It was Bilbo Baggins of Middle Earth who commented that hobbits had no use for adventures, because they made you late for dinner. Happily, while boating is itself an adventure, you usually have the galley along for the ride, so missing meals isn’t a problem.

Getting off the boat, on the other hand, is another story, even if it’s just for a short hike somewhere. Boaters live by the tides, wind and weather, so they’re aware of the elements while at sea, but you don’t want a little land adventure to make you late for dinner. Be sure to take along a snack or two, even if you think you’ll be back early. It’s odd how often we “go for an hour,” but come back at dusk, tired and very hungry!

Wear sensible shoes. Wrap a rain jacket around your waist, and put a broad-brimmed hat on your head. And make sure there’s a candy bar in your pocket. Then get out there and enjoy the wildness of the Gulf Islands. There may not be any wifi, but there’s a better connection waiting.

Wallace Island: From Conover Cove or Princess Cove

To Panther Point (SE)

Elevation gain: 10 metres

Distance (return): 2.2 kilometres

To Chivers Point (NW)

Elevation gain: 30 metres

Distance (return): 8 kilometres

Wallace Island in Trincomali Channel was originally named Narrow Island, and for good reason. It’s almost four kilometres long, but barely 250 metres wide for much of its length. It was renamed by the Royal Navy for Capt. Wallace Houstoun of HMS Trincomalee, who first charted the area in the 1850s.

After The Second World War and until the mid-’60s the island was developed as a holiday resort. The remains of the cabins can be seen above the jetty in Conover Cove. The owner David Conover wrote Once Upon an Island describing those years, with sequels One Man’s Island and Sitting on a Salt Spring. The island became a provincial park in 1990. Be aware that a small section of the west shoreline, north of Princess Cove, is still private property. The lion’s share (180 acres) is parkland.

Anchor in Conover Cove or Princess Cove, both of which are popular in the summer months. There’s a long reef that parallels the east shoreline, so care should be taken reaching either anchorage. There’s limited swinging room in both, so a stern tie is advised, unless you’re lucky enough to get on the short jetty at Conover. On spring tides, the jetty berths are for shallow draft vessels only. There’s a dock fee per metre, per night.

Which way to walk? For such a narrow island, sea views are surprisingly few except at the northwest and southeast headlands. Panther Point to the southeast is a considerably shorter stroll, so unless you are set on a long walk, let’s go south. But not before visiting the camping enclosure on the north side of the lawns, where visiting boaters have added a plethora of vessel names in many styles—worth a visit.

A 20-minute walk to Panther Point brings you out to a fine view down Trincomali Channel (note the spelling difference from the original RN survey ship). There’s a reef that extends beyond the land and, in keeping with the tradition of naming marine hazards after the ships that hit them (thereby immortalizing their captain’s negligence), the point is named after the merchant collier Panther that ran aground and later sank there in 1874 with a full load of Nanaimo coal. Divers still explore the wreck.

Mount Maxwell, Salt Spring Island

Elevation gain: 580 metres

Distance (return): 7 kilometres

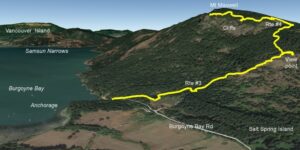

This is one of our all-time faves. Like the climb from Cape Keppel up Mount Tuam on the southern end of Salt Spring Island (see PY August 2018), this is a steep but easy hike that gets you far above the tide line. Although there are lots of trails (which might be confusing), there are also useful maps mounted on posts at key cross paths, with helpful “YOU ARE HERE” stickers, which minimize uncertainty.

If you don’t want to do it all, there are several fine viewpoints on the way up, where the panorama is almost as good as the top. If you do go for the summit, the hike rewards you with a stunning vista—looking west over Burgoyne Bay into Sansum Narrows is reminiscent of the wilderness around Desolation Sound.

Anchor at the southeast end of Burgoyne Bay, mindful of the drying flats, in five to 10 metres over good holding. There is an eclectic collection of houseboats and derelicts moored in the roads. Burgoyne Bay Road reaches the east corner of the beach. Follow it 200 metres up to a car park on the left. Just ahead, three concrete barriers close off an old road where there’s a handy map mounted on a post that shows the Mount Maxwell trails (which are all numbered). You will be following #3 for most of the way up.

After about five minutes, there’s a fork to the left. Ignore it—it leads west above the Burgoyne Bay shoreline. Instead, take the right-hand fork. After about 20 minutes there’s another fork, also un-numbered (these are the only two points of uncertainty). Take the left-hand fork this time. The right-hand one had branches laid across it when we were there, and was clearly unused.

From here on, any time there’s a fork there’s a map too and the route is well signed with #3 markers on trees. After half an hour you break out onto open ground. The first views southeast to Fulford Harbour and the Gulf Islands appear. You enter a pretty garry-oak forest as you climb further. After about an hour you’ll reach a fork (with a map post). Off to the right a hundred metres there’s a viewpoint that’s worth detouring to, or if your sea legs aren’t up to snuff, it’s a good turnaround spot.

