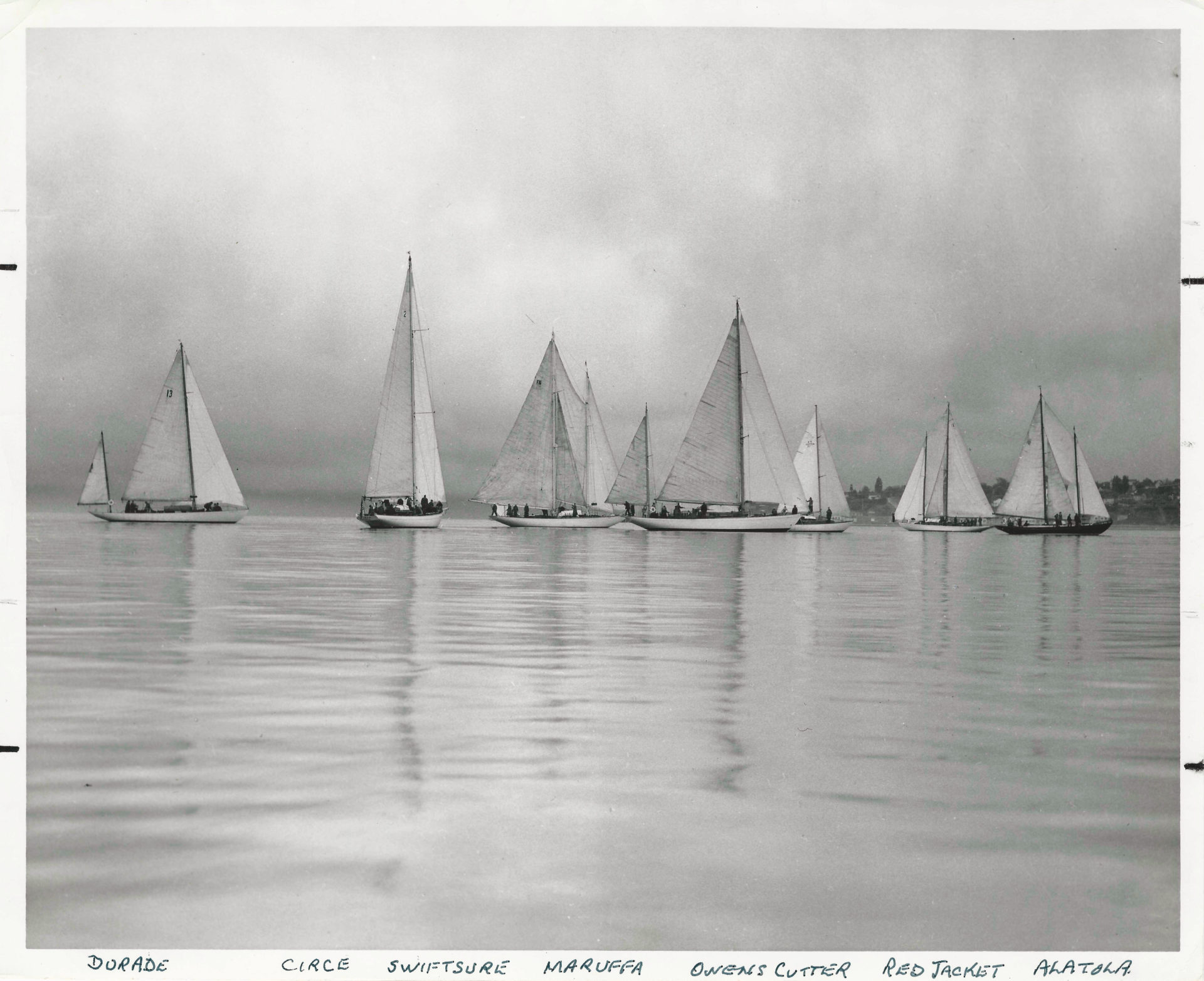

Feature photo from left to right: Dorade, Circe, Swiftsure, Maruffa, Owens Cutter, Red Jacket and Alatola. All black-and-white photos by Kenneth Ollar.

