It was the writer P.J. O’Rourke who mused that there are lots of mysterious things about boats, such as why anyone would get into one voluntarily. Getting off one is more understandable, certainly. We try, whenever we’re boating, to get off at least once a day. South of the rapids that separate the Salish Sea from “the north,” it’s easy. There are beaches, trails and roads aplenty. It’s not hard to find a place to stretch your sea legs.

North of the rapids, of course, is different. Roads and trails are few, and grizzlies are plentiful, so most walking opportunities are along beaches. When coming ashore on a sandy bay, follow Hudson’s Law: Always land at the mid-point of the beach. That way, you only have to run half its length when pursued by a bear.

South of the rapids, there are lots of great hikes. Here we’ll look at six favourites in the southern Gulf Islands, all of which offer great views regardless of how far you want to hike. Stop early, and there are still great views. Go to the top, and you have the satisfaction of seeing the world at your feet.

Hiking boots on? Sunscreen at the ready? Let’s go.

Mount Tzouhalem’s Southern Ridge

Height gain: 536 metres / 1,770 feet

Distance return: 3 kilometres / 1.9 miles

Genoa Bay is a popular overnight spot for cruisers. The harbour provides good shelter, and the bay is moderately protected from wind, apart from southeasters that can sneak in and make things rolly if you are at anchor. The Genoa Bay Cafe offers interesting bistro style food, local wines and fine dockside breakfasts. The float homes are charming and provide a good opportunity for photographers who may want to snap their funky colours and flowers.

Another good reason to visit Genoa Bay is Mount Tzouhalem, which towers above the bay on the west side. Follow Genoa Bay Road up from the marina to where it meets Saltspring Road. Directly across the street, a trail leads into the woods. Follow as it curves right and then back left to avoid private property, before climbing steadily through maple, fir and arbutus. In summer, the shade is welcome.

After about 15 minutes, avoid a side-track that climbs steeply to the right. Follow the gentle climbing track straight ahead to the prominent ridge that runs down from Tzouhalem’s summit. As the trees thin, the views south down Satellite Channel past Separation Point just keep getting better and better.

After you reach a spot where you can see into the Cowichan Bay river delta, pick up a larger track coming up from the west side of the mountain. Follow this up to the right through stands of small Garry oaks. In the spring, the meadows are covered in flowers—camas, shooting stars and satin flowers. The trail is wide and obvious, and the nice thing is you can go as far as you like up the ridge. Ninety minutes will bring you to the summit (536 metres), but you don’t need to go that far. There are plenty of grand views lower down, including a handy bench at the 400-metre/1,300-foot mark that provides a good turnaround spot.

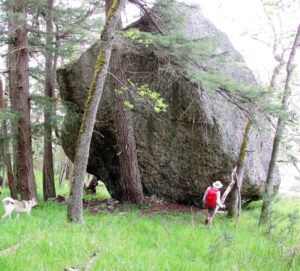

On the descent, look for a track to the left at about 140 metres elevation that leads to a viewpoint where you can look down into Genoa Bay—“Oh look! There’s the boat!” A little lower down on the main track through the Garry oak forest, look left for a boulder the size of a large house, off the trail. A track leads to it.

Mount Tuam’s Broad South Flank

Height gain: 560 metres / 1,850 feet

Distance return: 3 kilometres / 1.9 miles.

Mount Tuam is the southernmost peak on Salt Spring Island, and boaters pass it frequently as they transit Cape Keppel. Anchoring at the point is a problem. There’s no shelter, the currents along Satellite Channel are strong and wakes from passing boats make the prospect of dropping the hook unpleasant. It’s best to duck into Deep Cove across the channel on the Saanich Peninsula and anchor near the back of the bay. Then it’s a short 10-minute run in the dinghy or 30-minute paddle in the kayak to Salt Spring Island.

An obvious public road comes down to the shoreline just east of Cape Kepple. Walk up to meet the service road that parallels the coast. Bearing slightly right, plunge into the arbutus forest (there’s no official trail, but the forest is open) which after about 150 metres of elevation gain brings you into a spectacular meadow that sweeps up the slope to the summit at 560 metres elevation.