Back on #3 trail, the oak forest yields to Douglas fir and redcedar. Higher up you pass some massive first-growth trunks. Keep an eye out for a cross trail (clearly marked on trees as #4) and when you reach the fork (and another handy map post), make a left. There are lots of #4 tags on trees.

There’s a final steep section before the track starts contouring left, gaining height more gently, and you find yourself above the cliffs. As you near the top, there are more trails and viewpoints off to the left. Follow your nose to a chainlink fence, a lawn, picnic tables, a pit toilet and jaw-dropping views. Be aware there’s a 4WD road up the back of the mountain, so you’re unlikely to be alone.

Lean over the fence, enjoy the panorama, spot your vessel far below in the bay and realize that not long ago this bluff was a favourite jumping off point for hang gliders. Those magnificent men in their flying machines would land in the fields near the Ganges-Fulford road.

There’s some interesting history here. Salt Spring Island was originally named Admiral Island in honour of Rear Admiral Robert Baynes, and Mount Maxwell was named Baynes Mountain. Burgoyne Bay was named after an Irishman, Captain Hugh Burgoyne. All three names were given by Captain Richards of HMS Plumper in 1859. Admiral Baynes commanded the Pacific Fleet from 1857 to 1860. However, locals called it Mount Maxwell after John Maxwell who farmed in the area in the late 1800s.

Burgoyne, while just a lieutenant, won the Victoria Cross during the Crimean War in 1855, at the tender age of 21. Sadly, he died at just 37 when in command of HMS Captain, which capsized off Cape Finisterre in northwest Spain during a gale in 1870. The Captain was a revolutionary masted turret ship that had been the subject of considerable controversy, and its loss was attributed to poor stability. Turret ships had swiveling guns rather than the more traditional broadside arrangement, and HMS Captain was the forerunner of the massive battleships and dreadnoughts which reached their zenith in the First World War.

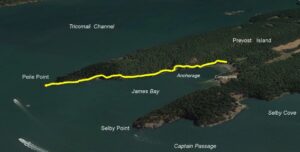

James Bay to Peile Point, Prevost Island

Elevation gain: 50 metres

Distance: 3 kilometres

The northern section of Prevost Island is part of the Gulf Island National Park Reserve and a perennial favourite anchorage. Although a bit exposed to a northwester, it’s usually pretty snug in the summer, and is bomb-proof in southeasters. Anchor in five to 10 metres with good holding.

Land at the back of the bay, or on the shell/mud beach at the campground just to the southwest, where there’s an orchard that still produces fruit in late summer. The trail starts from the back of the bay next to a large park sign, and follows the north side of the bay. However, although it parallels the shore, do not for a moment think it’s level. It goes up small hillocks, never more than 20 metres, and then descends again to near the water before going up another. Every time we hike it, it puts us in mind of G.K. Chesterton’s poem “The Rolling English Road.”

on Prevost Island makes a pleasant destination from the back of James Bay, providing views east across Trincomali Channel to Montague Harbour and Galiano Island.

Your effort is well rewarded. There are good views into James Bay from several high points, there are stonecrop and monkey flowers among the rocks and, where the land tapers to the Peile Point light, there’s grass with spreading garry oaks overhead. The views up Trincomali Channel to the north and down Captain Passage to the west are a treat, while ferries emerge and disappear into Active Pass to the east.

On an historical note, Trincomali Channel was named by Captain Richards (again) for the 1,000-ton frigate HMS Trincomalee, 24 guns, that arrived in Esquimalt in 1853. She was built in India in 1819 and named for the Indian port city of the same name.

Captain Passage has a similar origin. The channel was named after Captain John Fulford, in command of Adm. Baynes’ flagship HMS Ganges. (It should therefore be apparent where two more well known Salt Spring Island names originated.) Peile Point is named after Lt. Mountford Peile who served on HMS Satellite under Captain James Prevost.

The Royal Navy, as first cartographers of the region, showed a woeful disinterest in enquiring about or including First Nation names, many of which had likely been used for millennia. Instead, chart makers tended toward flattery for royalty, patrons and senior officers, by sprinkling their surnames around like popcorn at a matinee.

Pirates Cove Circuit, De Courcy Island

Elevation gain: 25 metres

Distance: 2 kilometres

The history of De Courcy Island is tied up with Brother XII, his whip-wielding mistress Madame Zee and a lot of buried treasure, which may explain why the cove is so popular in the summer months. Or, possibly it’s because the basin with the tricky entrance is well sheltered from most winds (except northerlies on a high tide).

There are two dinghy docks, and we always walk from one, looping back to the same one, so as not to call for assistance to recover the dinghy. A favourite option, if we have youngsters in tow, is to visit the treasure chest out on the cove’s natural breakwater, while spinning the gullible youth a tale about how seldom the chest is found open. “Usually,” we say with sincerity on our voice, “that metal chest is locked tight. But sometimes… well, you never know!” The delight on the young ones’ faces when they find the chest open, and goodies inside, is a real highlight of any visit.

Another highlight is to follow the shoreline round the east side at low or medium tides. The sandstone slabs angle gently to the sea, and the walk is easy, the logs thrown up by storms always interesting, and there’s the added pleasure for the sneezy in spring, of not wading through pollinated grass on the Pylades Trail that parallels the shore.