Let’s travel back to July 4, 1930, when several nattily dressed gentlemen, in dark suits, wide lapels, fedoras and certitudes, met to organize the first sailboat race that would become Swiftsure. They represented the geographic triangle of the three premier regional yacht clubs—Royal Vancouver, Royal Victoria and Seattle. After quaffing hot rums at the Royal Vic Clubhouse, they decided to race the next day from Cadboro Bay to rounding the Swiftsure Lightship moored on Swiftsure Bank. Indeed, six boats, Claribel, Westward Ho, Minerva, Andy Laili,Cressetand White Cloud took off at 11:00. Seattle-based Ray Cooke’s Claribel, a schooner, won.

The Race, named after the lightship and bank marking the entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait, was held again in 1931 and 1934, but the Depression and World War II prevented further contests until Royal Victoria’s Jack Gann revived the concept in 1947. That year, 15 yachts gathered in Victoria Harbour to race to Port Townsend. Royal Vic has continued to present Swiftsure every year since and, to accommodate yachts arriving from as far away as Oregon and California, and because July winds are often iffy, the long U.S. Memorial Day weekend in May was chosen as the race date.

Widely known as the premier long distance race in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. Like every year, there’s hope for a race that lives up to its name—swift winds, manageable tides, a sunny day without fog, an alert crew, and a boat without breakdowns that could hamper success, like this one.

Seattle’s Kurt Hoehne crewed aboard Voodoo Child. “We were over the line early and a competitor yelled that fact to us across the water. Our radio wasn’t working, so we didn’t get the ‘official’ word and sure weren’t taking the word of a competitor. We sailed a helluva race, would have won it, but when we turned up at the inspection dock they said, ‘Sorry, you’re a did not start.’”

If the founding racers could time traveland climb aboard the anchored Naval ship that signals the starts off Clover Point in Juan de Fuca Strait—perhaps with a few moth holes in their wool vests—they’d be astonished by how many permutations and adaptations Swiftsure has undergone over the past 88 years.

Yacht technologies have changed greatly. Navigational aids, communication methods and safety requirements have transformed sailboat racing. So have the numbers and sizes of sailboats participating, and the length and variety of races offered with trophies to match. And thousands of participants have left a legacy of personal adventures and photographs.

We’d certainly recognize the gentlemen’s 1930s wooden boats leaving Victoria Harbour, with their varnish and hemp. Their sails weren’t battened; most yachts were gaff rigged with cotton or linen mainsails, jibs and staysails. But our time travellers—undoubtedly invited aboard the Royal CanadianNavy ship issuing the start signals—would likely be delighted by the more than 200 yachts looping around while awaiting the start of their particular race in today’s contests. They’d gawk at the sloops, ketches, catamarans and trimarans of all sizes with their gleaming white, golden, silver or black sails as they jockey for position.

The commercialization of fibreglass boats made wooden boats mostly obsolete. The ability to mould hulls and decks allowed for faster and less expensive fabrication, and mass production and lower costs “democratized” boating. In Canada, the most influential fibreglass boat builders in the mid-‘60s were Grampian Marine, Hinterhoeller Yachts and C&C Yachts. “Few wooden boats are now in the mix,” said Doug Fryer, a veteran Swiftsurer with 50 races under his PFD. “My cold-moulded Nightrunneris one of the few boats not made of plastic.”

In the 1980s, synthetic fibres began replacing the “duck” sails made of cotton, hemp or linen. The new materials are more UV resistant, minimize stretching, rip less frequently, and last longer making them more cost effective. Materials used to build sails include nylon, Kevlar, polyester, Spectra, and carbon fibre. But even today’s fabrics aren’t foolproof.

Rob Adams, crewing aboard The Pitt, recalled the yacht being in a hurry to clear Race Passage before the tide turned. Suddenly, the spinnaker tore. “We were ready to call it quits,” said Rob, “but the skipper, Mike Litwin, snapped an emphatic ‘No! We’re going to sew it up.’” “Do you have any thread?” asked MD James Houston, who knew about sewing professionally. So while the skipper steered, five of us used waxed thread to stitch the spinnaker back together. Only minutes later, spinnaker aloft, she sailed beautifully.