Spring is the best time to visit of course, when the grass is carpeted in flowers, but any time is good because, as you rise, the views in every direction just keep getting better and better. If it’s a hot summer day, angle up to make the best use of the shade from the broad, spreading Garry oaks that dot the slope. From the top, you can see snow-covered Mount Olympus in Washington State to the south, Mount Baker to the east and, if it’s very clear, Mount Ranier to the southeast. Closer to hand, there’s Haro Strait full of shipping, the City of Victoria, Saanich Inlet and all the way west to Cowichan Bay.

Like Mount Tzouhalem, if you’re not feeling energetic, just go as far as you feel inclined, find a flat spot and enjoy the panorama at any elevation.

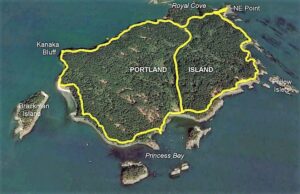

Around Portland Island, or Not

Height gain: 25 metres / 80 feet

Distance: 7.5 kilometres / 4.7 miles

Portland Island is a perennial classic. No height gain, and you can make the walk as long or as short as you want. The entire circumference is 7.5 kilometres (~2.5 hours), but if time or energy is low, make use of the trail that runs north/south across the island, and do just one half or the other. My preference is the east hemisphere. Walk through to the north shore and then follow the east shore back, passing the beautiful northeast point with its sand beach and shell tombolo. The east side of the island has a number of little sandstone headlands and enclosed beaches that are worth visiting. The trail stays close to the shore so sea views are possible much of the way.

Anchor in Princess Bay behind the Tortoise Islets (crowded at weekends). The bay is shallow (less than five metres) so the bottom has a lot of weed. Make sure you’re attached to the mud, and not just the kelp! There’s a dinghy dock in the summer, or run up on the beach at the head of bay. Interpretive signs tell the history of the island when it was a working farm. In the 1980s, feral sheep kept the grass cropped like a golf course across the island, but National Parks have removed them, and now some of the rarer Gulf Islands flora are making a comeback. Look for sedum, larkspur, satin flowers, white and blue camas, monkey flowers and the rare yellow-flowered cactus on southern dry slopes.

The island was used by First Nations for millennia. Large middens are apparent everywhere along the shores. Later, Hawaiians farmed it in the 1880s. In 1958 the island was given to Princess Margaret, sister of Queen Elizabeth, in the days when ex-colonies still did that sort of thing. In 1967 she donated the island to BC as a park and it has recently been incorporated into the Gulf Islands National Park Reserve as one of the few islands wholly inside the Park.

A Forest Walk on Sidney Island

Height gain: Negligible

Distance return: 3 kilometres / 1.9 miles

The north end of Sidney Island is part of the Gulf Islands National Park and home to Sidney Spit, a mile-long stretch of sand and sun-bleached logs that is a popular destination for many boaters in the summer. As the tide rises and falls, so too does the mid-section of the spit disappear and reappear. There are park floats, a park dock, a popular park campground and a regular summer passenger shuttle from Sidney across Cordova Channel.

Most boaters who want to stretch their legs will turn left off the dock ramp and walk the spit, but there’s a pleasant alternative that gets you away from the crowds and, in the summer, offers the luxury of a cool walk under tall trees, rather than on dazzling sand.

Take the trail less travelled and bear right off the ramp, following the signs to the campground. After a hundred metres (at the vault toilets) turn sharp left and follow the edge of the cliff to its northern tip where there’s a fine viewpoint looking up the spit from the height of land.

Thereafter, follow the wide trail along the east side of the island, above small sandstone cliffs (there’s a midden too, for the sharp-eyed). At low tide, the beach on the east side of the island is always less crowded, and is very safe for children, as the water is shallow for a long way out. Here and there, stairs lead down to the water.

Much of the forest you are walking through is second growth, with the first growth cut to stoke the brick kilns which occupied the north end of the island from 1906 to 1915. Happily, in the past century many fine trees have re-established themselves. Look for the common Douglas fir, big leaf maple (with massive trunks), redcedar and arbutus, but also the rare Pacific yew and the even rarer Douglas maple (which is seldom higher than 15 metres/50 feet but has the same iconic leaf shape. The Gulf Islands is one of few places that you’ll find them).

The trail leads back from the east side to the west, coming out into the kind of meadow that dogs dream about. If you turn left here and follow a road south, after about 10 minutes cut down through an area of tussock grass and scattered trees, where the forest hasn’t quite taken back the meadow, and you may find a curious object. It’s a mound of grass and earth a little taller than a man, with two cinder block entrances.

