Captain Leonard Locke, 66, like all captains, was a stickler for punctuality, but he was running late. Six of his crew had the Spanish flu requiring Locke to find last minute replacements. He waited impatiently for late passengers to board the Canadian Pacific steamer Princess Sophia, moored in Skagway Alaska. They were leaving the north that Wednesday evening to escape the cruel winter; some were moving south for good. Finally, at 22:10 hours, three hours behind schedule, the docking lines were thrown off and the 245-foot, single-screw ship began the first leg of its journey down the 90-mile Lynn Canal—Alaska’s deepest fjord—toward Alaska’s capital, Juneau.

Built in 1912, Sophia was one of Canadian Pacific’s (CP) newer coastal cruisers, not as luxurious as its Empress Class, but comfortable with a good reputation and reasonable fares. With the October 23, 1918, departure, the steamship began its last voyage of the year—ice prevented her from transiting these northern climes during the long dark winter. The 117 Canadians, 121 Americans, one Scot and 39 of unknown origin who boarded included prospectors, business people, miners and their families. The crew made up the rest of the 343 people aboard (the final number of people on board is disputed; some say it may have been as high as 354). The cargo included five tons of freight, 24 horses, five dogs and $132,000 in gold ingots.

After Sophia’s departure, the weather deteriorated quickly; gale-force winds and a whiteout snowstorm caused the ship to wander 1.25 miles off course. At 02:10, she crashed hard into the unmarked Vanderbilt Reef. The Reef is the pinnacle of an underwater mountain that rises 1,000 feet from the ocean floor.

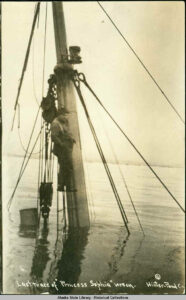

Despite a fleet of vessels that assembled the next day to rescue passengers, Locke judged lowering lifeboats too risky in the atrocious weather and told the rescuers to seek shelter. He thought the ship would remain perched on the reef until conditions improved. But when the rescuers returned the next morning on October 26, only a piece of Sophia’s foremast was visible. All aboard had perished.

Although this shipwreck and loss of life were the worst recorded on the northwest Pacific coast (it’s sometimes called the unknown Titanic of the west coast), news of Sophia’s sinking quickly moved to the back pages. There was jubilation when World War I ended two-and-a-half weeks later, and the rapid spread of the 1918-1919 Spanish flu that killed many millions worldwide overwhelmed news of the shipwreck. But Sophia is not entirely forgotten.

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the tragedy and also highlight how her foundering contains lessons for seafarers—and governments—today, the Maritime Museum of British Columbia (MMBC), in cooperation with the Vancouver Maritime Museum and the Alaska State Museum, is unveiling an exhibit, the “Sinking of the Princess Sophia,” on January 12, 2018. The exhibit will later travel to Juneau and the Yukon.

Why did the Princess Sophia sink? She was a seaworthy ship. Built in Scotland, she’d weathered the arduous 14,500-mile trip to Vancouver around Cape Horn. Captain Locke and his crew were experienced seafarers. Was Locke with his officers when Sophia hit the reef? We’ll never know. Our knowledge of the events aboard is incomplete—the logbook was never recovered.

The northern gale whistled down the Lynn Canal, battering the ship, while the heavy snowstorm reduced visibility. To establish Sophia’s location, crew frequently blew the ship’s whistle and then counted the seconds it took to hear the echo bounce off the mountains. Undoubtedly, the shrieking gale and dense snow distorted the response. The black night, waves and the ship’s pitching obscured the buoy near the Vanderbilt Reef, located 54 miles south of Skagway. When she smashed bow first into the reef at 11 or more knots, the crash threw people from their berths and flung the crew on the bridge into the bulkheads. Sophia radioed for help. But the steel double hull remained intact and Locke hoped the high tide would float the ship off its rocky perch. Instead, the next 16.4-foot high tide lifted the ship but settled her more firmly into the reef’s centre groove. The storm persisted and the huge waves breaking against the reef made it unsafe to launch the liferafts. Rescue vessels, including the Cedar, the King and Winge, the Estebeth and the Peterson, stood by helplessly while seriously risking their own safety. Locke sent them off for the night.

The 15-foot flood tide was its high point around 16:45 and caused the ship’s bottom plates to tear on the jagged rocks. The boilers blew up causing tremendous damage; the fuel tanks ruptured. One can only imagine the fearful screeching of torn metal, the deafening explosions and everyone’s horrifying knowledge that death was imminent. With seawater rushing into the hull, Sophia toppled down onto the reef’s shoals around 17:50, as determined by the passengers’ watches that stopped at that time. Some passengers drowned in the icy water; most were asphyxiated when inhaling the billowing oil into their lungs.

According to The Sinking of the Princess Sophia, by Ken Coates and Bill Morrison, the force of wind, tide and waves lifted the stern, then turned the ship 180°, pivoting its bow into the wind. In 2009, the Sea Hunters’ James Delgado supervised a dive on the wreck that appears to confirm that view. Although Sophia now rests in pieces on the side of the mountainous reef at depths ranging from 40 to 120 feet, the diver was able to observe the ripped bottom plates and the engine room’s devastation—now covered by abundant plantations of white anemones. Moreover, the wreck lies on her starboard side—a strong indication she tumbled down the reef with her bow pointing north.

The Aftermath The next morning, the returning rescuers sadly began to collect bodies that had dispersed in the area, some afloat, others washed ashore. CP offered $50 for each body recovered. Divers retrieved victims trapped inside the ship. They were transported to Juneau where volunteers had to use gasoline to wash away the dense oil coating the bodies. Ironically, Sophia was built as a coal-fuelled ship; she’d been converted to oil shortly after arriving in B.C.