Halyards, sheets and other lines have also gone high tech and have replaced the heavy hemp and manila ropes of the past. Instead of fibrous plant material like cotton, linen, coir, jute and sisal, today’s cored synthetic lines combine such materials as aramid fibre, Kevlar, Technora and Vectran. These heat-resistant synthetic fibres are prized for their low stretch and high strength.

Over the decades, Swiftsure changed its rules by adding racecourses so that smaller boats could compete. In 2018, Swiftsure will include six racecourses, all starting at Clover Point. The longest, and most traditional, is the Swiftsure Lightship Classic, the 138-mile long distance race. The Hein Bank race, added in 2015, measures 118 miles and travels to NeahBayand ODAS buoy 46088. The Cape Flattery Race was added in 1962 and runs 102 miles to Neah Bay. The Juan de Fuca Race, at 79 miles, sails to Clallam Bay. The Inshore Race is determined by wind, weather and currents on the morning of the contest; it typically runs along the waterfront to Williams Head. In 2018, one additional competition, the Classic BoatsRace, will be added—it will be a Saturday race and have an inshore course.

“If you’re a sailor, you must race Swiftsure,” said Rolf Schmidt. “It’s the spirit of being out there with wind and waves. I’ve participated in at least 28 races, finishing 25 and only the weather kept us from completing them all. My 1974, 30-foot Sparkman & Stephen’s designed Northstar, Tokolosh,won in 1995. My boat is named after a South African Zulu leprechaun who comes after children. So when another boat is in front of me, I say, ‘look out, Tokoloshis coming to get you.’ What I like about Swiftsure is the preparation, the camaraderie and that the variety of the courses allows smaller, older boats to compete. It’s not just for the hotshot big sleds, but also for everyday sailors who must spend their money wisely. For me, I’d rather buy something for the boat than go out to dinner.”

Evolving Communications In the post-war years, Swiftsure’s chair Jack Gann negotiated the use of Eaton’s display window to serve as “Swiftsure headquarters” at Douglas and View in downtown Victoria. The racecourse was laid out on a large map and miniature boats were shifted across the map to show race progress. Victorians appreciated the graphic display and would line the sidewalks or sit on the curb. A feeling of excitement about the yacht race pervaded.

Jack Gann introduced the first on-the-water radio broadcast in 1957, with Humphrey Golby’s booming voice becoming the “voice of Swiftsure.” Humphrey, who’d raced his first Swiftsure in 1934 aboard Circe, broadcast through the “Fisherman’s Band” from first-light-to-first star to the Eaton’s window. His voice was heard above all others; he was never at a loss for a race story or quip. Humphrey continued his broadcasts into the ’80s. Here’s how Gann got some of his information.

For 35 years, Bob Smithaboard his Ed Monk, Sr. custom-designed Scot Free, along with Gerry Williams on sister ship Shelimar, reported back to Swiftsure headquarters on the progress the sailboats were making. Swiftsure used a numbered grid to identify the yachts’ locations. “The first year, in 1972,” said Bob, “we anchored off Clallam Bay and tracked the boats as they rounded the mark. The following years, we’d roam all night up and down Juan de Fuca and when we’d sighted a few boats, we’d call the Sheringham Coast Guard station on the High Frequency radio and ask them to patch us through by phone to Swiftsure headquarters. I think the frequency was 2182 (today’s VHF 16). The Navy ‘Gate vessel’ on Swiftsure Bank would also call us on the HF when yachts rounded her and we’d relay the info. In the ‘80s, we used a single sideband radio to transmit the boats’ progress and later, we called in locations by VHF. When SPOT transponders became the norm in 2006, our powerboats retired from Swiftsure.”

But some traditions persist despite the advent of electronics that help track racers.

“I recall when we moved little paper boats on the (plywood) grid board as their locations were transmitted to us,” said Charlotte Gann, who’s volunteered as a Swiftsure organizer since 1978 and likely knows more Swiftsure history than anyone. “Today, Swiftsure still uses a grid map for communication between yachts and the race committee, while the SPOT transponders pinpoint yachts that are superimposed on a Google Maps image. Vessel Traffic Services still uses the ‘analog’ paper grid map to advise racers of commercial traffic in the shipping lanes. The map has been laminated and is distributed to each yacht.” Charlotte has raced in seven VanIsle 360s but only crewed one Swiftsure, on Beyond the Stars. “But,” she said, “I’ve sailed 40 races in my head.”

