In this age of electronic depth sounders, you may think you need a leadline as much as you need a peg leg… but think again. There are several things that a leadline will do for you that an echo sounder won’t and since, as sensible mariners, we follow the cautionary dictates of the Collision Regulations, to “take all available means” when navigating, let’s examine what this worthy instrument can accomplish, how to use it and how to make one.

What Is It?

On one end of a line, we have a piece of cast lead, weighing 1.5 to four kilograms (approximately three to eight pounds) with a hollow in the end of it. You can usually buy the lead from a traditional ship chandlery and add the line and marks yourself. The hollow is for ‘arming’ the lead with tallow (rendered fat) or, if you can’t lay your hands on tallow, fill the cavity with grease or lard (Crisco). What is this sticky mess for? To tell you what the sea bottom is like—sand, mud, fine shells—or if nothing sticks it is probably bare rock (don’t anchor!). And, as we all know, different anchors may be needed for different bottoms, so this is very useful information provided by our humble leadline. In a pinch, you can use any reasonably heavy weight (like a large shackle) but you may not have the advantage of “picking up the bottom.”

How to Use It?

When you are ready to heave the lead, take a position just forward of the ship’s maximum beam, make yourself secure and comfortable (a sailboat’s shrouds work well) and ensure the “bitter end” of your leadline is made fast (as you don’t want to toss the whole thing over the side by accident). Now it is important that if your vessel is moving forward it is doing so very slowly or you won’t be able to get an accurate reading. Cast the lead forward and let the line run out. The line will go slack when the lead hits the bottom; take up the slack so that the line is straight up and down when you come abeam of it. Look down and observe the mark closest to the level of the water (see Marking the Leadline below). This is not as simple as it sounds but with a little practice you will soon master the art of heaving the lead.

The Leadline’s Many Uses

- Piloting

When cruising, we often face entering a tricky harbour, an unexplored creek or some backwater that offers the additional challenge of a sunken snag or an abandoned wreck. This is when the leadline comes into its own: it is compact, portable and lightweight. Put it into the dinghy and take a few soundings before you venture in with the larger boat. With a particularly difficult entrance, mark the safe course with floats made up of fenders or plastic bottles tied to weights.

- Crossing a Shifting Sand Bar

No chart, however accurate or up-to-date, can provide the latest information on a sand bar with a navigable channel that shifts with the vagaries of wind and currents. Once again, sound the deepest passage with the dinghy piloting ahead and the lead being heaved regularly. Remember, it is always best to attempt these sorts of maneouvres on a rising tide… just in case!

- Running Aground

If you do run aground, the first thing to do is determine in which direction the deepest water lies. Get out the leadline and sound all around the ship. This will give you a good indication, which can be confirmed when you venture farther afield in the dinghy, taking more soundings with your trusty leadline. The kedge anchor can now be taken out and dropped in deeper water.

- Checking the Echosounder

Most yachts with electronic depth sounders will have a transducer attached to the hull somewhere between the keel and the waterline. This means, of course, that without calibration, your depth sounder is not correctly reflecting the depth of water; fortunately, there is more water than indicated on the screen. Normally, the sounder is calibrated, or we know by experience how much to add if it is not. It is not a bad idea, however, to check your electronic instrument from time to time when you are at anchor or tied to a dock. Once again, the leadline comes into play so you can determine whether your calibrations (or calculations) are still accurate.

Marking the Leadline

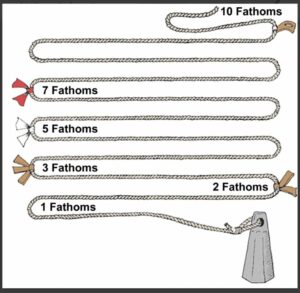

Most of us know that the famous American author and humorist, Mark Twain, was actually Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Before achieving fame as a writer, he was a Mississippi steamboat pilot and chose his pen name from the “marks” of a leadline. You can easily make up your own hand lead (leadline used in shallow waters) with three-strand line attached to the lead and marked as follows, where one fathom is six feet: