IF THERE WAS a year recreational boating changed forever in British Columbia, it might be 1973 when Pacific Yachting began publishing a series of cruising stories written by Bill Wolferstan. With their aerial photography, excellent text and fascinating historic and cultural background, these stories—which became the basis of a series of guidebooks—opened up a cruising paradise that suddenly seemed accessible to anyone with a boat. Boat purchases surged and West Coast boating would never be the same again.

Wolferstan’s articles offered a unique blend of destination information that fascinated readers and helped make Pacific Yachting one of the most successful boating magazines in North America. The magazine’s editor at the time, Gerry Kidd, saw the potential of compiling these stories into a book and urged Bill to research more anchorages and background material for each of the three guidebooks Pacifi c Yachting eventually published.

For anyone cruising BC waters from the 1970s to the early ‘90s, Wolferstan’s books—which covered anchorages from Victoria to Desolation Sound—were essential additions to the ship’s library. Other than the Sailing Directions, there was nothing else available quite like them and they entered the collective memory of the time. Sam Burkhart, editor of PY, share’s his boyhood impressions: “My brother and I would be absorbed by Bill’s books. We loved the pictures and imagined cruising to what seemed remote destinations on a still wild coast,” he says. “Bill’s books combined just enough history to give the places a certain romance along with the useful information that made the guides really functional for boaters.”

EACH NEW VOLUME opened up another area of the coast and gave details on numerous nooks and coves for getaway anchorages. The large-format guides gave general information in the first 20 or 30 pages dealing with weather and sea conditions, geology, marine and bird life, and some historic background. The second part of the books delved into the destinations with details on passes, islands and anchorages while threading historic aspects into the text, giving the reader a sense of the thousands of years of First Nations culture and the arrival of European explorers. Bill included vignettes of pioneers, steamship captains, hand loggers, outlaws (and the sage judgments meted out to them) and the lonely lighthouse keepers who kept the coast safe for navigators.

Excerpts from explorers’ logs, such as those of Captain George Vancouver, were sprinkled throughout the guides and references to place names on the coast often included a bit of human drama. I can remember using the books to hunt for spots where Vancouver’s men might have found shelter for the night, or setting off by dinghy to search for the remains of a wreck Bill may have mentioned on a nearby reef. But it was his descriptions of the anchorages that just made you want to be at these places.

Duart Snow, PY’s editor for several years in the 1990s, says the impact of Wolferstan’s guides was central to the growth of boating in BC “‘Bill the Explorer’ nudged us into doing some exploring of our own, finding our own favourite spots. Even today, with their piloting advice and aerial photography, his books remain timeless as a navigational tool and remain among the best guides on the market,” Snow says. Indeed, all guidebooks to the BC south coast owe a debt to Bill’s guides, which are still referenced by boating authors.

THE STORY OF how Wolferstan came to create these books actually begins in 1970 when he was a graduate student at Simon Fraser University. While pondering what to do for his thesis in geography, Bill’s professor suggested doing something he would enjoy, which to Bill meant boating. But his love of boating didn’t come easy. After graduating from UBC in 1964 through the Registered Officers Training Program and serving as a lieutenant in the army for four years, Wolferstan moved to England where he worked at a boarding school for boys near Bournemouth. While there he found a 26-foot folkboat that he planned to sail to Vancouver.

Bill set off with a friend in late September to cross the Atlantic and hit a bad storm in the Bay of Biscay that dismasted Bill’s small vessel. His crewmate suffered a concussion and, after floundering for a few days, they took to a life raft (with papers and whisky) and watched as their little boat sank. Eventually, a Dutch freighter rescued the two men.

Bill returned to Vancouver and university to write his MA thesis. He and another student, David Oliver, received a $3,000 grant from SFU to buy a “research vessel” for their respective theses. In the summer of 1970 they sailed to Desolation Sound to research Bill’s thesis on “Marine Recreation in the Desolation Sound Region” and David’s on “Differences in Recreational Behavior between Sailboaters and Motor-boaters.” The time spent in the region in pursuit of higher learning, however, was not without incident.

Oliver relates how one day Bill decided it would be a good thing for them to climb up a mountain ridge on East Redonda Island to take a few photos. Problems arose after the two became separated on the way down and Oliver found himself on a ledge above a cliff. During his effort to extricate himself from his precarious perch, Oliver slipped and fell down the slope “half tumbling, half flying” past his astonished co-researcher some 30 metres down the incline.

“I had cut up one knee rather badly and discovered I couldn’t lift my leg to walk down the rest of the way to the spot where the boat was anchored,” Oliver recalls. “We didn’t have a radio so Bill climbed down the ridge and took the boat over to Prideaux Haven to find a boat with a radio and called the coast guard. They returned with a stretcher and got me down the slope and to a hospital. He saved my life, I don’t know how I could have got down that mountain without his seeking help.”

While working on his thesis back in the city, Bill attended a surprise birthday party for a young woman named Clementien Secker. Methodical in everything he did, he completed his master’s degree and convinced Clementien to marry him. After his research was published by SFU, he took the material to Gerry Kidd at PY and this became the basis of his feature stories in Pacific Yachting.

WOLFERSTAN’S RESEARCH IS also credited in the creation of one of the most renowned yachting destinations in the world when Desolation Sound Marine Park was established in 1973. With 40 miles of shoreline and over 20,000 acres of upland, it became British Columbia’s largest marine park. The result would have long-lasting benefits for boaters and the marine industry throughout the Pacific Northwest.