In the heated contests, race positions are taken extremely seriously and today, Swiftsure’s Sailing Instructions are clear: “The Position reports shall include, in the following order: boat name, sail number, boat’s position, whether inbound or outbound, and the time. Position shall be stated in terms of VTS Map grid square OR latitude and longitude in degrees and minutes. The time and position of each report must be recorded on the boat’s Rounding & Finish Record card.”

The Royal Canadian Navy has added greatly to Swiftsure’s success. Already in 1936, HMCS Armentiersserved as Swiftsure’s committee boat. After the US Coast Guard lightship, Swiftsure, stationed on Swiftsure Bank, retired in 1961, the RCN has supplied a coastal defense vessel as a turning mark on the Bank, as well as a start vessel at Ogden Point each year. And “the People’s Favourite,” HMCSOriole, is the longest-standing Swiftsure race vessel, starting in 1955.

Aboard Oriole near Becher Bay, Lt. Commander Jeff Kibble lost all wind; his crew put down the anchor cinched to 300 feet of chain. “We had a great cook aboard and while relaxing with a delicious beef-and-lamb burger,” said Kibble, “we watched as the whole fleet, shoved back by the flood, retreated toward Race Rocks. Anchored, we kept gaining on them!”

Navigational Tools Our 1930s gentlemen racers would likely be gobsmacked by today’s electronic navigation devices. Being used to paper charts, dead reckoning, a compass, a sextant and blinking lighthouses to determine their position, they’d be amazed by a chart plotter showing the yacht’s exact GPS location, with a radar overlay. They’d fancy the knot meter, wind instruments and depth sounder. AIS would astound them. And the SPOT transponders showing who was where would tickle them no end.

Safety Measures Today’s navigational tools also provide safety measures with radar, VHF and AIS. There’s been one loss-of-life during Swiftsure, when Seattle’s Wilbur Willard, the skipper of Native Dancer,was washed overboard during a knockdown near Carmanah in 1976. The disaster led the Pacific International Yachting Association(PIYA) and Swiftsure to review all safety requirements, including crew competencies.

In the 1930s, racers were obliged to carry a sea-worthy dinghy, lifebelts for all crew, navigation lights, and an anchor light. Today, Swiftsure follows the PIYArequirements which are reviewed annually and establishes “minimum specifications for construction, equipment and accommodations to provide safe and equitable racing.” They distinguish between mono- and multi-hulls and short vs. longer races.

VHF radios andat least one cell phone are prerequisites. Boats must also have a secondary steering mechanism, with crew awareness of steering methods if their boat’s rudder is disabled. Boats must have MOB recording and recovery equipment, and at least two-thirds of the boat’s racing crew must have practiced man overboard procedures annually.

PFDs with leg straps and tethersare required. Jacklines with attachments, life sling, MOB pole, emergency hand-held VHF, current flares and fire extinguishers are onboard necessities. All of these have to be tested and up-to-date.

That said, all the safety equipment is only as good as the materials aboard.

“While Captain of HMCS Oriole, I raced several Swiftsures,” said Gary Davis. “I think Oriolehas the most starts and the least finishes in the annual Swiftsure race. The 2005 Swiftsure was lively with serious winds churning up a big sea. We were doing quite well for the oldest boat participating. It was our normal practice to bundle up the 160 percent doused genoa, stop it every 18 inches and lay it down the port side of the ship with the hanks still on the forestay. That way we could get it up quickly if the winds moderated. The sea built and we were enjoying the vigorous conditions. On a starboard tack, rail down going past Port San Juan, we went through waves that just kept getting bigger. On the biggest wave Oriole plunged burying the foredeck. Because we were heeled over so far, seawater filled the genoa adding about 2,000 pounds of weight on the lee guardrails.

“My sharp Petty Officer Chad Bagnell hollered back to the helm to tack. Tacking is not an instant affair on a ship without winches and organizing a couple of dozen crew to haul sheets. But we tacked. We found the genoa over the side, having broken two stout, solid brass stanchions and bent one. It took the crew about 30 minutes to get the sail back on board, rig a temporary guardrail, and tape up the broken bits.

“We pressed on, but I don’t think we finished that Swiftsure either.”