The local myth is that it was a bomb shelter, but from which era? In the First World War, there were workers nearby in the brick kilns, but no aeroplanes. In The Second World War there were aircraft about, but nobody on the island. The most likely explanation is that it was a powder magazine for the clay works. Perhaps they needed to loosen the hard pack occasionally?

If you aren’t interested in old shelters, skip the road south and instead cross the meadow east to west, making a shorter loop. The campground is the site of the old brickworks where they quarried the fine clay. There are interpretive signs, bricks aplenty at the tideline, plus a jetty where you can watch waterfowl in the lagoon, and purple martins nesting in boxes overhead. After leaving the campground to return to the dock, look on your right close to the trail for half a dozen very tall cottonwoods with their deeply scored bark.

Mount Norman’s Viewing Platform

Height gain: 240 metres / 790 feet

Distance return: 6 kilometres / 3.8 miles

This peak dominates Bedwell Harbour and Poet’s Cove, and is a popular hike. Montague Marine Park is a favourite with the cruising crowd, so it’s not surprising that Mount Norman gets numerous ascents daily in the summer.

From the beach behind Skull Islet follow the wide trail that parallels the shoreline north through Douglas fir and maple for 1,500 metres, the cliffs above the sea to your left gradually getting higher. At that point, the trail curves uphill and the climbing begins, as you gain a ridge and then, sadly, lose height on the other side, to meet an old logging road. From there, a steady plod up Mount Norman’s north spine gradually gains height until after 800 metre a turnoff to the right brings you out to a viewing platform.

All of Bedwell Harbour lies below your feet, while the vista stretches past Moresby Island to Victoria and Juan de Fuca Strait. On a clear day, it’s a superb panorama that’s worth the rather circuitous U-shaped route to get there.

Apart from the trail being rather indirect, there are few views once you leave the shore, until you reach the platform. This lack of aesthetic appeal bothered me for a long time. Finally, after looking at the face of Mount Norman that overlooks Bedwell Harbour for years, a friend and I (both experienced climbers) scrambled directly up from the beach, a short, steep but exhilarating ascent which I don’t recommend unless you are comfortable on precipitous grass ledges and loose rock. Only when we reached the platform at the top did I notice that my friend had climbed the entire route in crocs!

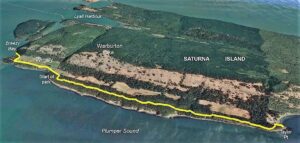

Saturna Island: A touch of the Med

Height gain: 50 metres / 160 feet

Distance return: 12 kilometres / 7.5 miles

A wonderful hike leads past the Saturna Island winery into Taylor Point Protected Area, a long, thin park that encloses the shoreline overlooking Plumper Sound. Although quite long, the height gain is minimal, and the trail is both easy and interesting, bringing you out at a ruined stone farmhouse at Taylor Point.

Anchor in Breezy Bay (fair weather only) and come ashore to pick up the public road that leads round the bottom of the vineyards. For about 1.5 kilometres you pass private homes on the right, between you and the sea, before reaching the Protected Area. Through the gate, the trail turns to the right towards the sea. It then follows the top of the sandstone slabs and cliffs, under Douglas fir and arbutus a further 4 kilometres to Taylor Point. Hike as near or as far as the mood takes you. The aspect on a sunny day, under the shade of tall trees with the blue water glittering100 metres below is one of the best examples of Gulf Island hiking, and puts me in mind of the Mediterranean coast.

At Taylor Point, an old stone farmhouse built in 1892 stands as a crumbling reminder of the hard lives early settlers had. British-born George Grey Taylor and his wife Anne created a life on 100 preempted acres on that isolated point of an isolated island. Separated from others on Saturna by the steep hill, they were truly self-sufficient while raising five children. There were apple, pear and cherry orchards, and George, a stonemason by trade, cut sandstone to build their home in traditional Lancashire style. In the surrounding fields were cows, sheep and chickens, while the sea provided crab, clams, cod and salmon. Later, quarried blocks were sold for the construction of several buildings in Victoria. Sadly, the house was destroyed by fire in 1932. George died the following year, but Anne lived to 90 on nearby Pender Island.