“Bill’s research was instrumental in the designation of Desolation Sound as a marine park by the provincial government,” Oliver states. To this day, Wolferstan’s ground-breaking research of Desolation Sound is still quoted by geography students, corporations and government researchers when discussing the use of foreshore, the waters of our coastline and environmental issues of the coast.

WOLFERSTAN’S FIRST GUIDEBOOK, on the Gulf Islands, was published in 1976. With its stunning aerial photographs and excellent maps hand drawn by Clementien, the book’s first printing quickly sold out. This was followed in 1980 with his book on Desolation Sound and, in 1982, with his title on the Sunshine Coast. By then Bill had an established career with the provincial government in the Ministry of Environment where he worked for 20 years, taking early retirement in 1999.

Paul Burkhart, editor of PY from 1980 to 1992, remembers working with Bill on the Desolation Sound and Sunshine Coast guides and says the biggest issue and cost was the aerial photography, shot mostly by George McNutt. “Ideally, these needed to be shot in fine weather during low tides, but sometimes neither cooperated and the results could be problematic,” he recalls. “Bill’s serialized excerpts of the guides in PY tended to boost readership, and I often met boaters cruising with photocopies of the magazine.”

Another former editor of PY, John Shinnick, also has fond memories of meeting up with Bill Wolferstan and recalls a time when he and Burkhart learned to appreciate Bill’s approach. “I met Bill one morning in a small anchorage along the shores of Bowen Island. Paul Burkhart and I had taken Missprint (the PY powerboat) over to meet him to drop off proofs or pick up something, I forget the reason for our rendezvous. What struck me was the niche Bill had chosen as an anchorage; it was the kind of spot that the vast majority of boaters would have overlooked and it became one of the main reasons I liked using his books.”

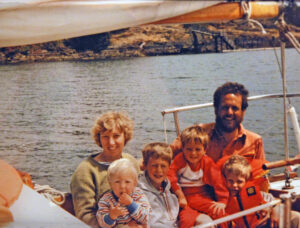

BILL’S APPROACH TO boating was modest. He eschewed the modern conveniences most boaters today take for granted. The small 22-foot sailboat he started out in with David Oliver was traded in for a Gulf Island 29, a rugged sailboat that had a depth sounder and radio and not much else. He travelled extensively with this vessel, called Tumbo, and, over time, added four children to the crew list.

His children, now in their 30s and with children of their own, look back fondly on the days when their father would take them sailing. Bill and Clementien’s favourite anchorages for the kids were Arbutus Cove on Chatham Island and Discovery Island, both close to their slip in Oak Bay. They also recall going to James Island and anchoring in the lee of the spit for summer barbecues in the sand. The youngest of Bill’s children is Elizabeth, who remembers being scared during some of the hairier moments of sailing. But she, like her three brothers, remembers just how happy her dad was when he was out in a boat. “He was peaceful out in the boat and liked doing funny things like wearing a tea cozy on his head when he couldn’t find a hat. I remember the way he smelled, campfire, rain, salt and his scratchy beard and a big smile,” she says. “Dad also liked to let us sit in the dinghy as it trailed behind Tumbo as we motored about and this was best because it was freedom.”

The eldest son, Jonathan, remembers the endless stories about the coast and how his dad loved to strike up conversations with people. “Even in France, he always wanted to talk to strangers when we had our canal barge. And he can’t even speak French,” Jonathan recalls and said his dad was always interested in local history. “He was a big fan of Captain Vancouver. I remember Dad saying Vancouver named Desolation Sound not for the gloomy weather but for all the abandoned First Nations villages.”

MATTHEW REMEMBERS HIS dad’s spirit of adventure and his love of this coast that was inspiring. “I have a memory of sailing somewhere, going north, just Dad and us three boys. We were sailing through some pretty serious weather, really heeling over, being a little scared but it was also thrilling. Sort of realising this was… serious.” Matthew and the other sons also remember a rite of passage when their dad would put them on a small deserted island overnight with meagre provisions and a log to write their thoughts. They also had a whistle in case they were in trouble or just wanted off the island.

Thomas is the youngest son and now has two children of his own and, like his other siblings, says his fondest memories were the trips to Chatham Island and James Island. But there was one trip that sticks in his memory. “I recall Dad taking us in Tumbo up one of the mainland inlets—possibly Howe Sound or Jervis Inlet. I remember vividly the howling of wolves and being quite concerned that Dad keep the companion-way doors closed! I thought they might find a way aboard and get down below I guess!”

IN TIME, THE popularity of Bill’s books faded as other publications came on the scene and the publisher of his books decided not to reprint them due to the cost of updating and a changing market. But, like other boaters who have cruised extensively, Wolferstan understood that the BC coast—estimated to be almost 30,000 kilometres in length—is unique in the world. Few other coasts are so complexly indented with bays, inlets, channels and archipelagos. When he set about to itemize the anchorages and destinations for each of his books, he gave boaters not only the where and how, but the all-important why go?

Perhaps the last word on his books can go to Ladner boater John DeJong who says, “It was like seeing something exciting happening outside when you were young. His books made you want to get off the couch and go sailing.”

“Life with Bill was, not always, but often enough an adventure,” says Clementien. “Without him in my life, I might never have sailed this beautiful coast, discovered Desolation Sound, learned to dig for clams (and eat them steamed and soaked in garlic butter), heard him blow a kelp horn, sailed in a Barbary Ketch from Holland to England and back across the channel and up the Seine to Paris, and spent 15 summers showing guests the wonders of France in our 1916 Dutch sailing barge.”

FANS OF BILL’S books will be saddened to learn that Bill is suffering from advanced Parkinson’s and has been in a care facility since 2013.