorly fitted wall panels; another might have beautifully finished bathrooms but leaky windows. Yet another would have strange electrical wiring but beautiful instrument panels.

Discovering poor workmanship later might involve stripping the teak decks to discover that half the screws were missing (a screw not used, was a spare screw for the next boat). Another discovery might be that the original fibreglass deck hadn’t been swept before the deck was laid. Bumps in the decking? No problem, just plane the teak planking flat, meaning thin and thick sections later.

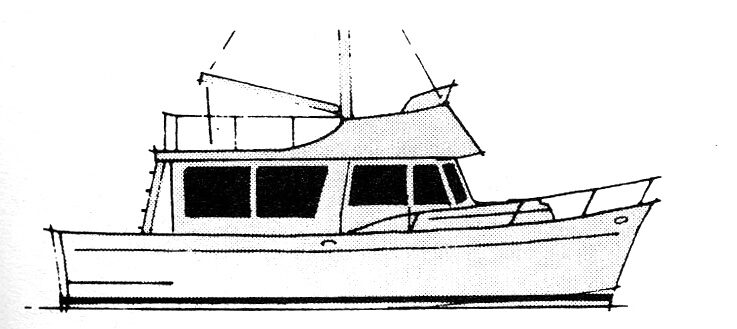

It’s not surprising that some boaters wouldn’t set foot on one. But among the lemons there are peaches to be found. Speaking from personal experience, I searched for a specific style (a europa, rather than a sedan, tri-cabin or sundeck) for nearly two years, before finally buying one all the way across the country in upstate New York, then shipping it back to the Pacific Northwest on a truck! Why? Because it was exactly what I wanted. But I looked at a lot of boats in BC, Washington and as far away as the upper Columbia River in Oregon before finding that New York boat.

Today, dollar for dollar, they are some of the best deals in the leisure craft industry, and as some approach 50 years, many are still in fair shape. Usually powered with a single 120-horsepower Ford Lehman naturally aspirated diesel, or less often with a 130-horsepower Perkins, they aren’t great performers, chugging along at hull speed (six to eight knots), but burning a thrifty one litre per mile. Neither the Ford Lehman 6D380 nor the Perkins 6.354 are produced any more, but spares are still easy to find and reasonably priced.

While many potential buyers will see the low operating costs as a powerful incentive, we should add a note of caution—as with any older equipment, it helps to be handy for the inevitable things that break. But the main components, the hull, the deck, the engine and the layout can be solid (subject to some caveats listed below). Remember, wiring, instruments and tanks can be dealt with as and when necessary. In the meanwhile, the difference between that $250,000 vessel and your $50,000 one is sitting in your bank.

In the mid-‘70s, New Jersey entrepreneur Don Miller of Marine Trading International began importing a 34-foot aft cabin model from Taiwan, designed by marine architect Ed Monk. It was an immediate success. Where else could you get a complete cruiser, with parquet floor, instruments, smothered in teak, even curtains, for $25,000? It’s estimated that Miller imported over 3,000 trawlers in the following decade.

Copycats appeared almost immediately. Labour costs were cheap across the Pacific, and there followed a wild scramble as many small boatyards got into the fabrication business, jobbing out sub-contracts to family and friends, and then merging the finished trawlers under various marketing names. Don Miller’s boats, unsurprisingly, became known as Marine Traders.

Sinclair Wen owned the Chung Hwa Boat Building Co. where they produced CHBs and LaFitte sailboats. In the late 1970s he bought a share of the Kadey-Krogen line, which was producing the popular 42-foot cruiser. Apart from interior layout changes and a small increase in length (44 feet), that design has been in production for over 40 years!

Alexander Chu, who had worked at C&L, went on to start Ocean Alexander with a 50-foot pilothouse model that could be bought for $125,000. Today, its sequel, the 60-foot pilothouse, costs over a million. The company is still in business, manufacturing luxury yachts that have made their mark around the world.

Arthur DeFever designed a line of blue water cruisers that proved popular, although others quickly copied them. So was Bill Hardin’s classic Coaster 33. Originally built by CHB, it wasn’t long before look-alikes were coming out of all sorts of yards under the names of Heritage, Golden Gate, Bluewater, Far East and more. And the quality varied.

