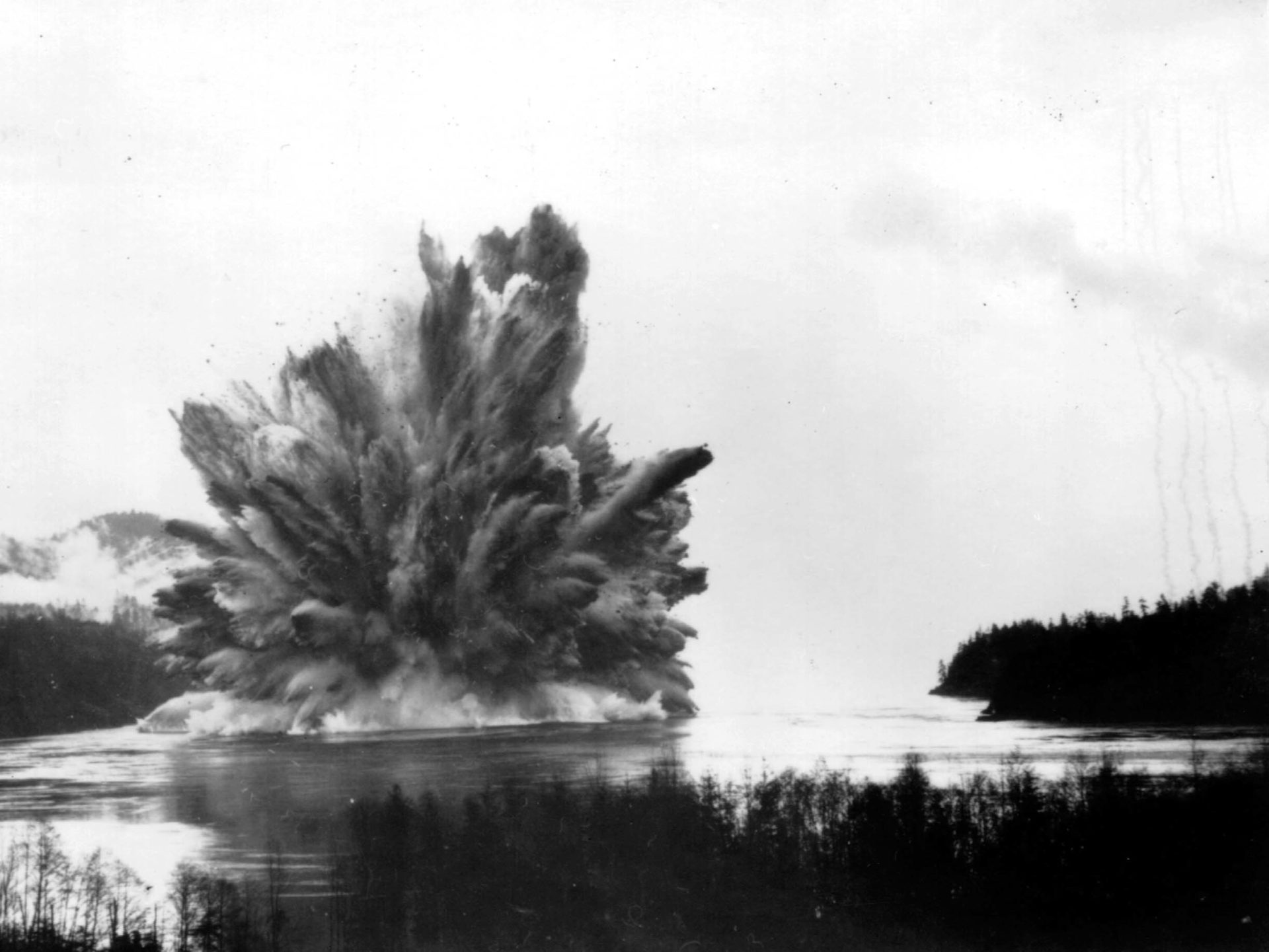

I first learned of Discovery Passage in 1958. We were home in Victoria glued to our 21-inch black and white television set listening to the CBC announcer count down from 20 to one when suddenly the once calm sea channel on the screen exploded into a mountainous spray of seawater, debris and noise. We had just witnessed the largest non-nuclear explosion to date—the destruction of the navigational hazard known as Ripple Rock.

It was not something a 13-year-old fellow was about to forget. It interested me enough to learn that Ripple Rock was (or had been) a twin-peaked mountain in the middle of Discovery Passage’s Seymour Narrows, a part of the busy marine route on the way to Vancouver from northern Vancouver Island and beyond. At low tide the rock peaks lurked just 2.7 metres underwater in the passage explorer George Vancouver described as “one of the vilest stretches of water in the world.” With Ripple Rock in place, he was right; over the years this deadly marine hazard had claimed 110 people, 20 large ships and 100 smaller vessels since the first recorded ship, the side-wheeler gunboat USS Saranac, went down in 1875.