Follow the coastline round into Ruxton Passage and back to the neck between the main De Courcy Island and its southeast outlier. To get back to your dinghy near the cove’s entrance, climb the many stairs and take either of the trails back through the forest—the Brother XII Trail is a bit longer than the Darkwoods Trail, but both are worth walking.

Dionisio Point, Porlier Pass

Elevation gain: minimal

Distance: 2 kilometres

Porlier pass has always been one of those places we’ve avoided, and for good reason. Currents can rip through there at over seven knots, and sensible folk try to avoid such places. But times change and the acquisition of a reliable RIB with outboard power has altered our attitude a bit. Leave the mothership in the safety of the Gulf Islands, and just nip through as easy as winking, right?

Where to leave the big boat? Approaching from the west, there’s Baines Bay on the north end of Galiano Island, a tiny pocket that could hold a boat or two but no more. Unfortunately, when we visited, there was already a vessel moored there that looked like it had been there a while, with no plans to move any time soon. Baines was not an option.

Heading through the pass, there’s a deep and somewhat shadowed slot—Lighthouse Bay—which lies between the old squat white lighthouse (on Virago Point, now non-operational) and the modern white column light on Race Point. Lighthouse Bay is narrow, but there’s fair holding (sand mostly) opposite the old lighthouse warehouse and wharf. Some reports are that the bottom is foul.

Our choice was to anchor well out of the swirls and back eddies that sweep the pass, just north of Cardale Point on the southwest end of Valdes Island. From there, the dinghy took us through the boils and sills to Dionisio Park on the northwest tip of Galiano Island.

Dionisio Island is joined to the main island with a fine sand tombola. Approach from Porlier Pass (on the north side of the spit) to run up on the beach. Considerable effort has been put into developing the local campsite and trails, and there’s much to enjoy and walk, including numerous informative signs documenting the long history of the area by First Nations going back thousands of years.

And as an interesting side note, at Dionisio you are just north of the 49th parallel. A cairn on the west side of Galiano Island marks the spot where that significant line runs across the land. But for history, everything south of that line might have been Oregon Territory.

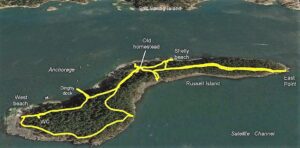

Russel Island

Elevation gain: minimal

Distance (return): 3 kilometres

After Captain James Cook’s exploration of the BC coast in 1784, a vigorous trade in sea otter pelts began, copying the Russian fur trade from Alaska, which had started half a century earlier. Even before commercial companies got into the game, Royal Navy officers cashed in on the high demand from China. There, they traded pelts for tea, silk and porcelain goods, which were then sold in Britain.

The Hawaiian Islands were the Navy’s winter stopover so it wasn’t long before Hawaiians (or Kanaka as they called themselves) were involved in the fur trade up and down the coast for the Hudson’s Bay Company. In the early 19th century they settled in Canada and the US, but when the US passed legislation preventing them from becoming citizens or owning land, many moved to the newly created province of British Columbia, where some settled the Gulf Islands.

In 1886 the Kanaka settler William Haumea received a Crown Grant for Russell Island, adjacent to his other prop- erty on Salt Spring Island. He cleared fields and planted an orchard, but didn’t build a house, preferring to row back and forth across the narrow channel between his home on Eleanor Point and the island.

In Haumea’s will, he left Russell Island to a daughter, Maria Mahoi, and in 1902 she moved there with her second husband George Fisher and their seven children, where they built a home, grew fruit and berries, raised sheep, cows and chickens, and supplemented their diet with fish, clams and other food from the sea.

The island remained in the family until 1959 when it sold to the Rohrer family, who held it until 1997, when it was sold to the Pacific Marine Heritage Legacy, from where it became part of the Gulf Island National Park Reserve. Today, descendants of the Mahoi/Fisher family have an agreement with the park to be at the homestead, where they tell stories to visitors during July and August, bringing a personal connection to settler history.

Drop the hook on the northwest side of the island in three to five metres with fair holding. This is a day anchorage with reasonable protection from a southeaster, but little from a northwester. The Fulford ferry passes periodically, so beware of wakes. There’s a park dinghy dock, or land on one of the small shell beaches.

Turning left (east) off the jetty brings you to the old homestead and nearby orchards in about 10 minutes. Much overgrown these days, the house overlooks a pretty white shell beach that is worth visiting. Just beyond the homestead on the east side, a faint trail leads into a forest of fir, maple and redcedar, bringing you to East Point in about 20 minutes. It’s a bit overgrown, but hopefully parks will clear it to make access easier, as the views from the grove of arbutus on the point looking east are superb, and very much worth the effort.

Retrace your steps, pass behind the house and make a clockwise loop along the shore to the west end of the island. There’s a sheltered shell beach looking toward Fulford Harbour, which is popular with swimmers, and a vault toilet inland.

The entire ‘circuit’ is barely three kilometres, with almost no height gain or loss. Russell Island offers good views, and a chance to embrace a fragment of local history.