This past summer my wife Mary Anne and I shared Traversay III, our 43-foot steel cutter, with our daughter, son-in-law and four grandchildren in a cruise through Gwaii Haanas National Park. I managed to make time to visit all the special sites (even the memorable but rather exposed SGang Gwaay Llanagaay) around the ever-evolving Haida Gwaii weather. Through all the good times though, I was aware from SailMail grib files that a monster low was coming and I needed a plan to deal with it.

A few days before its arrival, the Environment Canada forecasts began to warn of a 50-knot southeasterly storm forming in Hecate Strait. The westerly to follow was expected to be somewhat gentler but by no means benign. I had some ideas for a safe anchorage but settled on Hutton Inlet after a chat with a local charter skipper at Hotspring Island. The inlet had a short fetch, seemed oriented for protection from the southeast, was said to have excellent holding and was large enough that a dragging anchor would leave room to react. As is typical of northern British Columbia waters, there were no neighbouring boats to run into, but also no one to help if we did get into trouble.

While the southeaster the first night was predictably violent, we did not move—and the eased wind during the day allowed us to congratulate ourselves on our clever choice of anchorage. The night that followed was an entirely different sort of experience though as the barometer rapidly rose and the westerly spilled across a mountain gap from the Pacific. My midnight crawl across the rolling wind-pummelled deck to the bow to check the snubber for chafe prompted one of the children to alert my wife: “Granny, there’s someone outside!” Near 03:00, our GPS anchor alarm went off to announce that we were no longer where we should be. This was followed by oilies for Mary Anne and me, starting the engine, powering up the cockpit chart plotter and then… the anchor had reset and held us after dragging for about 50 metres. I stayed dressed and watched the chart plotter the rest of the night until conditions began to moderate.

Even in our sheltered inlet, our wind log showed a peak of 55 knots at about 03:00. We discovered later that three boats in other inlets had been dragged aground. Watchmen in the park said it was one of the worst storms they had seen—and in August of all months!

So is there a better way to deal with this? Well, there may be!

In Southern Patagonia the weather is frequently much worse than on the BC Coast—even the winter BC Coast. More than half the suggested anchorages in the cruising guides for that southern region involve shore ties; often three and four-way shore ties. In BC, shore ties are often used, particularly in marine parks, but they are used to eliminate swinging and to allow more boats to fit in an anchorage. In Patagonia, they are used, even by mid-size coastal freighters, to tuck a boat so close to the trees that 70-knot williwaws from changing directions can’t imperil the vessel by ripping its anchor from the seabed. With three or four (sometimes more) shorelines, the anchor is only involved in the initial arrival thus the quality of the holding ground is less important. In southern Chile, sailors say you will only sleep soundly with four lines attached to stout trees.

So how does this work? First you need a small V-shaped or (even better) U-shaped cove that has no fetch inside and minimal fetch into the opening. Place the anchor in the entrance such that you use the maximum amount of chain available without running out. Back as far as possible into the cove while letting out chain. One crewmember then uses reverse intermittently or, if the anchor is holding well, simply stays in reverse while lines are run out on each quarter to trees and then tensioned on cleats or winches. A single shore line aft will not work as the rocks will not be far away to the sides and you must prevent the boat from moving laterally. The time-critical part is now done and, if holding is good and weather not too threatening, you are finished.

So what’s the catch? In fact there are many. Four shore lines in a tight cove takes as much as two hours to rig depending on undergrowth, shore slope and weather conditions. So you need not bother except in the worst storm conditions. Of course if you haven’t tried it on a good day, you will not have the confidence when a bad day comes so it’s worth it to practice beforehand.

It is also difficult to find a good spot for this exercise. The tidal range in southern Patagonia is less than in BC. This means that, for a shore slope you can scramble up, the trees in BC will be further away and the cove larger—meaning longer shore lines.

