After some 20 miles of flying our older, rather oversized spinnaker up Principe Channel (with only the two of us on board) it was time to gybe. Underhanded sailing being what it is, we opted to pull the spinnaker into its sock, gybe the main, and start the engine. As soon as we were underway the engine coughed, then quit.

We record engine hours in our log and so we knew our tank was still at least 30 percent full. We “definitely” had not run out of fuel. Within the past year we had replaced all the copper gaskets in the banjo fittings of the diesel fuel system as part of a relatively thorough overhaul. The engine had been running smoothly. In fact, a week earlier we had motored into the magnificent Gardner Canal, perhaps 50 miles each way, without any issues.

Immediately, Al bled the engine and fuel filter. The engine started, then quit again. With no engine, we got creative with our sails, and slowly made our way into a known anchorage where we could better assess the situation.

We are both lifetime sailors. As well as many miles cruising the BC Coast, we have sailed to Spitsbergen, spent several summers in Scotland, sailed south to Cape Horn, through the inside passages of Chile, among the Pacific Islands, and from Japan to Alaska via the Aleutians. We have learned to expect the unexpected and manage without assistance. A tow was out of the question.

For the next three days we proceeded slowly with multiple sail configurations. We anchored under sail and hauled up our anchor by hand. We made headway during the lulls by strapping our inflatable with its eight-horsepower outboard to the side. Finally, we reached Prince Rupert where—for a mere 17 cents and a free ‘O’ ring—we replaced the bleed screw, (now a standard 10-millimetre machine screw) filled up the tank and ran our engine.

We spent another two weeks cruising the wild lands of the Central Coast without any issues until (in early August) we opted to meet some friends in Shearwater. We took the shortcut through Meyers Passage, a shallow, narrow channel with strong currents and rather thick kelp patches; a place where you would not want your engine to quit. Ours purred along as usual as we transited the channel, then we rounded the point just north of the narrow slot that leads south to Klemtu. At this point the engine coughed and quit! We were thankful for the extra half hour!

We were so “done” with analysis that we simply set sail and proceeded to beat south into a healthy breeze. Klemtu Passage is less than 150 metres wide, meaning we got only about 10 boat lengths per tack. In total, we tacked 44 times for 60 minutes, roughly 90 seconds per tack. We scarcely trimmed in before we were readying to tack again. Repeat and repeat. The track on our MFD was marvelous, and we were left exhilarated, but exhausted.

But what was the issue with our engine?

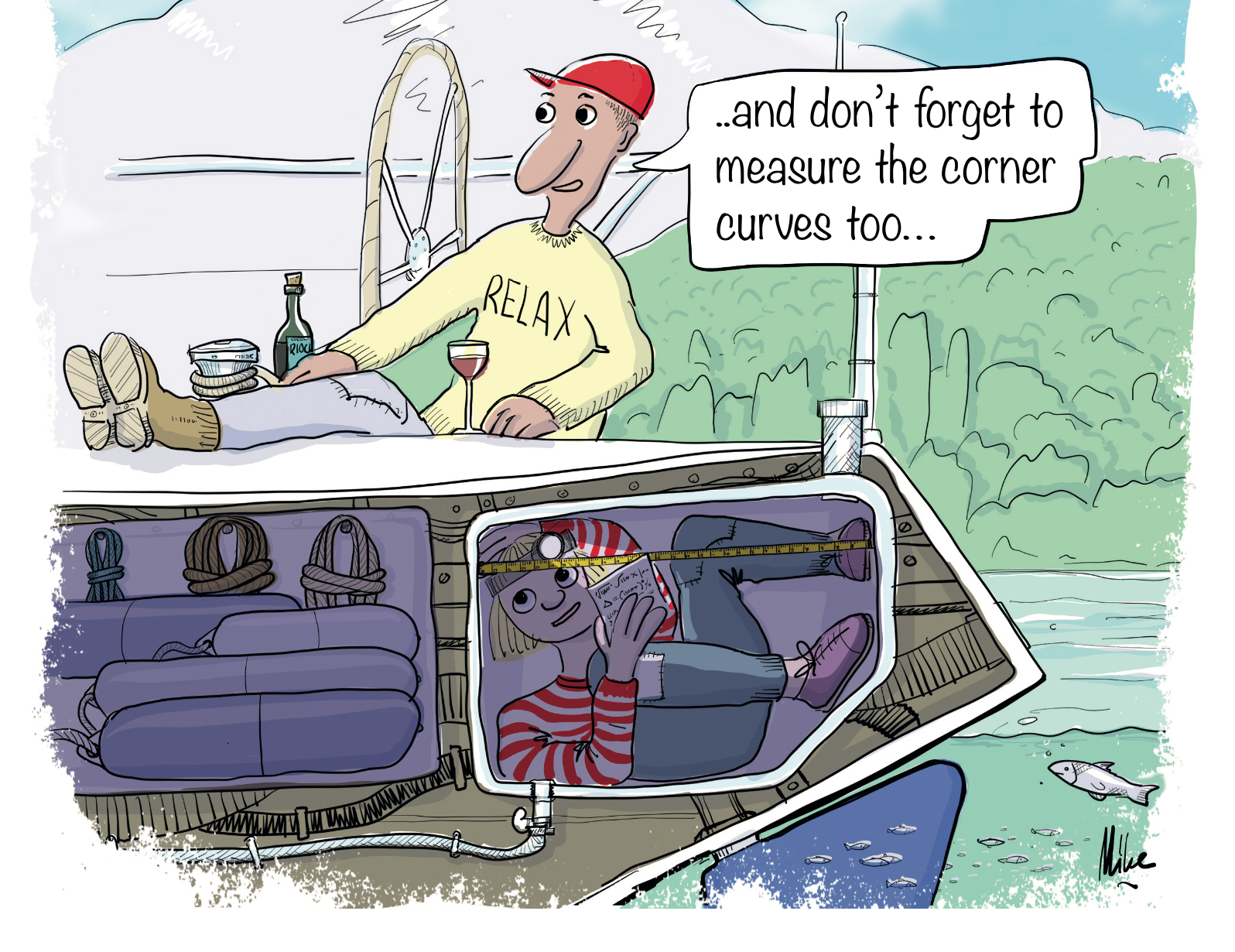

This was our fourth summer on our 1983 C&C 37. We regularly top up our fuel tank and tend to keep it no less than half full. We record engine hours, fuel consumption, and all fuel fills. Our purchase agreement and survey confirmed the fuel tank holds 30 gallons. During the night an unlikely tool for analysis came to mind: a tape measure. Sure enough, after repeated measurements, compensating for curved corners it became obvious that the tank held only 20 gallons (80 litres) not 30 gallons (120 litres)!

We were guilty of believing a document which listed our boat with a 30-gallon fuel tank, although the boat only has a 20-gallon tank! Usually quite vigilant, it took us four full summers (almost 20 months of full-time cruising) to discover this simple oversight.