The habit of copying the industry leaders almost became an epidemic. A story from Don Miller illustrates the situation in the late 1970s. While at the boatyard in Taiwan, he ordered 23 changes to the design. Two weeks later back home, he saw that other importers were advertising the same 23 changes! It was a competitive market, and as Miller freely admitted, Taiwan trawlers weren’t the best boats, but they were very good value. They remain that today, in part because the exterior appearance of those early boats hasn’t changed much (unlike cars or houses). A 1978 36-foot Albin looks surprisingly similar to a 2001 Island Gypsy, or a brand new Grand Banks Classic. The tri-cabin design is timeless.

But times move on; where once they were mostly built in Taiwan, today many manufacturers have moved to China where the cost of labour is lower. As in Taiwan, the first few years’ models have had QC issues.

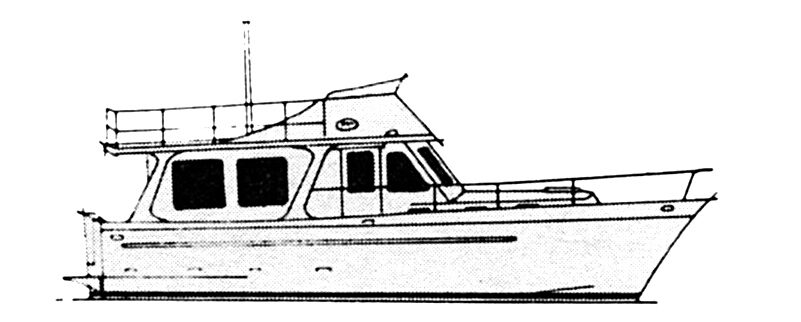

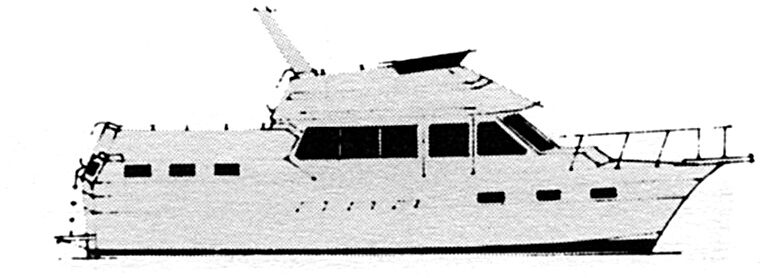

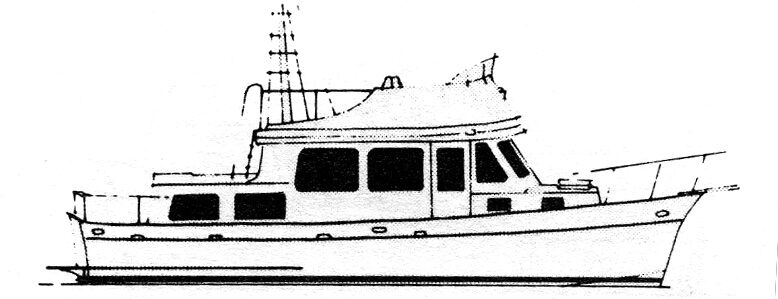

So, you’re thinking about a Taiwan trawler. First, decide which of the layouts will suit you best. You have kids? A sundeck or tri-cabin has the benefit of a bow cabin with bunks and head, separated from the aft master cabin and second head. It’s good to keep the noise apart. A tri-cabin, by the way, is sometimes called a double-cabin, as it has fore and aft sleeping cabins. The tri-cabin description just includes the central saloon in the cabin count.

Are you likely to be just a couple on board? The europa or sedan with a larger master cabin with centreline bed and small second cabin, with just a single head might be a better use of space. Plan to fish off the aft deck? A sedan or tri-cabin gives the best cockpit space.

Suffer from claustrophobia? The full width of the sundeck master cabin is a good option. Are you a light sleeper? Don’t buy a sedan or europa with the main cabin in the bow, where you’ll hear the lapping of waves all night on the hook. Bad knees? Avoid a europa with its steep companionway, where a tri-cabin lets you reach the upper helm in a series of short, easy stairs. Planning on spending time cruising in the shoulder seasons? Get a europa with its broad upper deck that screens the lower windows, and lets you leave the doors open, even when it’s raining.

Now that you have an idea of what you’re looking for, develop a relationship with a broker and a marine surveyor, both of whom specialize in trawlers. They are just like medical doctors—there are specialists in every field, and it helps to get advice from someone knowledgeable about trawlers, rather than luxury yachts or fast tugs or sailboats.