The well-engineered Ripple Rock detonation took place on April 5, 1958 using 1,375 tons of explosives that were planted into the underwater peaks by tunneling horizontally from nearby Maud Island and then vertically into the rocky peaks. The explosion launched 635,000 metric tons of rock and water 300 metres into the air. The blast increased the low tide depth to 13.7 metres and 15.2 metres for the two peaks. I imagine there was a giant sigh of relief from coastal navigators knowing Discovery Passage’s main obstacle was no more.

In 1965 I learned that Discovery Passage still had some challenges waiting for unaware boaters navigating these waters. My summer job that year was janitor at Campbell River’s John Hart Dam site. As it was shift work it often gave me days off to go fishing courtesy of my University of Victoria pals working summers as guides at the famous Painter’s Lodge. When they didn’t have a customer they’d take me out on Discovery Passage in search of adventure and salmon.

Being 20-ish, male and fearless, it was heavy on the adventure part. By then I’d raced hydroplanes, cruised the Strait of Georgia in a 14-foot runabout and run powerful ski boats for years—but this introduction to natural hazards was different. Onboard speedy aluminum outboard fish boats, these ‘guides’ introduced me to things that would surely give me a heart attack today. I mean it.

These guys showed me first hand Discovery Passage’s wildly strong tides and currents, the insides of deep dark whirlpools, how to fly through back eddies all the while running shoulder to shoulder with vertical rock walls. And yes, we caught salmon as well.

These eye-opening experiences had the positive effect of encouraging me to learn more about natural hazards, how to safely navigate this stretch of water and had me digging into Discovery Passage’s history.

Navigating Discovery Passage

The 13.5-mile long Discovery Passage connects the Strait of Georgia to the south with the Johnstone Strait to the north. It averages one mile in width as it runs between Quadra and Sonora Islands to the east and Vancouver Island on the west. Where navigation gets interesting is in the Seymour Narrows, the 2.7-mile stretch north of Campbell River. Here the pass narrows to 750 metres and currents can reach 16 knots on a flood tide (south) and 14 knots on an ebb tide (north). It is recognized as the world’s third fastest tidal stream. Couple that with the fact the narrows is a busy pass used by freighters, enormous cruise ships, tugs pulling log booms, commercial fish boats and recreational vessels of all sizes and things can get interesting quickly. This is particularly so if you are travelling at any time other than within a half hour of slack water. As having witnessed myself, when the wind is up, eddies and swirls can get wild for small boats… be prepared.

Discovery Passage’s Rewards

While travelling Discovery Passage requires some forethought, the rewards for doing so are many. The currents we’ve discussed provide huge amounts of nutrients and oxygen to support many species of fish, invertebrates and even the elusive giant Pacific octopus. But most notable over the past century has been Discovery Passage’s legendary salmon fishery that earned the city of Campbell River its title as the “Salmon Capital of the World.” The title lives on if not slightly subdued from the days this much younger student fisherman came on the scene.

Painter’s Lodge

Campbell River’s famous Painter’s Lodge was made of wood when I arrived in 1965. Corky Corbett, the uncle of one of my fishing guide pals, owned it back then. The resort started as a group of tents and then a few cabins were added before the main wooden lodge was built in 1940.

Located near Frenchman’s Pool and Tyee Pool, Painters Lodge became world famous as a fishing destination when celebrities like John Wayne, Bing Crosby, Bob Hope and Susan Hayward started arriving. I recall ogling the impressive celebrity-filled collection of black and white photographs covering the walls of the lodge’s stairwell. I was saddened when the original lodge burned down on Christmas Eve 1985 along with its photo collection.

A few years ago I visited the new Lodge built in 1988 to find some photos back in place to illustrate the history of local salmon fishing with emphasis on the Tyee Club of BC.

The “Almost” Tyee Club Member

One of the more exciting hours of my fishing life occurred when a guide pal introduced me to tyee fishing. Tyee is the name given to a chinook or king salmon whose weight exceeds 30 pounds (13.5 kg).

Tyee Club member wannabes must obey the club’s regulations stipulating that a caught salmon must weigh a minimum of 30 pounds. It must be hooked with a barbless, artificial single-hook lure fastened to a maximum 20-pound (nine-kilogram) test line. Lastly, you must fish using a rowboat. On this evening my guide pal rowed while I dragged the waters near the entrance to the Campbell River.

Thirty minutes out, it happened—I got a strike so sharp I almost lost the rod. For the next half hour my guide struggled to keep the boat in position while this amazing creature at the end of my line pulled us northward for a quarter mile. Other tyee fishermen called out encouragement as we cruised by in our one-fishpower rowboat. And then the line suddenly went limp. My guide hollered, “Reel in!” and I did as fast as I could but the line suddenly stretched taut then snapped. Once I got off my you-know-what having planted it on the bottom of the boat, we headed to the lodge’s bar to toast the one that got away. I was buying.

Since those early days I have cruised, travelled and visited Discovery Passage waters and ports many times. On each visit the memories of those long-ago experiences come up as fresh as the day I lived them, every time.