A scan of our charts quickly found two suitable spots in the middle part of Gwaii Haanas. I rejected one, backing away at the last minute when I found the entrance shallower than the chart suggested. We used a four-way tie in the other, a small unnamed cove immediately south of Bigsby Inlet, and we stayed for a couple of nights with a day of SCUBA diving in between.

Some extra equipment is needed. Given that the stern lines are usually shorter than the bowlines because of the shape of the cove, two 50-metre lines and two 100-metre lines are probably a minimum. A few dock lines tied together can substitute for one of the stern lines. Patagonian sailors typically use polypropylene. It is cheap and, since it floats, it will not get as tangled in rocks and kelp.

Tips A few tricks can help.

- An initial relaxed reconnoitre of the cove can reveal easily accessible trees for the first two lines. On the actual mooring run, you will be in a hurry as the boat may be drifting toward the all-too-near shore so you will want to tie these lines quickly. You can always move them later to better trees that won’t break or fall down in a storm.

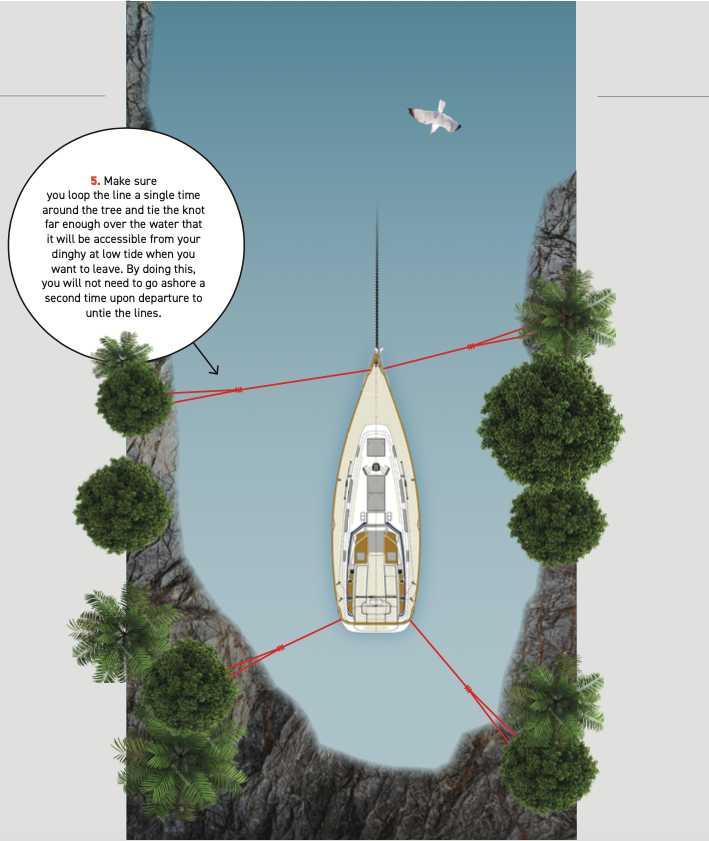

- Make sure you loop the line a single time around the tree and tie the bowline far enough over the water that it will be accessible from your dinghy at low tide when you want to leave. By doing this, you will not need to go ashore a second time on departure to untie the lines.

- If only one person is in the dinghy, you’ll need a very long painter (attached to you) or a dinghy anchor on shore so you do not lose the dinghy while you are climbing up to the tree.

- You’ll want to feed out the line as quickly as possible as the dinghy moves toward the shore, so the first two lines should be on reels or stuffed (not coiled) into bags.

- For areas with no trees, having aboard a few six-metre chains or wires along with some galvanized shackles will allow rocks to substitute for one or more trees.

Will this work for you? If you can find a suitable spot, you must balance the risks of clambering up a rocky shore and through underbrush against the risks of dragging anchor in a storm. During a 50-knot winter southeaster in Haro Strait, we were snugly tied to three lines at the inner end of Portland Island’s Royal Cove. After a night that saw widespread destruction on the land, our only result was a deck covered with pine needles. Even cruising the storied waters near Cape Horn, we never worried when we were tied this way, no matter how horrible the weather.