Before you call in the hired help, have a preliminary checklist for when you’ve found one you like. Your time is free. Taiwan trawlers can have leaky windows. Check for discolouration below the sills. They have a reputation for leaky decks. Water gets under the teak deck and runs to the lowest point, which is about 2/3 of the way toward the stern, at the deck’s lowest point, where it pools under the boards and finds a screw hole to penetrate the sub-deck. Does the deck feel soft there? Can you get into the engine room and see the underside of the deck? Is there visible water damage? That low point is often where the water tank fill pipe is. Does it look corroded?

Small deck areas can be repaired quite economically. Check the internet, especially trawler forums. There are several ways of curing a boat with small sections of soft deck, without ripping up everything and starting again.

Are there cracks where the superstructure abuts the deck? What this can suggest is not a soft superstructure, but a soft hull. It might mean the hull stiffeners aren’t doing their job. There are four beams (stringers) that run fore and aft along the inside of the hull. The middle pair usually carries the engine. Across those stringers, ribs stiffen the hull sideways. Over the long life of the boat, a prior owner may have drilled holes to run pipes or electrical cables. If bilge water has penetrated the stringers, the wood rots and the hull starts to flex in the swell. That in turn means anything attached to the hull (the engine alignment, prop shaft, upper cabin, deck penetrations), all flex too. Make sure that the surveyor checks the moisture content of the stringers.

In the superstructure, water penetration can soften the frame and be expensive to repair (usually from the inside). This is less of a problem on europas, which have a wide upper deck that sheds the rain. Like the hulls, the amount of structural material in the superstructure can vary from vessel to vessel, some being massively thick, others paper-thin. One check is to remove the shore power fitting to see the wall’s cross-section.

Another thing to consider is poor resin penetration of the fibreglass during construction. This usually manifests itself as spider web cracks and chips, exposing dry chopped mat beneath. Depending on where they are, they can be cosmetic, or can be the inlet for water that over time can destroy walls and decks. Hulls, on the other hand, were mostly over-resin coated, with the result that blistering and osmosis is less common. But certain brands had a bad reputation for poor hull construction. Make sure the surveyor does a thorough hammer check.

Tanks are another issue. Some old fuel tanks were welded steel. A flexing hull causes tanks to buckle and leak, usually at the welded corners. Tank removal is a slow process, but needn’t be a deal breaker. If you’re reasonably handy, grinding up an old tank into pieces to remove through the engine room hatch, and installing multiple small tanks (to fit through the same hole) is not as difficult as it initially appears.

When viewing a prospective boat, the engine room can tell its own story. Learn to read it. Rusty parts and junk lying about imply the owner either doesn’t care, or doesn’t go down there often. Polished pipes and oiled surfaces suggest regular servicing. Have an oil analysis done—it can tell you a lot about the bearings. Do the fuel and oil filters look new? Are the batteries clean on top? Does the wiring look tidy or tangled?

According to the late Bob Smith (engine guru), Ford Lehman engines, if looked after, can go for 20,000 hours before a rebuild on the block. Replacing peripherals like heat exchangers, pumps, hoses and exhaust manifolds are just part of the business of buying an older boat. Set aside an additional 15 percent of the purchase price for upcoming issues, and try to do as many of the repairs yourself. That way you’ll learn about your boat, and save yourself money.

Bright work is another concern for some buyers. All that magnificent outside teak needs to be stripped and re-varnished to retain the look. Modern varnish does last longer, or you can just let your rails go au natural. Weathered exterior teak shouldn’t be a reason to turn down a boat, but you’ll notice that since the 1990s, teak hand and cap rails have gone out of style because of the maintenance issue. That still leaves exterior window frames, handrails and trim. I’ve taken to painting them—a good marine paint lasts three to five years, whereas varnish lasts one to two.

The best advice when buying a Taiwan trawler is to educate yourself. Look at many models. Ask questions. Concentrate on the later models (1982 to 1990) as materials and construction methods did improve. Find a good marine surveyor for that day when you discover the one that ticks most of your boxes. And remember, no boat 30 to 45 years old will tick ALL the boxes.

Be realistic. Understand that most Taiwan-built trawlers aren’t blue water boats (there are a few exceptions). However, for sheltered cruising such as in the Salish Sea, they are perfect. And know that when you find that diamond in the coal heap, you’ll have a sturdy, seaworthy partner to share adventures with for as long as you’re both able to put to sea! Happy cruising.