An official inquiry began in Victoria on January 6, 1919. Captain Locke’s decisions were vigorously questioned. He had run the Sophia at about 11 to 12 knots in weather conditions that usually dictated a speed of no more than seven knots. And the rescue boat skippers believed there had been opportunities to unload the passengers when the storm moderated somewhat. CP vigorously defended Locke’s judgments and in the end, no blame was assigned to either the captain or the company—thereby allowing CP to collect the $250,000 insurance. The “Report to the Marine and Fisheries Ottawa,” stated the Princess Sophia was lost due to “perils of the sea.”

Small payments for funerals were made to the families of passengers and crew. The inevitable lawsuits dragged on into the 1930s but eventually petered out. And a light finally marked the Vanderbilt Reef after many earlier requests had been denied. The reason? The Lynn Canal was considered wide enough to make a beacon unnecessary.

Sophia’s Lessons Today, navigation of the Inside Passage demands care but travel is no longer treacherous. Excellent hydrographic charts, radar, sonar, GPS and Search and Rescue (SAR) services have made shipping much safer. But Sophia’s disaster should give us pause—ships have now started traversing the Northwest Passage with many of the same dangers Sophia faced. The weather, even during the North’s summer, is more unpredictable and brutal than in the Lynn Canal, with sudden storms, white-outs and impenetrable fogs.

In 2017, five adventure ships, with passengers ranging from 150 to 300 crossed the Arctic. The sixth, the 820-foot Crystal Serenity, with a total complement of passengers and crew of 1,500, traversed the Arctic from Anchorage to New York. Admittedly, she installed a new ice detection system and engaged pilots with ice navigation experience. A research vessel with icebreaking capability accompanied the cruise ship. Fortunately, the behemoth made it without accident, just as Sophia had made her previous voyages without mishap.

But suppose the Crystal Serenity had hit ice? Or found her own reef? SARs are too scarce and too distant to help. There’s no way locals could save 1,500 people, many of whom are seniors. Does this sound like scaremongering? A recent example illustrates the danger.

On November 23, 2007, the Explorer sank off Antarctica in the Antarctic’s late spring. Unlike the Crystal Serenity, she was an ice-hardened adventure ship built for high latitudes with passengers who had to show physician-attested fitness. Yet when Explorer hit old, hard ice, two or more of her lower plates split, water poured in and the ship listed quickly. The 150 passengers and crew crowded into open lifeboats and, after slopping around for five hours in icy water with threatening bergs, they were extremely fortunate to be rescued by a Norwegian cruise ship. Five hours after that rescue, gale force winds and a blizzard would have drowned them all. Explorer sank 16 hours after hitting ice.

What if one of today’s high-latitude cruise ships experienced a catastrophe like Sophia or Explorer? No other ships capable of saving the numbers aboard would be close enough to rescue them. How would those on the accompanying research vessel choose whom to save? Assuming there was time to load all passengers and crew into lifeboats, how long could they survive?

And if, like the Sophia’s, the cruise ship’s huge tanks were breached, the environmental disaster would be immense. Sophia’s oil fouled the nearby shores for years. Canada needs to assess this potential danger to life and the environment and take measures. The “perils of the sea” argument is no longer acceptable. Should large, unsuitable cruise ships be prohibited from crossing Canada’s Arctic?

It’s time to start the conversation.

[Sidebar]

The Human Side

When a ship sinks, the focus usually falls on the causes of the catastrophe. But there are more than 340 personal stories of those who lost their lives when Sophia foundered. A few left a direct legacy by writing letters, later found on their bodies.

Here’s an excerpt from John Maskell’s letter to his fiancée, Dorothy Burgess.

My dear own sweetheart, I am writing this, dear girl, while the boat is in grave danger. We struck a rock last night . . . the lifeboats were soon swung out in readiness, but owing to the storm would be madness to launch . . . the first steamer came but cannot get near owing to the storm raging and the reef we are on . . . The boat might go to pieces for the force of the waves are terrible, making awful noises on the side of the boat . . . I made my will this morning leaving everything to you, my own true love and I want you to give £100 to my dear mother, £100 to my dear dad. . . and the balance of my estate (about £300) to you . . . .

Signed J Maskell

And an excerpt from the letter Auris McQueen, 35, U.S. Army signal Corps, wrote to his mother.

Dear mama, the Princess Sophia is on a rock and when we get away is a question. It’s storming now, and we can only see a couple of hundred yards on account of the snow and spray. We passed the first real danger point at high tide at 6 am . . . We had three tugboats here in the afternoon, but the weather was too rough to transfer any passengers. The most critical time . . . was at low tide at noon when the captain and chief officer . . . were afraid she would turn turtle but the bow pounded around and slipped until she settled into a groove . . . The decks are all dry and this wreck has all the markings of a movie stage setting. All we lack is the hero and a vampire . . . .

Lovingly, Auris

Sources

The Sinking of the Princess Sophia. Ken Coates & Bill Morrison. Oxford University Press, 1990.

The Final Voyage of the Princess Sophia. Betty O’Keefe & Ian MacDonald. Heritage House, 1998.

Stranded. Aaron Saunders. Dundurn, 2015.

The Sinking of the Princess Sophia. National Filmboard of Canada, 2004.

Research by the Maritime Museum of British Columbia.

ShipwreckCentral.com/, www.youtube.com/watch?v=zm-RZb7K8eI/.